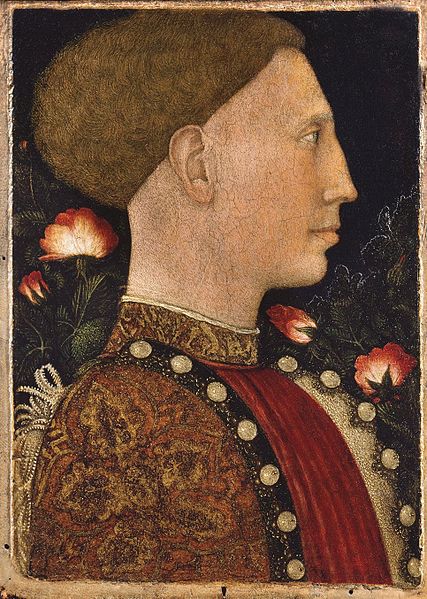

Although he was the illegitimate son of Niccolò III, Leonello deserved the trust of his father, from whom he inherited the leadership of the Marquisate of Ferrara in 1441, succeeding in the few years of his rule in laying the foundations of the Ferrara Renaissance.

Leonello is to be credited with a great political and cultural commitment in favour of his city and the entire territory ruled by the Este family, and his tenacious pursuit of peace was decisive in this.

From the Sant’Anna hospital, the first to be built in Ferrara, to the reopening of the University, not to mention the fortifications and reclamation of various areas, these are just some of the virtuous results of his good government, which unfortunately lasted only ten years due to his premature death at only 43 years of age.

In addition to literary culture, of which we are reminded of his great and much-appreciated oratorical skills, Leonello was attracted to the arts in general, an interest that became one of his great passions as he surrounded himself with works and artists such as Pisanello and Jacopo Bellini, but also Andrea Mantegna, whom he discovered at a very young age.

The life

Leonello was born in Ferrara on 21 September 1407 to Niccolò III d’Este and Stella dei Tolomei dell’Assassino. Despite being an illegitimate child, he was brought up at court following the nobility’s education that included, in addition to the study of letters, military practice: for this reason he was sent to serve under Braccio da Montone, a valiant military captain, returning to Ferrara only after his death some two years later. Returning to the city, he witnessed in May 1425 the death of his older brother Ugo (1405-1425) who, at his father’s orders, was beheaded for treason with his stepmother, Parisina Malatesta, who was also executed. This execution shook the young prince, but he was soon heartened by his father’s new attentions, who, after the death of his eldest son and initiating Meliaduse into an ecclesiastical career, saw Leonello as the most likely successor to the lordship.

After his military education, he took up the study of literature and in December 1429 one of the noblest humanists of the time, Guarino da Verona, settled in Ferrara, becoming the tutor of the young Leonello. The education he imparted to the prince was extensive and included grammar, rhetoric, Latin and Greek. In addition to studying and reading, the master listed long walks in the countryside, hunting, swimming and playing ball among the precepts to be followed: all activities to be carried out in order to find the right balance between intellect and body. The harsh education did however bring tangible results: in September 1433, Emperor Sigismund, who was passing through Ferrara, was welcomed by a Latin oration recited by Leonello: Niccolò III wanted to show his son’s knowledge of the language and culture. Another Latin speech was recited five years later for the reception of Pope Eugene IV at the Council. Leonello’s education lasted about five years, concluding with his marriage (1435), but the friendly and esteemed relations with Guarino lasted a lifetime.

Also in 1429, his father decided to consolidate his bond with the court of Mantua by signing the promise of marriage between his son and Margherita Gonzaga. Her father, however, as a guarantee, wanted Leonello to be legitimised and declared future successor to the leadership of the Marquisate. The marriage was therefore celebrated in February 1435, but lasted only a few years: Margherita died of illness in 1439, leaving orphaned the frail Nicolò born the previous year. Although marriages of the time always implied political expediency, in some cases they were also happy and reinforced by feelings of respect and affection between the consorts. This was the case with Leonello’s first marriage (and also with the second, as we shall see), which adopted various insignia to commemorate the death of his wife: for example, the symbol of the daisy as a clear allusion to her name (of which we find written traces, but no iconographic evidence has come down to us), or a shield with broken lances or arrows (images probably conceived by Guarino).

On 26 December 1441, during a visit to Milan, Niccolò III died suddenly, after having already arranged his succession in his will, in which he named Leonello as his heir, who was able to quietly rise to power on 28 December 1441. The prince only encountered resistance from Niccolò’s widow, Ricciarda di Saluzzo, who claimed for her own legitimate children the possibility of rising to power: however, as she did not encounter any favourable alliances, she abandoned Ferrara the following year. His younger brother Borso, on the other hand, guaranteed Leonello his support during the succession and was instructed to travel to Modena and Reggio to make his citizens swear an oath of loyalty to the new Marquis. Soon Borso became Leonello’s right-hand man, becoming part of the close circle of collaborators who constituted a kind of collegial government. In fact, contrary to the custom of the time, Leonello put himself close to figures who knew how to administer, advise and coexist, including Uguccione Contrari, already a faithful collaborator of his father, Feltrino Boiardo, Giovanni Gualengo and Alberto Pio di Carpi. Leonello’s policy thus moved in continuity with Nicholas III, seeking to adopt a political line that would not expose the flank to the expansionist ambitions of Milan and Venice. The search for peace was in fact the main objective of Leonello’s government, which was able to guarantee a period of tranquillity that favoured the economic and intellectual prosperity of its territories.

Politics

The expansionist aspirations of Milan and Venice, however, often put Leonello in a state of agitation, who in order to protect his own territories found the solution in a possible alliance with Naples. Between 1444 and 1445, Borso was engaged in diplomatic meetings at the court of the King of Naples, Alfonso V of Aragona, to forge an understanding between Naples and Ferrara, presenting the King with the opportunity to seize the Duchy of Milan, since Filippo Maria Visconti had left no male heirs and was debilitated by health problems. To sanction this unusual coalition was, as was always the case, celebrated by marriage: in 1444 Leonello married in second marriage Maria of Aragona, natural daughter of the King of Naples. For this occasion, Pisanello forged a medal with the effigy of Leonello (the last of the six medals dedicated to him by the artist), on the reverse side of which was depicted a lion tamed by Love, showing him a musical sheet, with an eagle in the background. Unfortunately, even this marriage union was not destined to last, as Maria died in 1449.

Political designs and alliances changed quickly and King Alfonso, known as the Magnanimous, used this new union to enter into a further alliance with the Visconti and the Papal States, in order to hinder Francesco Sforza’s rise to power. It was precisely the conflict in the lands of Romagna between the latter and Sigismondo Malatesta that reopened the war in 1445. The imminence of a conflict on his territories convinced Leonello to take a more cautious attitude and distance himself from all those forces that were too powerful for his state, leading him once again to confront the neighbouring court of Mantua. At such a delicate moment, Leonello undertook several diplomatic missions, succeeding in reconciling the parties and proving to be a valid mediator. The situation, about to be resolved, however, precipitated with the death of Filippo Maria Visconti in August 1447: Leonello tried to take possession of some territories, but, having obtained Scrivia and the offer of Pavia, soon realised the power of Ludovico Sforza and agreed to become an ally alongside Venice. The marriage between his son Niccolò d’Este and Ippolita, Sforza’s natural daughter, was celebrated to seal the agreement. Before the final establishment of Ludovico Sforza in 1450, Leonello rejected the possibility of taking over Parma and Piacenza, partly on the advice of the Serenissima, who was worried about the possibility of further tensions and wars. Leonello therefore returned to a less dynamic policy and spent himself in Venetian-Napolitan agreements.

In 1447, the equestrian sculpture that the Council of the Savi of Ferrara (and Leonello) wanted to erect in honour of Nicholas III was finished. It was placed in 1451 next to the Horse’s Face (the one that can be admired today in Piazza Municipio is an early 20th century copy, as the original was destroyed by the Jacobins during the French revolution). A competition was announced for the creation of the statue, to which two Florentine sculptors submitted: Leon Battista Alberti was called to judge the best, but since not even the Council was able to decide the winner, it was decided that Antonio di Cristoforo should make the statue of Niccolò III and Niccolò di Giovanni the Horse. It should be noted that this was the first equestrian statue executed after that of Teodorico in Ravenna.

Leonello died at the age of only 43, on 10 October 1450 in the palace of Belriguardo, due to an untreated abscess on his head.

It was during the last year of his life that an object of extraordinary beauty entered Leonello’s collections: the so-called ‘Reliquary of Montalto’, which came from the French royal collections and is now in the Sistine Museums of Piceno, in the Bishop’s Museum of Montalto. The precious gold and silver reliquary, decorated with enamels en ronde-bosse, precious stones and an ancient cameo, was made in France probably in Paris at the end of the 14th century. On its surface, the iconographic cycle of the Passion is narrated: in the centre, a cross made of coloured stones and pearls forms the background to an angel with large blue and white outstretched wings holding the dead Christ. On the sides, in two circular spaces, are depicted the Flagellation and the Crucifixion, while at the top is God the Father surrounded by angels and, at the bottom, the Deposition in the sarcophagus.

Activities in favour of the Marquisate

Leonello, in his 10 years of rule, devoted himself with great energy to improving the conditions of his people, both from the point of view of politics and economics, and from the higher level of culture. The works carried out by Leonello were in fact aimed at achieving, as Prince, glory and good government through culture, protection granted to erudite men and artists, clemency and understanding towards his people.

In architecture, he was able to reconcile the ideal of beauty with the usefulness of constructing and improving already existing buildings with a defensive function. From 1445 to 1449, he equipped Lugo with a fortress, fortified the tower of Bagnacavallo, built the walls of the city of Rubiera and completed the construction of the Rocca di Finale, a work begun by his father. Some of the most beautiful palaces such as Belriguardo, Migliarino and Copparo were enlarged and enriched.

In 1444, in agreement with the bishop of Ferrara, the blessed Giovanni Tavelli da Tossignano, Leonello worked on the construction of the city’s first hospital, Sant’Anna, in favour of the less fortunate: an old Augustinian convent near the Estense Castle, founded in the early 14th century by the Franciscans, was redeveloped by the architect Pietrobono Brasavola and already in 1445 it housed the first needy.

Leonello was also involved in the construction of embankments to prevent flooding of the river, as well as in the reclamation of marshy and non-cultivable areas. These works were undertaken in favour of the farmers, for whom tax relief was also introduced to protect agricultural activity and encourage the cultivation of the new fertile areas. In addition, Leonello supported the cleaning of the city, including the cleaning of streets, wells and public cisterns.

Leonello, through a liberal and enlightened policy, also gave new impetus to commercial trade, supporting Jewish communities and Venetian merchants. Industries were also stimulated through the exemption of taxes and the acquisition of privileges for certain categories that Ferrara needed, such as masters for working lead, tin and gold, masters of armour, Flemish tapestry workers.

Great impulse had the art of coin engraving. At that time, medals were no longer engraved, but were executed by casting: this innovation brought an easing in the workmanship that could also be carried out by painters, such as the six medals executed for Leonello by Pisanello between 1441 and 1444. The medals, on the recto, bore the face of the marquis, while on the verso an emblematic representation full of political meanings and allusions to the virtues: a representation of Prudence (the head with three faces ideally past, present, future), of Peace, an allegory of Temperance, one of Impartiality and, the largest and perhaps the most important, the one executed for Leonello’s second wedding, mentioned above.

Leonello was also an ardent promoter of culture: to him we owe the reopening of the University of Ferrara (probably closed since 1402), the growth of which he stimulated through the arrival of new and authoritative professors capable of attracting students, including foreign ones, such as Greeks, French, Germans, English, Hungarians and Poles. In these and the following years, the Ferrara Studio became one of the most florid in Italy.

The Estense library, established by Nicholas III, also became one of the first in Italy in terms of the richness and rarity of its codices. The library’s inventory, dated 1436, lists 279 volumes ranging from classical authors to contemporaries such as Petrarch and Boccaccio. Leonello saw the library as an instrument of culture and therefore sponsored numerous acquisitions and entrusted the copyist Biagio Bosoni with the circulation of texts. His sensitivity is evident in the careful indications he provided for the correct preservation and enjoyment of books: for example, he indicated how to preserve volumes from dust and gave ‘recipes’ to keep pests away.

The Life-long friendship between Leonello and the great humanist Leon Battista Alberti should be remembered, who dedicated some of his works to him, declaring that the treatise De Re Aedificatoria, was written at the invitation and encouragement of the Marquis himself.

The painters at Leonello’s court

We know that Leonello surrounded himself with many painters and in his short reign laid the foundations for the artistic renaissance flourishing in Ferrara: this prosperous moment for the arts was made possible by the years of peace that Leonello was able to maintain in his territories.

Antonio di Puccio Pisano known as Pisanello (c. 1395-1450) was one of the most illustrious painters at the Este court. The artist came to Ferrara to meet his friend Guarino da Verona who introduced him to Leonello in 1432. The Marquis was enthusiastic about his painting and immediately commissioned a painting of the Virgin, from which their long artistic relationship began. Visits to Ferrara were frequent and their shared passion for ancient art led to the creation of the new image of the prince, inspired by the effigies of ancient emperors found on Roman coins. The profile created by the artist characterises the image of Leonello that can still be admired today on the seven medals designed by Pisanello between 1441 and 1444. This is the origin of the famous face of the Marquis portrayed in profile, currently preserved at the Carrara Academy in Bergamo.

In the ‘Vision of St. Anthony and St. George’ (or ‘Virgin with Child and Saints’), housed in the National Gallery in London, critics have likened the figure of the warrior-saint to a probable portrait of Leonello: it is possible to discern a certain resemblance to the patron in the profile and hair.

Jacopo Bellini (c. 1400-1470) arrived in Ferrara in 1441, when Pisanello had already been working on the portrait of Leonello for several months, and he too wanted to try his hand at this subject: according to the chronicles of the time, he was proclaimed the best of the two, but unfortunately the painting has not survived. However, it is possible to admire the ‘Madonna of Humility’ at the Musée du Louvre, a small devotional panel where Leonello is depicted kneeling in prayer before the Virgin and always in profile; note the very elegant purple and gold damask mantle.

Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) was one of the greatest artistic talents discovered by Leonello. He was called upon at a very young age, in 1449, to paint a panel showing the portrait of the Marquis on one side and that of his favourite Folco di Villafora on the other, which has now been lost.

In the same year, the Flemish artist Rogier Van der Weyden (1400-1464) arrived in Ferrara, from whom Leonello bought a triptych and to whom he commissioned other works, which unfortunately arrived late in the Este city after his death. The portrait of his legitimate son Francesco d’Este (now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York) is a work by this artist.

Angelo Maccagnino (news from 1439 to 1456), a painter of Sienese origin, was appointed court painter from 1447 and his name is linked to the decoration of the Studiolo di Belfiore, where he painted some of the Muses. After Leonello’s death, he passed into the service of Borso.

The Studiolo of Belfiore

Leonello conceived a space for study and contemplation in the Delizia di Belfiore, on which numerous artists worked. It was himself who conceptualised the decoration with the theme of the Muses and, having presented the idea to Guarino da Verona, met with his approval. The Muses have ancient roots that go back to Greek mythology in which they were divinities born from the union between Zeus and the Goddess of memory: they represented the ideal of artistic inspiration and, more generally, of intellectual activities, to the point of becoming, over time, protectors of all human wisdom. The Studiolo was a private space for the lord, where he could enjoy intellectual activities and a place for confidential conversations. In a space so full of virtues, which the prince himself was called upon to impersonate, the theme of the Muses was particularly appropriate. It was then Guarino who characterised the iconography of the nine Muses, protectors of the arts: in his letter to Leonello, dated 5 November 1447, the humanist indicates how many and which Muses are to be depicted, providing for each the role, characteristics and iconographic attributes. In this space, the Muses have these characteristics: Clio is the inventor of history, Thalia of agriculture, Erato takes care of conjugal bonds, Euterpe creator and teacher of the flutes, Melpomene of singing, Terpsichore of dancing, Polyhymnia oversees the cultivation of the fields, Urania of astronomy and finally Calliope the explorer of science and priestess of poetics.

On the occasion of the reopening of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Ferrara with the exhibition-dossier “Cantieri Paralleli. Lo Studiolo di Belfiore e la Bibbia di Borso 1447-1463” the Estensi Galleries, National Art Gallery of Ferrara in collaboration with FrameLAB, Department of Cultural Heritage – Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna have launched a study and multimedia project on the Belfiore Studiolo.

The paintings were commissioned to Angelo Maccagnino and, after his death, to Cosmè Tura: critics are unanimous in identifying the hand of Hungarian painter Michele Pannonio even though no documents have been found to prove this. In addition to the pictorial cycle dedicated to the Muses, the walls of the Studiolo were finished with precious woods with inlaid panels by Arduino da Baiso and the brothers Cristoforo and Lorenzo da Lendinara, known as the Canozi, but nothing has come down to us. The decoration of the studiolo began in January 1448.

Only 6 of the 9 Muses have come down to us and are dispersed in various European collections: in Italy at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara (Erato and Urania) and at the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan (Tersicore), at the Staatliche Museen Gemäldegalerie in Berlin ( Polimnia), at the National Gallery in London (Calliope) and in Budapest at the Szépművészeti Múzeum ( Talia). In the collections of the latter museum there are two other Muses, Melpomene and Euterpe, but their attribution to this cycle is still not very credible.

Here is a digital reconstruction of the Studiolo.

https://patrimonioculturale.unibo.it/studiolodibelfiore/Studiolo%20di%20Belfiore.html

After Leonello’s death in 1450, the decoration of the Studiolo was completed in the following years by Borso, who made some changes to the narrative layout.

Angelo Maccagnino, Erato,http://www.gallerie-estensi.beniculturali.it/ricerca-avanzata/id/52818, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9498603

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Pardi “Leonello d’Este, marquis of Ferrara”, Ed. Zanichelli, 1904;

Toffanello “Ferrara: gli Este 1393-1535” in “Corti italiane del Rinascimento. Arti, cultura, politica, 1395-1530” edited by M. Folin, Ed. Officina Libraria, 2010;

“La corte di Ferrara” in “Gli Estensi”, Ed. Il Bulino, 1997;

Luciano Chiappini “Gli Estensi: mille anni di storia”, Ferrara: Corbo, 2001;

“Le Muse e il Principe Arte di corte nel Rinascimento padano” edited by A. Di Lorenzo, A. Mottola Molfino, M. Natale and A. Zanni (essays and exhibition catalogue) Ed. Franco Cosimo Panini, 1991;

Manni “Belfiore Lo studiolo intarsia di Leonello d’Este (1448-1453), Ed. Artioli Editore, 2006;

Torboli “Diamante! Curiosità araldiche nell’arte estense del Quattrocento”, Ed. Cartografica, 2010;

Cavicchi “La musica nello studiolo di Leonello d’Este” in “Prospettive di iconografia musicale” edited by Nicoletta Guidobaldi, 2007, Ed. Associazione culturale Mimesis. Talks at the study days “Le immagini della musica. Themes and issues of musical iconography” October 2004;

Treccani, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Italians.