Ercole I, son of Niccolò III and brother of Leonello and Borso, was one of the longest reigning rulers of the House of Este (34 years of rule), thanks mainly to his strong diplomatic skills and aversion to war. This tendency was greatly influenced by the wound he suffered as a young man in battle that rendered him lame, and the stinging defeat with Venice, the only war in which he was involved as a duke.

In such a long period of peace, the city of Ferrara developed enormously, expanding its territory until it doubled in size and giving space, in parallel, to the arts and culture, in particular theatre and music, true passions for Ercole I, which found very fertile ground in this period. In fact, the Este court became one of the most refined in Europe, thanks also to the famous theatrical performances capable of attracting the high aristocracy of the peninsula to Ferrara, while in the field of music, it even competed with the Pontifical Sistine Chapel. Gifts of diplomacy and culture were passed on to his numerous sons, who were to become central figures of the Italian Renaissance and important ‘pawns’ in the chessboard of alliances.

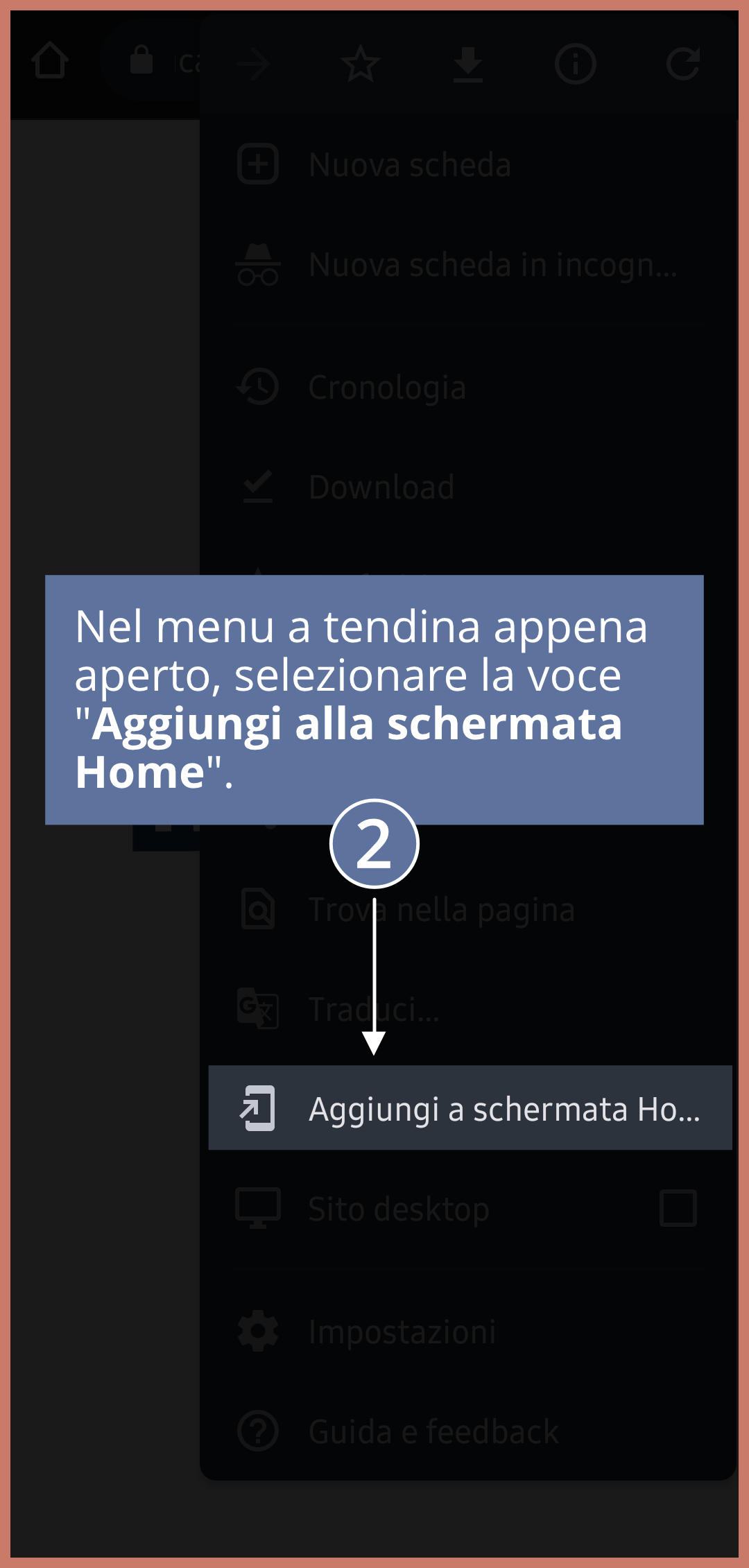

Neapolitan upbringing

Ercole was born in Ferrara on 24 October 1431 to Niccolò III (who was 48 years old at the time) and Ricciarda da Saluzzo, married on his third marriage, and is therefore half-brother to Leonello and Borso born of the union with Stella dei Tolomei dell’Assassino.

Not much is known about his childhood, but it is certain that following Leonello’s rise to power, Ercole and his younger brother Sigismondo were sent to live at the Neapolitan court of King Alfonso I (Leonello’s father-in-law at the time), also to avoid possible problems regarding the legitimacy of the succession. Here they grew up together with Ferrante, the King’s natural son, receiving an appropriate military and chivalric education. In this context, Ercole found himself involved in a resounding about-turn, desired by Borso, who in the meantime had risen to power on the death of his brother Leonello: he was ordered to go into the service of John of Anjou, Duke of Calabria and pretender to the throne of Naples. He practically found himself fighting against the Aragonese king who had welcomed him at Court. This betrayal led to years of diplomatic crisis with Naples, which was only smoothed out thanks to intense ambassadorial work, until a new Aragonese-Estense alliance was formed, confirmed in 1472 with the marriage between Ercole and Eleonora of Aragona.

The return to Ferrara and the incident in battle

In 1463 Ercole and Sigismondo returned to Ferrara as governors of Modena and Reggio respectively. It was during this period that Ercole fought alongside the Venetians in support of the anti-Medicean actions that were taking place. It was precisely in the battle of Molinella (near Bologna) in July 1467 that Ercole, in order to save Bartolomeo Colleoni (a military leader enlisted by Venice) who was by then overwhelmed by the Medici army led by Federico da Montefeltro, was seriously wounded in the foot by a firearm shot, which made him lame and earned him the nickname ‘ciotto’ (little stone). This episode was made famous thanks to Ariosto’s verses in Orlando Furioso (III, 46):

Ercole or vien, ch’al suo vicin rinfaccia,

col piè mezzo arso e con quei debol passi,

come a Budrio, col petto e con la faccia

il campo volto in fuga gli fermassi;

non perché in premio poi guerra gli faccia,

né, per cacciarlo, fin nel Barco passi.

Questo è il signor, di cui non so esplicarme

se fia maggior la gloria o in pace o in arme.

The Pio Conspiracy

In 1469, he was instead offered to take part in a plot against Borso, planned by Gian Ludovico Pio, Piero de’ Medici and Galeazzo Maria Sforza, the so-called ‘Pio Conspiracy’. However, Ercole did not allow himself to be tempted by promises of territory and reported the fact to the Duke, who had the conspirators arrested. The loyalty shown by Ercole was rewarded with his participation in the Secret Council alongside Borso. While his loyal behaviour gained him new esteem internally at court, externally it left him with few allies capable of supporting him during a succession crisis, which happened the following year when Borso’s health worsened precipitously in the summer of 1471. Ercole still managed to obtain the title, but not without problems. The rivalry with Niccolò, Leonello’s son and possible successor, was long and harsh, so much so that there was even an attempt to poison Niccolò, a guest at the court of Mantua, by one of Ercole’s loyalists. The situation did not change even after the investiture of Ercole was renewed by Pope Sixtus IV (born Francesco della Rovere). The end came only in 1476, with Niccolò’s attempted coup d’état and his beheading.

1472, the first year as Duke

The year 1472 marked a change in the political orientation of the Duchy: Ercole moved away from the Venetian Republic and moved closer to the Kingdom of Naples, putting an end, thanks to his marriage, to the rancour born with his youthful betrayal (in any case imposed on him by Borso) against King Alfonso. The agreement was thus concluded to marry Eleonora of Aragona, daughter of Ferrante, Ercole’s childhood friend who became king under the name of Ferdinando I, who proved to be a wise and loyal woman.

The wedding took place on 1 November 1472 and it was not until May of the following year that Ercole’s brother, Sigismondo, travelled to Naples to accompany the bride to Ferrara and to conclude negotiations regarding the bride’s dowry. In early July Eleonora reached her new city, which welcomed her with a week of great festivities, including tournaments and banquets, in honour of the new union. The couple had numerous children and some of them became some of the most important figures of the Renaissance: in May 1474 the first daughter Isabella, future Marchioness of Mantua, was born, followed in June 1475 by Beatrice, future wife of Lodovico Sforza and Duchess of Milan, and finally in July 1476 the long-awaited male child, Alfonso, who would succeed his father Ercole as Duke. Four more sons followed: Ferrante, Ippolito, who was to become a powerful Cardinal, Sigismondo and Alberto. In the same year, upon payment of the annual fee of 7,000 florins, Ercole obtained from Pope Sixtus IV the renewal of the ducal title over Ferrara for himself, his children and his legitimate and natural grandchildren in the direct line up to the third generation, thus legitimising his rule. It was on this occasion that he was granted the privilege of including the two papal keys in the Este coat of arms.

Less than a year after his rise to power, Ercole also laid the foundations of the intense building activity that would change the face of Ferrara, making it ‘the most modern city in Europe’. It was in 1472 that work began on the renovation and embellishment of the existing buildings on the piazza and the creation of the ‘Barco’, an enormous green space, north of the castle, largely unbuilt and enclosed by a walled enclosure. It contained a bovine and equine farm, land cultivated with legumes, cereals and vineyards and a fishpond for the needs of the court. Hunting, which could take place here due to the presence of many animal species such as hares, deer and wild boar, was strictly reserved for the Duke and his most important guests. This huge ‘enclosure’ was also home to the Duke’s falconry.

The coup attempt

Niccolò, as mentioned, did not easily give up the idea that he could not take possession of the Duchy and, probably supported by Ludovico Gonzaga, attempted a coup d’état in September 1476. Taking advantage of Ercole’s momentary move to Belriguardo, Niccolò let a large group of armed supporters, hidden inside boats, enter the city from Mantua via the river Po. Exploiting a gap in the city walls, they entered the square and freed the prisoners locked up in the Palazzo della Ragione, while Niccolò urged the citizens to rebel in the hope of finding their support to rise against Ercole’s power. Instead, the reaction was the opposite: the population fled in fear and did not support Niccolò, giving the Duke time and opportunity to learn of the conspiracy. Ercole therefore decided to retreat to Lugo, which was well fortified, recalling his troops. Meanwhile in Ferrara, Ercole’s brothers were involved in the resistance, first managing to drive out the group of rioters and then to capture them near Bondeno. Ercole’s revenge was rapid and without recourse: numerous were the punishments including exile and confiscation of property, many also the death sentences by hanging, while his nephew Niccolò was ‘granted’ decapitation. As a member of the House of Este, Niccolò’s remains were given honourable treatment, with a sumptuous state funeral at which his body was reassembled and burial in the Church of San Francesco, in the red ark of the Este family. Thus ended the internal struggle for succession within the Duchy.

The ‘Salt War’ (1482-1484) with Venice

Having resolved the internal dissensions within the Duchy, Ercole began to suspect that Venice had helped Niccolò in the conspiracy and had made peace agreements with the Papal States. Thus Ferrara became closer to the policies of Naples and Florence, which, together with Milan and Mantua, were allied in the war waged against the Papacy. Many tensions had so far fuelled the animosity between Venice and the Duchy, including the Este’s extraction of salt at Comacchio, but war broke out when Sixtus IV agreed to the Serenissima’s demands to acquire Ferrara in exchange for its help against the King of Naples. Venice had actually already secretly deliberated war against Ferrara, but was only waiting for the Pope’s decision and legitimisation, so it had the advantage of having already prepared the war instruments for immediate action and also found the necessary money.

Ercole’s defensive line was not effectively prepared, entrusting the fortresses of Stellata and Bondeno alone with its defence. The power of Venice and its allies was unstoppable: in a short space of time, they took over the entire Polesine and Ercole was thus forced to call the allies to the rescue.

The war years, already difficult due to the huge military expenditure and devastation in the territory, were made even more difficult by the plague and famine that hit Ferrara and not least by the illness of the Duke himself. In such a delicate moment, the factions hostile to Ercole became stronger, but Duchess Eleonora was able to hold on to power by asking for a further effort from the population, who once again demonstrated their attachment to the House of Este, going so far as to parade in front of the infirm Duke as a sign of support.

The Venetian troops managed to penetrate the Barco and the Delizia di Belfiore, also committing acts of violence and raids on nearby ecclesiastical buildings. After almost three weeks of siege, the Pontiff finally signed peace with Naples on 12 December 1482. In spite of this, Venice’s hostilities against Ferrara continued and in March 1483 a very serious event occurred: the Venetian militia reached as far as the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli where the statue of Marquess Nicolò was torn down and stolen, and promptly sent to the lagoon city as a trophy. But the greatest wound for Ercole would come later, with the peace of Bagnolo, signed with Naples and Milan in August 1484, which sanctioned the loss of the Polesine of Rovigo, whose territories passed under Venetian control to the damage of the Duchy of Ferrara.

Neutrality as a political strategy

Ercole was greatly upset by the loss of those territories, but what infuriated him most was the ease with which the allies disposed of his possessions during the negotiation of the surrender. For this reason, he decided not to take any further interest in such far-reaching political issues, choosing more convenient positions of neutrality for his small state.

In the following years, even on the occasion of the descent of Charles VIII and the French army in 1494, Ercole in fact maintained a mediating role between the French and the Italian states, trying not to explicitly participate in the conflicts. His pro-French policy was nevertheless evident, but thanks to tenacious diplomacy and wait-and-see manner he managed to maintain his neutrality. The same neutrality that earned him protection from the French after the descent of Louis XIII at the end of the century.

The Duke pursued his policy of peace by making alliances with the most powerful Italian states and, as was always the case, the easiest and most effective way was marriage. Ercole’s numerous children thus became strategic ‘pawns’ moved on the chessboard of alliances: Alfonso married Anna Maria Sforza (1491), daughter of the Duke of Milan, in the first marriage and Lucrezia Borgia (1501), daughter of Pope Alexander VI, in the second; Isabella married Francesco Gonzaga, future Marquess of Mantua (1490) and Beatrice married Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan (1491). Their son Ippolito was initiated into an ecclesiastical career, which quickly and brilliantly led him to become a Cardinal in 1493, thus increasing the prestige of the family and the political relevance of the Estense State. In the same year, however, Eleonora, Ercole’s wife and valuable advisor, died.

After the alliances created through the conjugal bonds of his children, Ercole was able to look to the future of his government with greater tranquillity, directing his forces towards the territorial expansion of Ferrara.

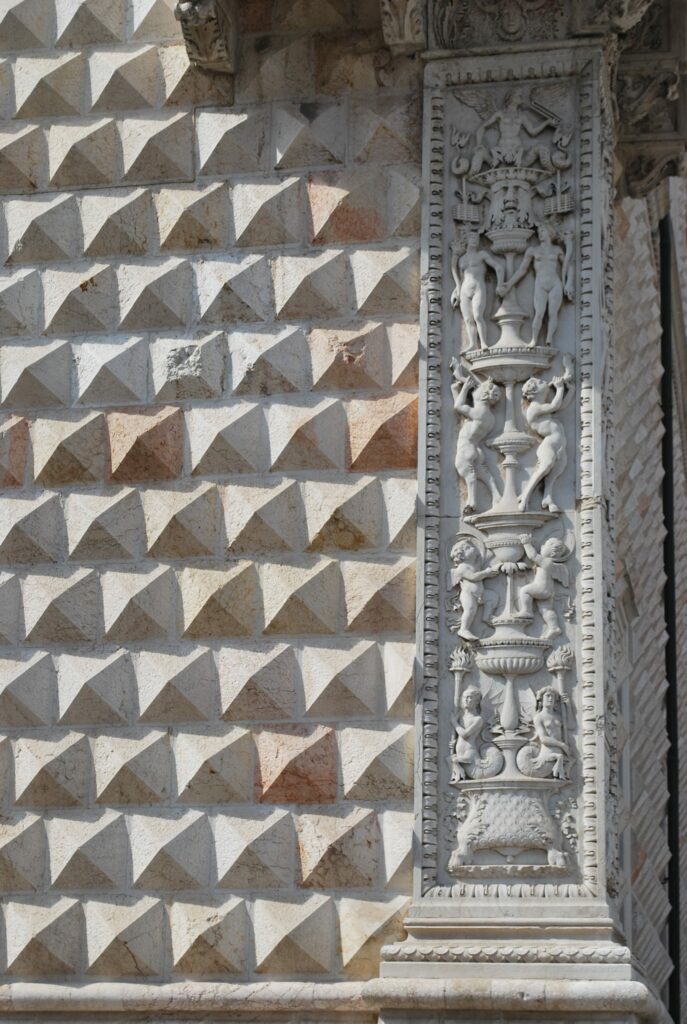

The ‘Erculea’ addition and the ingenuity of Biagio Rossetti

The Duke’s desire to expand the city and build the ‘Terra Nuova’ (New Land) was a bold and innovative project that could not have been realised without the work of a large group of architects and planners who, alongside Ercole, knew how to imagine and shape the city. Prominent among them was Biagio Rossetti, who in synergy with other figures including Battista and Antonio Maria di Rainaldo, Bartolomeo Tristano and Antenore da Bondeno, gave life to no less than 20 civil and 12 religious building sites in a decade. The coordination and supervision of these factories was entrusted to the Ufficio delle Fabbriche e delle Munizioni Ducali, whose head was Biagio Rossetti.

The desire to enlarge the city’s space had many reasons, starting with a defensive one: the war of 1482 had shown the fragility of the Este defence against Venice, and the incursions and violence in the Barco and in the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli had made changes urgent. Obviously, the start of the works promptly alerted the Venetians, who thought it might be an operation in anticipation of a new war, but Ercole repeatedly affirmed his peaceful intentions: the population was growing and new spaces were needed. But there is also another reason, an economic one: Ercole would have bought the best and most extensive land, and would then have been able to make a considerable profit.

It must be remembered that in Ferrara the term ‘addizione’ was already known and indicated the annexation of surrounding land within the walls. Before this there had already been at least two: the one approved by Niccolò (after 1386) and the one by Borso (from 1451, already set by Leonello). The addition commissioned by Ercole also fits into this line, differing from the previous ones in the vastness of the land included, about 250 hectares, and the length of the new city walls, at least 6 kilometres.

The city doubled in size and the work lasted about twelve years, between 1492 and 1505 (the year Ercole I died). The huge expenses incurred by the ducal coffers caused taxes to rise sharply and a large number of farmers were forced to work in corvées far beyond what was customary. This created strong discontent among part of the population. But dissatisfaction also came from the new road layout of straight and wide roads with an unusual appearance, which did not meet with the taste of the citizens and especially of the landowners, who saw their plots of land cut up into uncomfortable portions. Part of the city’s aristocracy, instead, enthusiastically adhered to the Duke’s enterprise and took advantage of it by building new elegant palazzi, including: palazzo Prosperi-Sacrati (already Da Castello), da Trotti-Mosti, Strozzi-Bevilacqua, palazzo dei Diamanti, built for Sigismondo, the Duke’s brother, and that of Giulio d’Este, his illegitimate son. These palaces are located near what was planned as the heart of the Addizione, namely the ‘Piazza Nova’ (today Piazza Ariostea), conceived as a new gathering space that, according to the plan, was to have a marble column with an equestrian statue of the Duke at its centre (which was never realised, however).

The Delizia di Belfiore and the Certosa palace were also located within the new city walls. In addition to the grandiose palaces, Ercole patronised the construction in the Terra Nuova of numerous modestly sized residences referred to in the sources as ‘casette’ (small houses) built on one or two floors and made of brick. Built at the Duke’s expense for a lower-middle class, they were distributed in various ways (gift, sale, rent, symbolic fee) to pay off debts or to reward old service loyalties.

The operational phases of the Addizione Erculea followed different stages: initially the great perimeter moat, over 30 metres wide, was excavated, then came the draining of the marshy ground and the building of a road profile already established made up of towers and three new gates at the end of the main road axes (Porta Po, Porta Mare and Porta degli Angeli). Finally, connecting curtain walls were built (low and scarped) while the inner perimeter of the enclosure rested entirely on embankments. The enclosure still included round towers, which would later be transformed into more up-to-date forms, but the ‘puntone’ and the ‘baluardo’ or ‘bastion’ were also introduced. Even today, within the enclosure, between the Certosa and the Jewish Cemetery, there are four hectares dedicated to agriculture, a unique case in Italy of land cultivation within the city walls.

The paternity of the Addizione Erculea is still a much debated issue. According to the most recent studies, the project was planned at the request of the Duke, but its realisation was made possible by the united efforts of a multitude of professionals who worked on it jointly, but with ample autonomy. Biagio Rossetti, remains a leading figure in the project, both for the primary role he played as head of the Office of the Ducal Factories and Munitions, in charge of coordinating, controlling and approving all the construction sites opened in the city, and as the contractor of some of the most important works (the walls, Piazza Nova, Palazzo Costabili and dei Diamanti to name but a few).

Religious fervour and the ‘Living Saint’

Duke Ercole lived the last years of his life with great religious fervour. In the Terra Nuova he founded five new convents: Santa Maria della Consolazione, Santa Maria delle Grazie, those of San Rocco and San Giovanni Battista and finally the monastery of Santa Caterina da Siena. The latter was erected in little more than two years to house Lucia Broccadelli da Narni (1476-1544), the ‘living Saint’ protagonist of a strong popular and aristocratic devotion and a ‘kidnapping’. The Dominican, after a childhood of celestial visions, received the stigmata and in these Ercole recognised the symbol of her holiness. Thus began negotiations with the Pope to obtain permission to take her from Viterbo to Ferrara, with the promise to build a monastery there, of which she would become abbess. But Viterbo did not want to give up its ‘Saint’, so Lucia was forced to leave the city at night, hidden among baskets of laundry. Some documents preserved in the State Archives of Modena and recently brought to light by Marco Folin, would reveal the falsity of Sister Lucia’s stigmata and, if so, behind Ercole’s request there may have been his desire to attract pilgrims to Ferrara to increase the city’s prestige. Indeed, with the death of the duke, Lucia was stripped of all privileges, destining her to the last place in the hierarchy of the monastery, where she remained until her death.

But the religious fervour attributed to Ercole cannot be diminished by this episode: the Duke was very involved in religious constructions, both in the foundation of new buildings and in the restoration or reconstruction of already existing churches or monasteries. Singular is the double intervention on Santa Maria degli Angeli, rebuilt the first time following the violence perpetrated by Venetian troops, the second time in 1501 following the passage of a comet star: the vision of the star occurred during a visit by Ercole, who interpreted this sign as the Lord’s will to build a larger and more magnificent church there. Work began immediately, but on the death of the Duke (1505) the church, which was in any case already officiating, was not completed.

Succession

In the last years of his life, Ercole, although tired and frail, continued to travel, driven above all by his ardent religious faith. The duke, also in view of the succession, was worried about the strong rivalry between his sons Alfonso and Ippolito, which in some episodes led to quarrels and violence by soldiers of the opposing and reciprocal factions.

Ercole’s last wish was to call to his bedside the musician Vincenzo da Modena, who cheered his last hours by playing the harpsichord for him. In a silent Ferrara covered by a thick blanket of snow, Ercole died on 25 January 1505.

The situation regarding the succession did not bode well for a peaceful resolution between the two brothers, but against all expectations Alfonso and Ippolito quickly came to a peaceful agreement and Alfonso succeeded his father without any disruption, on the same day of his death, while Ippolito became his brother’s arm.

Theatre and music

Ercole had a particular interest in theatre, entertainment and music, so much so that the court of Ferrara, at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, was par excellence the place of invention and experimentation of Renaissance theatre. It must be remembered that at that time Ferrara was at the height of its magnificence, able to compete with the largest and richest courts. Many factors concurred to make Ferrara a truly ‘European city’: from Leonello onwards, Ferrara had been culturally enriched with the reopening of the Studio and the teaching of illustrious professors specially called to teach there; the high literary education reserved for the Este princes; the creation of a large and organised court library; the circulation of texts; the work of intellectuals, artists and painters involved in daring decorative cycles (Schifanoia, the Studiolo, Borso’s Bible, Hercules’ Breviary, etc….). All these activities created a cultural fabric of the highest level.

Theatrical activity was characterised by a wealth of performances, ranging from fabulae in the vernacular to sacred plays, such as the Passions in the piazza or in the cathedral. To these were added courtly festivities such as jousts, triumphal entrances, secular or religious festivals (weddings, baptisms, funerals). Traditionally, reference is made to Plautus’ Menaechmi as the first performance, which took place in the courtyard of the Ducal Palace on 25 January 1486, an event within the Carnival, which was followed the following year by the staging of Amphitryon. The great success led to an increase in the number of performances that were staged in series from 1491 onwards: three between 1491 and 1499, four in 1500 and 1503, and even five in 1502. The period between 1491 and 1499 saw a smaller number of performances, as a mark of respect after the death of his wife Eleonora (1493). In 1504, the Duke felt the need to build a more stable space for performances and started work on the ‘Sala delle Commedie’, which unfortunately remained incomplete due to Ercole’s death and his successor’s desire not to continue with the project. It is however to be remembered as one of the first Renaissance attempts to create a permanent theatre, and it is likely that in the planning stage, Pellegrino Prisciani’s work ‘De Spectacula’ on Roman theatres was a source of study and inspiration.

The popularity and enthusiasm for comedies, which were also open to large sections of the population, led Francesco Gonzaga and Ludovico Sforza to ask Ercole to lend them scripts to be staged at their courts.

The performances, however, also required a great economic effort for the state treasury, just think of how many people and workers were employed: the literati who translated the texts, carpenters and sculptors for the creation of the sets, painters for their decoration, costume designers for the creation of the costumes and musicians for the preparation of the musical and dance interludes. The audience could be estimated in the thousands and among them was the entire aristocracy of northern Italy, demonstrating the importance, political prominence and power they represented.

We can mention two great figures involved in this activity so dear to the Duke: Ludovico Ariosto and Biagio Rossetti. The former began his activity as Court writer under the rule of Ercole, in his early twenties. His father, Niccolò Ariosto, was already working for the Duke as garrison commander and then as general treasurer of the troops, finally as head of the municipal administration. The young Ludovico was hired by Ercole as a court stipendiary in 1498 and was responsible for writing plays and staging performances for him. The other important figure was Biagio Rossetti, ducal engineer from 1483, years when theatre was in full ferment. In addition to dedicating himself to the construction of civil and military buildings, Rossetti had to supervise the decoration of buildings and the construction of the city’s festive apparatus for special ceremonies and performances.

Ercole’s other passion was music, cultivated since his childhood at the court of Naples, for which he acted as a true patron, calling the most important musicians of the time to the court and favouring players and composers. The Duke went so far as to establish one of the most important music chapels of the time, which ranged from ordinary religious services to sacred dramas to secular chamber singing. Probably the highest achievement of Ercole was the collaboration of an international chapel master, the famous Josquin Desprez, who signed the famous Missa ‘Hercules Dux Ferrariae’. At that time, Ferrara also became one of the most important centres for the performance of viola music.

The ‘Breviarium Romanum’

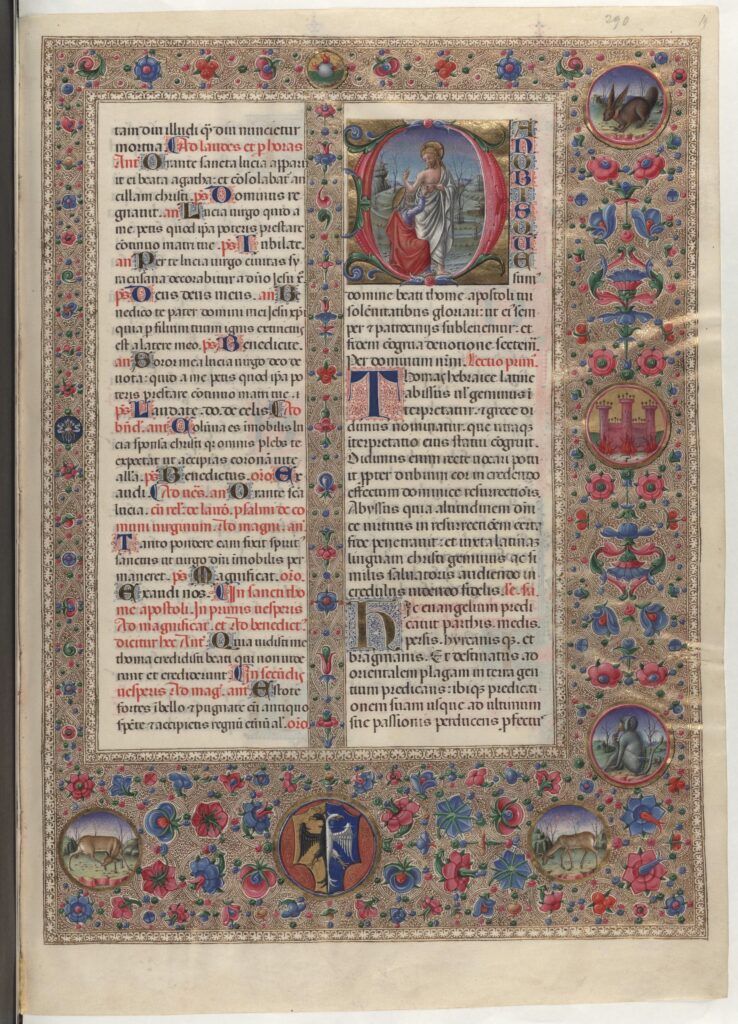

In continuity with the legacy left by Borso with his “Bible”, the second Duke also wished to leave a precious testimony of beauty and power with the commission of the “Breviarium Romanum”, today known as the “Breviary of Ercole I”, returned to the Biblioteca Estense in Modena in 1939 after the Austrian interlude. Unfortunately, during its stay in Vienna, four miniated pages were removed, which are now preserved in Zagreb at the “Strossmayer Gallerija” (where some of the most beautiful miniated pages of another Estense codex, the “Offiziolo Alfonsino”, can also be found).

The codex, produced between 1502 and 1504, is the fruit of the maturity of the Ferrara miniature in which the elements of the Lombard and Flemish tradition are already integrated. It consists of 491 sheets, 45 of which are full-page illustrated. The text is rich in decorations, figured initials and saints, roundels with animals, phytomorphic motifs and, of course, the heraldic symbols and emblems of the Duke to which, as already happened with the ‘Bible of Borso’, in some cases those of his son and future successor Alfonso I will be overlapped. The artists who worked on this codex are numerous and still today of debated attribution: the main miniaturist has been recognised in Matteo da Milano, from Lombardy and the court of Ludovico il Moro, who later worked on the ‘Offiziolo Alfonsino’. Other artists and copyists worked around him, such as Tommaso da Modena and Giovanni Battista Cavalletto; in the debate on the authorship of the decorations, the names of Andrea della Veze or Vieze and his son Cesare, Martino da Modena and Antonio Maria da Casanova have also been mentioned.

The connection with Savonarola

We have already mentioned the strong religious sentiment that drove Ercole, even in later life, to make pilgrimages and build religious buildings. Another testimony to this is the bond the Duke had with Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar of Ferrara origin who left the city in 1475. There was copious correspondence between the two in which the Duke’s search for a spiritual guide to satisfy his great religious fervour is evident. Through the Este ambassador in Florence, he kept constantly informed of the activities of the friar, whose sermons inflamed the Medici city, against whom Savonarola railed in opposition to all luxury and promoting penance as the only form of salvation. The friar’s accusations against the luxuriousness of the Church of Rome were also addressed to Pope Alexander VI Borgia and cost him excommunication in 1497. Ercole tried in vain to defend him against the accusations of heresy, but was unable to save him from being sentenced to death, receiving the news of his execution, which took place on 23 May 1498 in Piazza della Signoria in Florence, with great sorrow.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“The Court of Ferrara” in “Gli Estensi”, Ed. Il Bulino, 1997

Luciano Chiappini “Gli Estensi: a thousand years of history” – Ferrara: Corbo, 2001

Marco Folin “Un ampliamento urbano della prima età moderna” in “Sistole/Diastole Episodi di trasformazione urbana nell’Italia delle città”, 2006, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti – Venezia

Ada Francesca Marcianò “L’età di Biagio Rossetti Rinascimenti di casa d’Este”, 1991, Ed. Gabriele Corbo

“Commentario al facsimile del codice di Ercole I d’Este” edited by Ernesto Milano, Ed. Imago

Leoni Giovanni “La città salvata dai giardini. I benefici del verde nella Ferrara del XVI secolo’ in ‘Fiori e giardini estensi a Ferrara. La flora rinascimentale di Luca Palermo’, Leonardo-De Luca Edizioni, 1992

Giuseppe Lipani “Lo spazio antropologico del teatro. Biagio Rossetti e lo spettacolo estense” in Anthropologia e Teatro, Rivista di Studi, 2017

Silla Zamboni “Pittori di Ercole I d’Este”, 1975, Ed. Cassa di Risparmio Ferrara

Treccani Bibliographical Dictionary of Italians