Despite being an illegitimate son, born from the relationship between his father Niccolò III and Stella dei Tolomei dell’Assassino, Borso was the first Este to be elevated to the dignity of Duke, first of Modena and Reggio by Emperor Federico III, then of Ferrara by Pope Paul II.

His government lasted twenty years and was characterised by the long period of peace that he was able to maintain thanks to his diplomatic skills, bringing great prosperity to the territories he ruled. In addition to politics, he also dedicated himself to the improvement and expansion of possessions: he was especially involved in the grandiose work of reclaiming the marshy areas of Polesine and worked to extend the borders of Ferrara to the south-east in what is known as the ‘Addizione Borsiana’.

The fact that he was an illegitimate son characterised his entire The Life, characterised by the continuous manifestation of his virtues and aimed at legitimising his rule. In fact, Borso recognised himself in the Knightly ideal, both for personal affinities and to create an authoritative sovereign figure to regularise a government presided over by an illegitimate son. This ideal, in fact, was manifested through his image, which had to impersonate the virtues of good government: justice, religious devotion (see his personal interest in the Baptistery), chastity symbolised by the unicorn, generosity and all the other qualities that the Sovereign had to possess to be considered such. Unlike other important members of the family, for Borso even the arts were a way of achieving this goal: the ducal court, during his rule, was characterised by magnificence, an expression and symbol of power.

The Life

Borso was born on 24 August 1413 to Niccolò III d’Este and his mistress Stella dei Tolomei dell’Assassino, the third child after Ugo (who was beheaded by his father for his alleged affair with his stepmother Parisina Malatesta) and Leonello. An illegitimate son, but not for this reason neglected by Niccolò, who was sincerely attached to his mother Stella. For Borso, however, it was not so easy and that ‘mark’ accompanied him throughout The Life. Obviously also in the eyes of the other Italian courts, this condition of his put the house in a bad light, opening up discussions on the legitimacy of ruling and his own nobility. To remedy a situation that could undermine the stability of the state, Borso chose never to marry and not to legitimise any children, leaving the state in the hands of his half-brother Ercole, the legitimate son of Niccolò III.

From his childhood, his father encouraged him towards a military career, and it was also for this reason that he interrupted his literary studies early on (in fact, his difficulty in reading Latin is well known). He was sent into the service of Venice with a corps of a hundred lances, but his first years on the battlefield did not bring great satisfaction to young Borso.

In December 1441, on the death of Niccolò III, Leonello, Borso’s brother, came to power: the succession was legitimised by his father’s will, despite the fact that there were already two other legitimate heirs, Ercole and Sigismondo, born of Niccolò’s second marriage to Ricciarda da Saluzzo. Unfortunately for Borso, it was not a positive transition: the many years he spent outside the city of Ferrara did not allow him to have a part of the court in his favour, necessary to reverse this fate. The support offered to his brother during the succession was, however, rewarded with land and city possessions. He was also sent to the court of the Visconti in Milan: here he was received with honours and promises of future estates, but when Borso realised that this would not happen, he returned to Ferrara in August 1443 to reside there permanently.

However, his militancy in the Milanese armies was well rewarded: Filippo Maria Visconti gave him the city of Castelnuovo di Tortona (from 1570 Castelnuovo di Scrivia, province of Alessandria). This town had a special feature that made it of great economic value: it was one of the centres of production of guado (or gualdo), also known as ‘blue gold’. Its scientific name is Isatis tinctoria and it is a very valuable plant: by processing its leaves, a pigment is produced that can effectively dye fabrics a precious dark blue colour and, with appropriate mixing, purple can be obtained. Even the deep red colour, symbol of justice, that distinguished Borso, was obtained on a guado base. Thanks to this product, Borso was able to maintain power over the city for his entire life through a policy of advantageous tax agreements for the citizens and an increase in production, so much so that from 1452 he banned the use of cloth produced outside Ferrara.

After his return to Ferrara, he served his brother and the city, quickly becoming Leonello’s most trusted advisor and holding important positions. He soon obtained the credibility and influence within the court that he had previously been denied. Attracting many supporters to him, after Leonello’s sudden death, Borso was able to ascend to the government without direct opposition, except for that, expressed in his father Niccolò’s will. A prescription that the Council of the Municipality did not take into account, electing Borso unanimously. A few weeks later Pontiff Nicholas V also ratified the event, legitimising Borso’s government and the succession to his sons, or legitimate or legitimised brothers.

Policy

The historiography of the time of Borso and the historiography that immediately followed him portrays a very different figure from the one later recounted by 20th century historians. Borso’s leadership, in fact, brought the city of Ferrara great prestige, an extension of its borders and, as mentioned, a long period without wars that resulted in a situation of widespread prosperity. More recent historiographers, however, have emphasised how this tranquillity was essentially an expedient to make Borso perceived as a good and just prince, according to the code of knightly and good government of the time. While this assertion can be said to be true, also found in the most important public commissions, it is equally true that under Borso the territory he governed experienced a period of long economic prosperity and himself was the promoter of numerous important public works.

Moreover, the prestige that Borso gave to the House of Este is unquestionable: his first and perhaps greatest success was in fact that of obtaining from Emperor Federico III, in 1452, the title of Duke of Modena and Reggio, as well as that of Earl of Rovigo and Comacchio and the recognition of the territories conquered by Niccolò III in the Garfagnana.

The Emperor, on his way to Rome, was the guest of Borso together with his entire entourage (about 2,000 men) and here, for several days, he was entertained with tournaments and feasts. Federico III was received at the state border with the offer of fifty falcons trained for hunting and forty splendid corsairs, followed by eight days of ceremonies in his honour. The reception and gifts were so sumptuous that the Emperor decided to stop in Ferrara on his return journey as well. Thus, in early May, the Emperor stopped in the city again and, thanks to the sumptuous hospitality, rich ceremonies and the intervention of Enea Silvio Piccolomini, Borso was invested with the title of Duke. After days of feasting, also cheered by the marriage of Bartolomeo Pendaglia and Margherita Costabili, finally on 18 May 1452, Ascension Day, Federico III, after a solemn mass, elevated Borso to Duke of Modena and Reggio. The ceremony took place outdoors, on a richly decorated stage, at the Rigobello Tower and ended in the Cathedral, where the Duke took the loyalty oath. In the weeks that followed, Borso visited the cities of Modena and Reggio elevated to the new ducal title, which welcomed him with great honours and joy, the same enthusiasm that accompanied his transit also in the smaller towns.

Contrary to what he had hoped, his new dignity did not give him the opportunity to join the power games of the Italian states and his expansionist ambitions had to be shelved for the time being. Even the attempt to join the League stipulated between Milan, Venice and Florence in September 1455, in order to maintain his territorial integrity, did not bring Borso the hoped-for advantages.

In the meantime, the Italian chessboard of alliances was forming with Milan, Naples and Florence becoming ever closer and more allied to the detriment of an isolated Venice, which Borso decided to approach instead. In the meanwhile, Pius II had ascended the papal throne: Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini was a friend of Borso’s and this event gave him high hopes of obtaining political and territorial advantages. As he had done for the Emperor, Borso hosted the Pontiff in 1459 on his way through the Estensi territories on his way to Mantua to meet the Christian princes and press for a new crusade against the Turks. The Pontiff was received with the highest honours, but Borso was unable to convince him either of the concession of the Ducal title for Ferrara or of the abolition of the annual census paid to the Apostolic Chamber. The Pontiff’s refusal forced Borso to take a more detached attitude towards the Holy See’s policy. Also so as not to spoil relations with the Serenissima, who had no intention of taking part in the crusade, Borso distanced himself from operations towards Africa and the East, lands where he himself had excellent commercial relations.

These also concerned one of Borso’s greatest passions, that of horses. Attracted in fact by the French chivalric ethic and by that courtly world, he devoted himself to hunting with the best horses, to breeding dogs such as greyhounds and bloodhounds, to falcons and to organising tournaments.

Several times the Duke instructed members of his family and court to go and buy animals in England, Ireland, Germany, Sicily, and even to Africa. The first trip to the African continent took place in 1462, when Borso sent Rainaldo da Colle to Tunis: he returned the following year with ten Barbary birds, two lions, two ostriches, two dogs and other wonders from those distant lands that intrigued the Duke. On this occasion, the King of Tunis, Abu Omar Othman, sent Borso a beautiful horse as a gift and from here the exchange between the two rulers began.

Shortly afterwards, in 1464, another ambassadorship departed from Venice for Tunis with the intention, this time, of acquiring trailing horses. Borso, famous for his generosity and magnificence, sent the King rich gifts according to Italic custom and himself wrote a note that also contained precise instructions to his envoys (‘Instructione facta ai Nobili Scudieri de lo Illustrissimo Signore Duca di Modena etc, Gattamelata et Zoanne Iacomo da la Torre, per la loro andata in Barberia’). The letter contains Borso’s recommendations: do not cause a scandal, behave in an honourable manner, ‘lassare stare le femmine et ogni cossa lasciva’, take care that the glass does not break, and other advice on how to present gifts before the King, following a correct hierarchy. In the list of objects that Borso sent to the King we find: mules with decorated silk cloaks, knives, Murano glass, straw hats, chains and collars for dogs, cheeses, crossbows, guitars, falcon gloves, scissors from Modena, velvet chairs and other precious objects.

Returning to the Italian situation, and considering that the anti-Sforza and Aragonese policy was not bringing the hoped-for results, after 1468 Borso tried strategically to re-establish an alliance with the Holy See, proposing himself as an intermediary between Venice and the Pope: he actually succeeded in convincing the Serenissima to participate on the side of the Holy See in the war against Rimini, concerning the succession of Sigismondo Malatesta. This diplomatic success gave Borso greater credibility and strength, which led him to work, once again, to break the Sforza-Aragonese alliance. The rivalry with the Sforzas grew stronger and stronger, culminating in a criminal plan to kill Borso, when Duke Galeazzo Maria prevented the conquest of Imola and, in agreement with Piero de’ Medici, went so far as to plot the Pio di Carpi conspiracy.

The conspiracy against Borso came to life in the city of Carpi where the Pio brothers ruled the city together, but their sons had different ideas about which alliances to follow. Galeazzo Maria and Piero de’ Medici used these differences as leverage to plan the murder of Borso, supporting the rise to power of his brother Ercole. The latter, however, was not corrupted by the promises offered and told Borso everything, who had one of the Pious beheaded, arrested the conspirators and the other brothers, even those unaware of the plot.

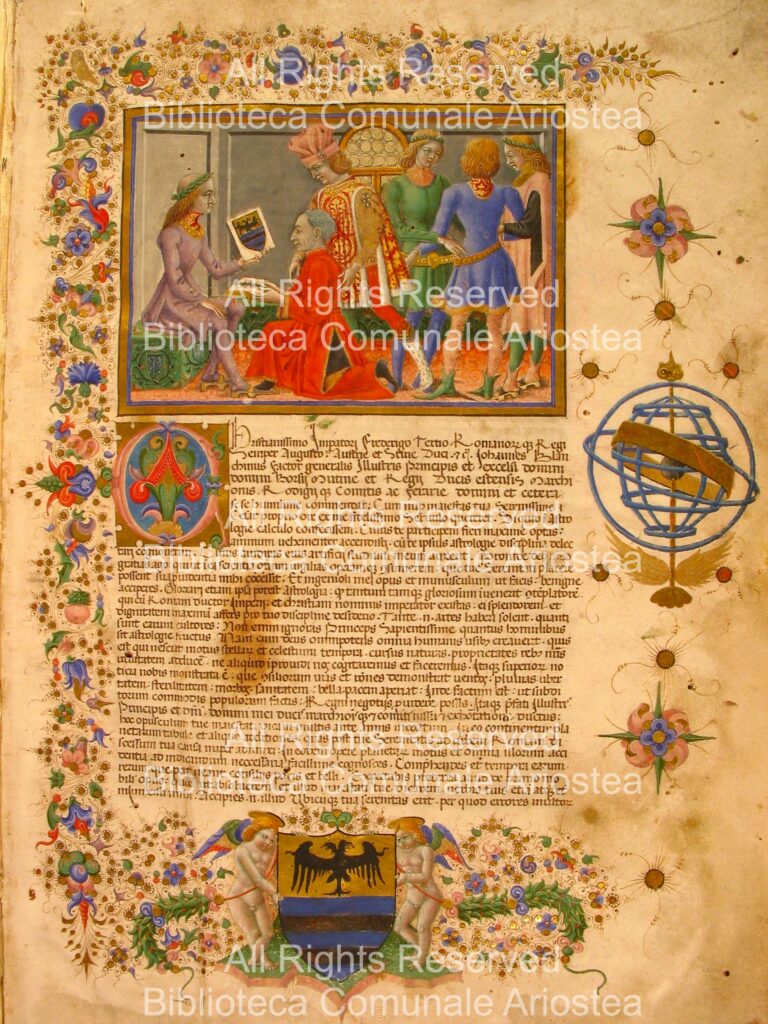

Meanwhile, thanks to the last strategic alliance with the Holy See, Borso’s other great goal – the title of Duke of Ferrara – finally arrived. The investiture came only in 1471, the year of his death, by Pope Paul II, born Pietro Barbo, who saw in this territory a valuable ally against the expansionist aims of Venice and, at the same time, an even more devoted supporter of the Church. The ceremony took place in Rome on 14 April 1471, Easter Day: Borso arrived in the eternal city with a procession worthy of a king and stayed there for almost a month, surrounded by grandiose celebrations. It should be emphasised that the Duke wanted to bring his famous Bible with him, to show off his magnificence and to display the power and wealth he had attained during his reign.

He died not long after returning to Ferrara, retiring first to Belfiore and then to Castelvecchio, where he died on 19 August 1471. As arranged from 1461, he was succeeded by his brother Ercole who, after the Conspiracy of the Pio family, had been presiding over the secret council with Borso for some time.

His funeral marked the last connection with the French courtly world and its symbolism, which was so present at Borso’s court. The funeral was a spectacular event: in addition to the magnificence associated with the sovereign’s dignity, the ‘great mourning Burgundian style’ was imposed on the funeral procession. This clothing included a cassock with a long drape and a large cap pulled down over the eyes, all strictly black. Finally, in accordance with the custom of knightly tradition, Borso’s heart and intestines were laid in a column in the church of San Paolo, while the body was buried in the Certosa. After the earthquake of 1570 and the subsequent reconstruction of the church, no trace remained of the column.

A period of splendour: Borso’s initiatives

Among the activities carried out for the benefit of the entire population by the first Duke, we must first of all mention the drainage of the marshes, especially in the Polesine area: from unhealthy and unusable areas, Borso gave back new fertile spaces to cultivate. The importance of this activity is even more evident in the reading of Borso’s personal actions reported in many works of art, among which those linked to the theme of draining the marshes stand out in number and importance: the unicorn plunging its purifying horn into the waters; the paraduro and the hedge, both symbols of the protection of the countryside from the floods of the river that become, in a more general vision, symbols of the Duke’s protective action towards his city and people.

Borso was also the promoter of a town-planning project, begun in 1451, that took the name ‘Seconda Addizione’ or ‘Addizione Borsiana’, perhaps less important than the later one implemented by Ercole I and for this reason probably passed into the background. Borso enlarged the boundaries of Ferrara to the south-east, turning a stretch of the Po into Via della Ghiara, including the island of Sant’Antonio in Polesine and tracing one of the first straight Renaissance roads. In addition, Borso is credited with the extension and ornamentation of numerous buildings from the Delizie Estensi of Belriguardo and Belfiore, Palazzo Schifanoia and Palazzo Paradiso, and the conclusion of the cathedral bell tower.

The University also experienced a period of vitality thanks to Borso, and in these years it was financed directly by the Camera Ducale.

Borso and art a debated combination

The image of Borso that has been transmitted to us is that of a man of a modest cultural level: he was not a fine scholar and probably only possessed the basics of the Latin language, preferring to read in French or the vulgar tongue, but he was not distant from the arts, literature and beauty. It is worth mentioning that Borso’s father chose a military career for him and therefore, unlike those who stayed at Court, his studies were interrupted.

Borso used art as a resource: in his great artistic projects, such as the fresco cycle of Schifanoia or the illustrated Bible, the work of art served to show and declare a value, a characteristic, a purpose and therefore the result was more important than the intellectual aspect. Borso did not spend his time arguing with intellectuals and painters about the subject matter to be depicted, which is probably why Borso was often considered to have little knowledge of art.

His public image was also devoted to these ends, which is why it was completely different from that of his predecessor Leonello: the hallmark of his figure as a prince was magnificence. Even his eccentricity in dress attracted the curiosity of his contemporaries: he wore brocade robes and gaudy jewellery, not only within the court or on special occasions, but always, even on country outings. The idea of magnificence pursued by Borso was the basis of his most famous commission, the ‘Borso Bible’, a splendid illuminated codex of great formal and stylistic refinement and enormous cost.

The two works that most emphasise the connection between Borso’s politics and art are the monument dedicated to him and the frescoes in the Schifanoia palace.

The monument was commissioned to Nicolò Baroncelli and completed in 1454. It was initially placed in front of the podestà’s residence, at the request of the people and as a sign of gratitude to Borso depicted seated while administering justice, holding the baton of command and the imperial cap on his head. On the sides, added at a later date, are four children each holding a shield with the Estensi’s insignia. The monument concludes with an inscription stating the reasons for this work: Borso became Duke of Modena and Reggio and under his rule were years of peace, for which he was described as a ‘giustissimo’ lord. When Borso died, the statue was moved to its current location – to the side of the entrance on Piazza del Municipio – although today we can only admire a copy of the original, which was destroyed in 1796.

Justice was in fact the virtue with which the first Duke continually tried to identify himself: in addition to the monument just mentioned, the depiction of Borso administering justice can also be found in the Salone dei Mesi in Schifanoia. Here, the subjects chosen for the frescoes show the virtues of the sovereign in a grandiose and triumphal language. After the enlargement of the palace in 1469, Borso dedicated himself to the decoration of the largest room, calling a large group of artists to work on it: Pellegrino Prisciani is recognised as the author of the iconographic programme, while the painters involved in this cycle were Francesco del Cossa, Cosmè Tura, Ercole de’ Roberti, Gherardo di Andrea Fiorini da Vicenza and a still unidentified ‘Master with wide eyes’, as well as an undefined number of assistants and helpers. The pictorial cycle is divided into twelve sections representing the months of the year. The reading of each month proceeds from top to bottom and is divided into three bands. The first is dedicated to the divine world through the depiction of the month’s patron divinity in triumph, the next presents the zodiacal sign of reference and the decans, while the last band depicts scenes from the earthly world of courtly life centred on the figure of Borso and the triumph of his virtues. The pilasters separating the scenes create the illusion of closed space overlooking scenes of everyday life under Borso’s rule.

Very interesting is a detail from the month of March, painted by Francesco del Cossa. In this portion Borso is depicted on horseback, in profile, surrounded by his retinue of horsemen and hunting dogs. The figure on Borso’s right has been recognised as Teofilo Calcagnini ‘the Duke’s companion’, a title that designated him as a true public office, obviously paid, that covered situations in the sovereign’s private life, from receptions to parties to ceremonies. The two had many common interests, and Borso’s predilection for Theophilus was made even more evident by the generous donations he bestowed on him over the course of time. The greatest of these took place on 25 December 1464, during the solemn Christmas mass, when Borso knighted him and invested him with the castle of Cavriago in the Reggio area, that of Maranello in the Modena area and that of Fusignano in Romagna.

Today we can admire seven of the twelve frescoed months, those from March to September.

Although Borso was not a lover and student of letters, he also possessed texts in French and under his rule we saw the affirmation of the vulgar language and the courtly culture that would be the basis of the future Duchy. Humanist studies certainly did not end in Ferrara, centred around the figure of Guarino Veronese, who continued in the line of his predecessors the care of the library. The texts that most interested Borso, of late medieval and early humanistic provenance, went to increase the library inside the tower of the Estense Castle, which was almost completely destroyed by fire. The sovereign thought about a new organisation of the library and, very importantly, conceived the library as an open space in which texts circulated freely among the professors of the state and in the court. Borso probably did not have a culture equal to the dignity of his titles, but he was very attentive to beauty, which is why the texts were carefully bound with precious materials. It is true that in these years there was a blossoming of illumination, the greatest work of which was the Bible already mentioned, but the religious books of the Charterhouse of Ferrara, also commissioned by Borso, are also worth mentioning.

If painting and humanistic studies were not explored in the same way by Borso, this was not the case for the minor arts. His predilection for splendour, in fact, brought new impetus not only to miniature art, but also to weaving, and there was greater refinement in tapestries, medals, carving, and the art of stage design to create stunning settings during ceremonies and public events.

Artists at court

Contrary to what usually happened at Court, Borso’s relationship with artists did not focus on cultural affinities or intellectual exchanges, but was simply finalized to the realisation of the works he commissioned.

In fact, in the first years of Borso’s duchy, various artists left Ferrara, in search of courts more interested in the work of painters, who were already penalised in those years by the fashion that favoured large tapestries decorated with scenes on the walls, and which, at the very least, limited their opportunities to paint. On the other hand, Leonello’s previous court was much frequented by artists and this weighed heavily on the economy of the Marquisate: Borso probably tried to reduce the number of painters at court also for this reason, focusing on the minor arts, which experienced a period of strong development with him.

Below are some of the most important artists at the court of Borso d’Este. Cosmè Tura (c. 1430-1495) was a versatile artist active at the court of Ferrara after 1456. At first he worked as a designer of cartoons for tapestries, then replaced Maccagnino as painter of the Studiolo by modifying the original design and succeeded Angelo da Siena as official painter of Borso’s court. When Borso died in 1471, Tura lost his central role at court, partly due to the return to the city in 1469 of Baldassare d’Este, who was given the role of official portrait painter. Tura was still engaged by Ercole I but in works of lesser importance, so much so that he later turned to religious commissions.

Baldassare d’Este (or Baldassare di Regio who died in 1441), Borso’s half-brother, was born in Reggio and served as a painter at the court of Milan until 1469, when he returned to Ferrara highly recommended by Galeazzo Maria Sforza. He immediately established himself as the official court portraitist. Unfortunately, only a few paintings by his own hand remain: of particular note is the ‘Portrait of Borso d’Este’ of 1469-71 now in Milan at the Castello Sforzesco. His greatest work (now lost) was a canvas completed after 1473, showing the duke, Alberto d’Este, Lorenzo Strozzi and Teofilo Calcagnini, all on horseback: the representation was intended to exalt the courtly friendship that united these characters. He continued his work at court under Duke Ercole I, until his death in 1504. For a time he was appointed governor of Castel Tedaldo, the important ‘blue gold’ (Isatis tinctoria, vulgarly ‘guado’) production town.

Francesco del Cossa (c. 1436-1478) was also a court artist: trained in the painting of Tura and the late Gothic style of Ferrara, he was part of the large group of artists involved in the ambitious project of the Salone dei Mesi in Palazzo Schifanoia. His hand has been recognised on the east wall, the one with the months of March, April and May.

Following a probable dispute over economic issues, he wrote a letter to Borso dated 1470 in which he solicited a large payment for painting a wall in Schifanoia and complained about the treatment he received from Pellegrino Prisciani, who treated him as a mere apprentice. The letter was forgotten by Borso and Cossa decided to move to nearby Bologna, to the court of the Bentivoglio family. This affair is often used to judge the Duke negatively as a patron of the arts and support the thesis that he was not an art connoisseur. As already mentioned, art was considered by Borso as a political instrument, especially in the case of Schifanoia. Moreover, it should not be forgotten that painters in the 15th century were considered to be mere craftsmen, while men of letters and astrologers such as Pellegrino Prisciani were held in high esteem and belonged to a higher rank.

Piero della Francesca (1406 or 1412-1492), already an affirmed painter, was called to paint in Ferrara around 1450, but no traces remain of his frescoes in Castelvecchio due to the enlargement of the palace ordered by Ercole I.

In literature, special mention must go to Matteo Maria Boiardo (1441-1494), who moved to Borso’s court in 1461 and ten years later accompanied him to Rome to receive the ducal title. He translated Greek and Latin works and composed poetic texts in Latin and vulgar. He also served under Ercole I, to whom he dedicated his greatest composition, the famous ‘Orlando innamorato’ (Orlando in love).

At that time, the poet Tito Vespasiano Strozzi (1424-1505), Boiardo’s uncle, was also at court. He held important positions in Ferrara, including governor of Rovigo and Polesine, as well as Giudice dei Savi (positions that continued under Ercole I). In addition, he wrote books in Latin and sonnets in the vulgar language: the epic poem ‘Borsiade’ dedicated precisely to Borso is worth mentioning.

As soon as he came to power after succeeding his brother Leonello, Borso was also the commissioner of a copy of Svetonius’ ‘Vitae XII Caesarum’: the manuscript presented itself as a perfect work to give prestige to the new prince through the memories of the ancient Caesars. The writing was commissioned to Giovanni da Magonza, while the miniatures to Marco dell’Avogaro: the work can be said to have been completed between 1452 and the following year.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“The Court of Ferrara” in “Gli Estensi”, Ed. Il Bulino, 1997

Luciano Chiappini “Gli Estensi: mille anni di storia” – Ferrara: Corbo, 2001

“Le Muse e il Principe Arte di corte nel Rinascimento padano” edited by A. Di Lorenzo, A. Mottola Molfino, M. Natale and A. Zanni (essays and exhibition catalogue) Ed. Franco Cosimo Panini, 1991

“Relazioni dei Duchi di Ferrara e di Modena coi Re di Tunisi” (Relations of the Dukes of Ferrara and Modena with the Kings of Tunis). Notes and documents collected in the State Archives of Modena by Cesare Foucard and published on the occasion of the third international geographic congress in Venice; Modena Tipografia legale – lithografia Pizzolotti – 1881

“Da Borso a Cesare d’Este La scuola di Ferrara 1450-1628”, Expanded Italian edition of the English language catalogue of the exhibition held in support of The Courtauld Institute of Art Trust Appeal, London, June-August 1984, Ed. Belriguardo, 1985

Corrado Padovani “Misteri e rivelazioni della pittura ferrarese. Repertorio di storiografia artistica estense” Ed. Liberty house, 2007 – Re-edition of C. Padovani’s book “La Critica d’Arte e la Pittura Ferrarese” of 1954

“Cosmè Tura e Francesco del Cossa L’arte a Ferrara nell’età di Borso d’Este” edited by M. Natale, exhibition catalogue, Ed. Ferrara Arte, 2007

Micaela Torboli “Il Duca Borso d’Este e la politica delle immagini nella Ferrara del Quattrocento”, Ed. Cartografica, 2007

Gianna Pazzi “Borso d’Este il “magnifico” di Ferrara”, Ed. Cosmopoli, 1935

Treccani, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Italians