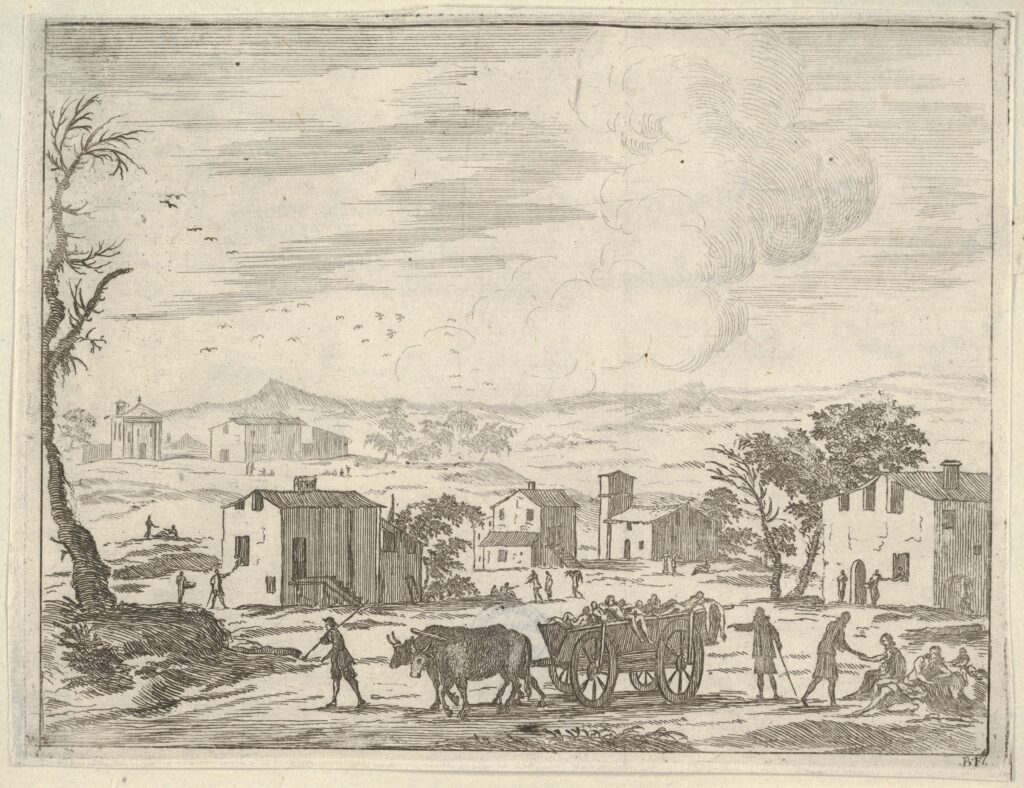

After the darkest page of Este history, which can be traced back to the Devolution of Ferrara to the Papal States (1598), with the loss of much of the territory that had belonged to the Duchy and of the city known throughout Europe for its architectural and artistic beauty, Duke Francesco I d’Este was the protagonist of the Este rebirth.

Francesco, in fact, was able to make the glory of the Este family shine again and his vision of magnificence was realised in an intense building activity that changed the face of Modena, the new capital. He was the patron of the two ducal palaces that still today are the image of the modenese duchy, the palace in Modena, symbol of political power, and the one in Sassuolo, a country residence whose baroque and illusionistic decoration fills all its visitors with wonder. In addition, the Duke was able to create one of the most important picture galleries in Italy and Europe, consisting of masterpieces by the greatest Italian masters such as Guercino, Guido Reni, Tintoretto and Veronese, and including his numerous portraits that found their highest artistic expression in the painting by Velasquez and the marble bust by Bernini.

In the management of public affairs, on the other hand, his bellicose spirit led him to conduct a risky policy of balance implemented through skilful and unscrupulous games of diplomacy between Spain and France, while still managing to retain possession of the Duchy.

His first years as Duke

Francesco I became Duke of Modena and Reggio on 24 July 1629 at the age of 19. The succession was not due to the death of his father but to his abdication as Alfonso III, after only 6 months of rule, chose the religious life by entering the Order of Friars Minor with the name of Giambattista da Modena.

Francesco was immediately called upon to deal with difficult political situations and despite his young age he showed decisiveness and diplomacy in handling them. The first adversity that presented itself to him was due to the dramatic Thirty Years’ War that was inflaming the whole of Europe: by paying a substantial sum, Francesco prevented the troops of lansquenets, under the command of Rambaldo di Collalto, from staying within Este territory, thus avoiding the probable acts of raids and violence that were notoriously carried out by these armies.

The year 1630 was characterised by two important events: the marriage with Maria Farnese, sister of the Duke of Parma Odoardo Farnese, and the epidemic spread of the plague, the same one recounted by Alessandro Manzoni in ‘Promessi Sposi’. After an initial moment of uncertainty, the Duke left Modena to avoid contagion, taking refuge in the countryside around Reggio, considered safer at the time. Francesco was in constant contact with the Council of State and his own secretaries to provide for the city’s needs despite his absence but, in the spring of 1631, the plague also infected Reggio, forcing the Duke to return to Modena. As a sign of gratitude for the end of the pestilence, Francesco financed the construction in Fiorano of the Church of the Blessed Virgin known as the Chiesa della Beata Vergine del Voto, where on 15 August 1634, the day of the Assumption, he placed the first stone of the building.

The first decade: a pro-Spanish policy

France and Spain were the two great powers that conditioned the destiny of European states and divided the Italian states in foreign policy choices, when the Peace of Westphalia was still a long way off (1648). The long-lasting survival of the Estense Duchy over the centuries was due to the Este family’s ability to reconcile divergent positions and to find effective mediations even in the thorniest negotiations. This was the situation facing Francesco I, who was also forced to move with skilful diplomatic manoeuvres between one alliance and another in order to maintain the State.

Francesco’s vision, however, was not limited to the survival of the Duchy but looked further: he wanted Modena to become a great capital admired by other sovereigns, without, however, abandoning the hope of repossessing Ferrara and Comacchio.

With regard to Spain, the Este family claimed a conspicuous credit that had never been paid, coming from the Capitulation of Milan and the marriage dowry of Isabella to Alfonso d’Este. To deal with this delicate matter, the Duke commissioned the Count Gian Battista Ronchi, whose ambassadorship also aimed to obtain the conferment of the royal title, already held by the Savoys and the princes of Tuscany. Despite his long diplomatic mission to Madrid, which lasted from 1629 to 1633, the year of his death, Spain was adamant and the Count failed to achieve what he had hoped.

The pro-Spanish policy followed in the first period of his rule brought Francesco disappointing results if one thinks, for example, that Count Ronchi only managed to obtain a vague and verbal declaration of ‘Spanish protection’ for the duke for about ten years. Despite this Francesco showed his loyalty to Spain by invading the Duchy of Parma, ruled by his brother-in-law Odoardo Farnese, guilty of siding with France. The only real benefit Francesco obtained from his loyalty to the Kingdom of Spain was the cession of Correggio. In 1634, in fact, Spain paid the penalty of 230,000 florins that prince Don Siro da Correggio was unable to pay (a penalty imposed on him by Ferdinand II on charges of counterfeiting coins), thus acquiring the rights to the city of Correggio, which, subject to reimbursement of the sum paid, he ceded to the Este family. The matter was only definitively concluded in 1649 when Don Siro’s son, in very poor financial condition, ceded the city to the Duke for good.

Francesco personally travelled to Madrid in 1638, bringing with him splendid gifts and believing he would be able to conclude advantageous agreements for the Duchy, but the courtesies reserved for him by King Philip IV of Habsburg brought only small assignments for some family members and many honours, such as the concession of the title of ‘Grand Admiral of the Atlantic’, the Toson d’Oro, and the appointment as Viceroy of Catalonia, recognitions that, deprived of the relative rewards, remained only lofty titles.

But the most important thing that remains of the Madrid ambassadorship is a masterpiece of art history, preserved in the Estensi Galleries in Modena: Francesco did not miss the opportunity to have himself portrayed by the court painter, Diego Velasquez. The portrait in question, an expression of refinement and elegance, may, however, not be the work commissioned by the Duke, but only the model painted from life by Velasquez, to later elaborate an equestrian portrait of Francesco I. This much larger portrait was never completed, probably also due to the changed political conditions between the two states that led the Duchy of Este to dissolve its alliance with Spain. The image of the Duke, in the work in the Estense Galleries, is characterised by the rapidity of the brushstroke and by that strong psychological value that Velasquez is able to convey in his portraits, coming into contact with the interiority of his subjects. Francesco is depicted in the guise of a condottiere: he wears a dark suit of armour, illuminated only by a few flashes of light, while on his chest he wears the necklace of the Toson d’Oro, partly covered by a red sash, a possible symbol of his recent appointment as ‘Grand Admiral of the Atlantic’. The young Duke is portrayed in a three-quarter view, his face revealing the distinctive features of his physiognomy such as his long nose, his slight upturned moustache and his thick, dark, curly hair that descends to his schooner, following the Spanish fashion. In the canvas, dominated by dark tones, only the light features of the face and the bright features of the red sash emerge vigorously from the painting. Velasquez’s dynamic brushstrokes leave a sense of ‘unfinished’ to the Duke’s profile, capturing his personality in an image that has become symbolic. After his stay at the court of Philip IV, Francesco became aware of the importance and role of art in the pursuit of political and propagandistic ends, and both art commissions and the number of artists at court multiplied from his return.

The First War of Castro

If Francesco dreamed of getting Ferrara and Comacchio back, Pope Urban VIII, born Maffeo Barberini, saw the Duchies of the Po Valley as an obstacle to the continuity of his own State. The expansionist aims of the Pontiff began with the desire to annex to the Papal State the small semi-independent dominion of Castro, belonging to the Farnese family. In September 1641 the situation precipitated and Francesco sided with the Farnese, along with Venice and Florence. The Duke’s hope was to gain international visibility and prestige and then claim back the territories ceded as a result of the Devolution, but at the conclusion of the war, he did not obtain concrete support for his cause from the allied states. The first peace treaty, with Castro remaining with the Farnese, was concluded thanks to the diplomatic work of France, which in this way skilfully insinuated itself into the Italian political scene. The second Castro war (1646-1649) would instead see the capitulation of the city into the hands of the Church.

Between France and Spain: a risky balancing policy

The diplomatic rapprochement of the Duchy of Este with France was to be long and laborious, characterised by numerous hesitations and ambiguous moves. It was France that first made an astute move in July 1645 when, through the powerful Cardinal Mazzarino, it granted the dignity of protector of the French Crown to Cardinal Rinaldo, the Duke’s brother. With this recognition, taken away from the Barberini family, began the uneasy bond that would unite the Este family to the Kingdom of France, whose relations were managed by Cardinal Rinaldo.

In August 1647 Francesco I thus began the risky and alternating change of alliances. While the Spanish were occupied with the revolt in Naples, the Duke took the opportunity to forge a Franco-Modenese agreement against Milan. However, the military operations were not a success, they suffered from the indecision of the commanders and the autumn weather conditions, while the Duke’s military incompetence compromised the conquest of Cremona.

Two years later, on 27 February 1649, Francesco renewed the alliance with Spain, pledging to no longer bind himself to France and renouncing the title of Protector of the Crown for Cardinal Rinaldo. But the volte-face made by the Duke in 1647 was not forgotten and despite the formal stipulation of the convention, relations with Spain changed, forcing relations between the two Sovereigns to mutual distrust and mistrust, cleverly concealed under the rules of diplomacy.

In 1655, the marriage between Alfonso, the Duke’s eldest son, and Laura Martinozzi, Cardinal Mazarino’s niece, marked the definitive rapprochement of the Duchy with France and thus the clear break in relations with the Kingdom of Spain. The balance was shattered and Spain promptly sent the governor of Milan, Don Luigi di Benavides Marquis of Caracena, to occupy Brescello and then move on to the Modena area and point at Reggio. The Spanish demands were the surrender of some Este fortified squares and the sending of the Duke’s sons as hostages to Madrid. Francesco did not accept such conditions and the city of Reggio was forced to courageously resist the assault, until the Spanish troops retreated into the Cremona area. The situation of uncertainty and the unheeded request for reinforcements led Francesco to astutely accept the appointment of Prince Tommaso of Savoia as commander of the Franco-Estensi troops. The latter led the army to the siege of Pavia, a choice that turned out to be wrong forcing the army to a hasty retreat, while the Duke was wounded in the shoulder. The dramatic military experience of Pavia added to other not very bright episodes in Francesco’s military career, convincing France to reduce military support for the Duchy.

In January of the following year, Francesco, accompanied by a large entourage of nobles, paid an official visit to Fontainebleau where he was received first by Cardinal Mazzarino and then by the King, with whom he then travelled to Paris. The magnificence of the French court and the honours reserved for him enthused the Duke, and the culmination was reached with his appointment as ‘Generalissimo of the French troops in Italy’, a role that remained vacant after the death of Tommaso di Savoia.

Back in Italy, he achieved a prestigious military success in the conquest of Valencia on 7 September 1656. He went on to besiege the nearby city of Alessandria together with his son Alfonso, who had rushed to fight at his side, but in August 1657, the impasse in which the battle found itself, added to the scarcity of provisions, forced the Duke to retreat.

The good reputation obtained thanks to the latest military successes induced Francesco to hypothesise yet another rapprochement with Spain: by purposely leaking rumours of this intention, he set up a subtle and risky game in an attempt to increase the financing and concessions obtained from France, which however did not bring the desired results.

He returned to Modena in December 1657, and in the early months of the following year he was again in battle to take the winter quarters in the Mantua area, inducing Duke Charles II of Gonzaga-Nevers to negotiate his neutrality. Having crossed the Ticino the following summer, he conquered, together with his son Almerico, the towns of Trino and Mortara, but his debilitated physique and the malaria contracted during the military operations left Francesco with no hope. Despite the doctors’ care, he died at Santhià, near Vercelli, on 14th October 1658. The body clothed in the Franciscan habit arrived in Modena on 4 November and was buried in the Church of the Capuchin Fathers. Today the body rests in the chapel of San Vincenzo inside the Church of Sant’Agostino, known as the Pantheon of the Estensi.

Marriages

The marriage to Maria Farnese lasted 16 years, during which time the couple had eight children, including the heir Alfonso IV (1634-1662) and Eleonora (1643-1722), a nun of the Order of the Discalced Carmelites, recognised today as venerable by the Catholic Church with the name Venerable Maria Francesca dello Spirito Santo. After the death of Duchess Maria, who died on 25 July 1646 in the Ducal Palace in Sassuolo, Francesco did not go far to choose a new consort, marrying his sister-in-law, Vittoria Farnese, in February 1648. The noblewoman died in childbirth in August 1649 and new negotiations immediately began for Francesco’s third marriage, this time it was necessary to weigh up the advantages offered by possible relations with France, Spain and the Papal States. The choice fell on Lucrezia Barberini, daughter of the prefect of Rome, great-granddaughter of Urban VIII and niece of Cardinal Antonio. The wedding was celebrated in Loreto in 1654, while the celebrations continued in Modena with a magnificent tournament in Piazza Grande. From this last marriage, Rinaldo d’Este (1655-1710) was born, who would be called upon by history to once again save the Duchy when, in the absence of heirs, he would have to undress the cardinal’s purple and continue the dynastic line.

The link established with the Barberini, one of the most powerful families in Rome, was viewed with hostility by both Spain and France. However, this did not hinder the Duke, who resumed difficult negotiations with Cardinal Mazarino to ask one of his nieces to marry his eldest son and future heir to the Duchy. Having reached an agreement, a marriage contract was drawn up between Alfonso and Laura Martinozzi, and the wedding was celebrated on 30 May 1655. The link with France was thus consolidated, forcing Spain to re-evaluate the Este alliance and its own position.

Modena, construction of a Capital

Francesco I d’Este was known for his authoritarian personality, politically unscrupulous actions and unlimited presumption that sometimes pushed him beyond his capacities. The desire to regain possession of the city of Ferrara remained only an ambitious and unrealisable dream but, as he could not get back the ‘first city of Europe’, he decided to elevate Modena to a true capital of the Duchy, worthy of hosting the Duke and his court. In the thirty years of his rule Francesco transformed Modena through renovations and new buildings, promoted culture and various art forms including theatre performances, commissioning and acquiring works of art to build his picture gallery.

From 1632 Francesco was involved in the transformation of the Ducal Palace in Modena from a defensive structure to a modern palace, symbol of the rebirth of the Este family. The Duke turned directly to Roman architects and it was a young architect, Bartolomeo Avanzini (1608-1658), who drew up the final design and supervised the work, which began in 1634. The project, which is characterised by a persistent adherence to 16th-century models, consists of a long three-floor façade, exalted at the centre by a structure with three arches characterised by a multiplication of decorative elements and a double roof-terrace, and ends at the extremities bordered by two small towers with rusticated corners. The presence of towers and roof-terraces, or in any case of elements that stand out in height with respect to the horizontal course of the façades, is a recurring motif in the great residential projects of the Roman Baroque: think of Borromini’s designs for the Pamphilj Palace in Piazza Navona or Rainaldi and Bernini’s designs for the Louvre. Their function, other than formal and stylistic, is eminently celebratory, with the purpose of exalting the presence of the princeps seen as the fulcrum of State life. Avanzini also obtains the greatest possible ornamental effect from the window finishes, arranged in the Ferrara tradition: here he imaginatively and vigorously mixes classical elements, not without drawing on Michelangelo’s inventive process for freedom of interpretation. After Avanzini’s death, work on the palazzo proceeded rather slowly and was also supervised by his pupil Antonio Loraghi.

At the same time as work began on the palace, Francesco commissioned the reorganisation and arrangement of the old garden extending behind the ducal residence. Avanzini designed a green space based on a series of avenues: the main one constitutes a continuation of today’s Corso Canalgrande, while another avenue cuts the first one diagonally joining the new ducal palace to a promontory used as a belvedere. At the end of the main prospect Francesco ordered Gaspare Vigarani to build the Palazzina dei Giardini, completed in 1634, probably intended for the refreshment of the Duke’s guests or also designed as a backdrop for the musical and theatrical performances that were staged in the garden.

The duke also thought about the security of the city by commissioning the construction of a fortified citadel, which was one of the prides of the house of Este in Modena. Work began in 1635, probably based on a design by the engineer Carlo di Castellamonte but with fundamental contributions from engineers and architects from Modena, such as Antonio and Francesco Vacchi and Gaspare Vigarani. The site chosen for the building, in the north-western corner of the city, allowed a direct connection with the Ducal Palace. It was a remarkable star-shaped construction, with five pike bastions and three crescents towards the countryside. After the Unification of Italy, the citadel was completely dismantled, today only the massive portal remains, which was the main entrance to the parade ground in the centre of the pentagon.

At the end of the plague epidemic of 1630, which claimed many victims in Modena, the Duke had two churches built as thanksgiving for the cessation of the contagion. The Chiesa del Voto was built in Modena and dedicated to the Madonna della Ghiara of Reggio, a city that was not affected by the contagion. The sacred building was designed by Cristoforo Malagoli known as Galaverna and represents the perspective backdrop of the ancient wood market (today’s Corso Duomo). The church was started in 1634, and inaugurated on 13 November 1636, the sixth anniversary of the end of the plague. Inside, the second altar is the actual votive chapel erected by the Community of Modena and contains Lodovico Lana’s beautiful altarpiece depicting the ‘Virgin with Saints Geminiano, Omobono, Rocco and Sebastian’.

The other church known as Santuario della Beata Vergine al Castello stands out with its towers and dome above the village of Fiorano. It traces its origins to a fresco depicting the Virgin and Child, a work believed to be miraculous for having escaped a fire set by Spanish soldiers and for having preserved the village from the plague of 1630. For these reasons, the Duke and the community deemed it necessary to erect a monumental sanctuary on the site, commissioning the young designer Bartolomeo Avanzini, who was already active in the Modenese palace, to undertake the task. Work proceeded slowly, so much so that one of the towers and part of the façade were only completed in the first half of the 20th century.

The building that best represents the rebirth of Este power after the Devolution of Ferrara, while at the same time celebrating Francesco I himself, is undoubtedly the Palazzo Ducale in Sassuolo: a residence of rare charm where the most scenic Baroque painting was experimented thanks to the work of artists such as Bartolomeo Avanzini, Jean Boulanger, Angelo Michele Colonna, Agostino Mitelli and Gian Giacomo Monti. Work began in 1638 and, after the death of Francesco I, was completed by Duchess Laura Martinozzi. The paintings that decorate the piano nobile are characterised by an accentuated illusionistic spirit, the same spirit that animates the entire palace: audacious perspectives and illusionistic paintings, where the reproduction of precious materials and the imitation of nature contribute to the dilation of space.

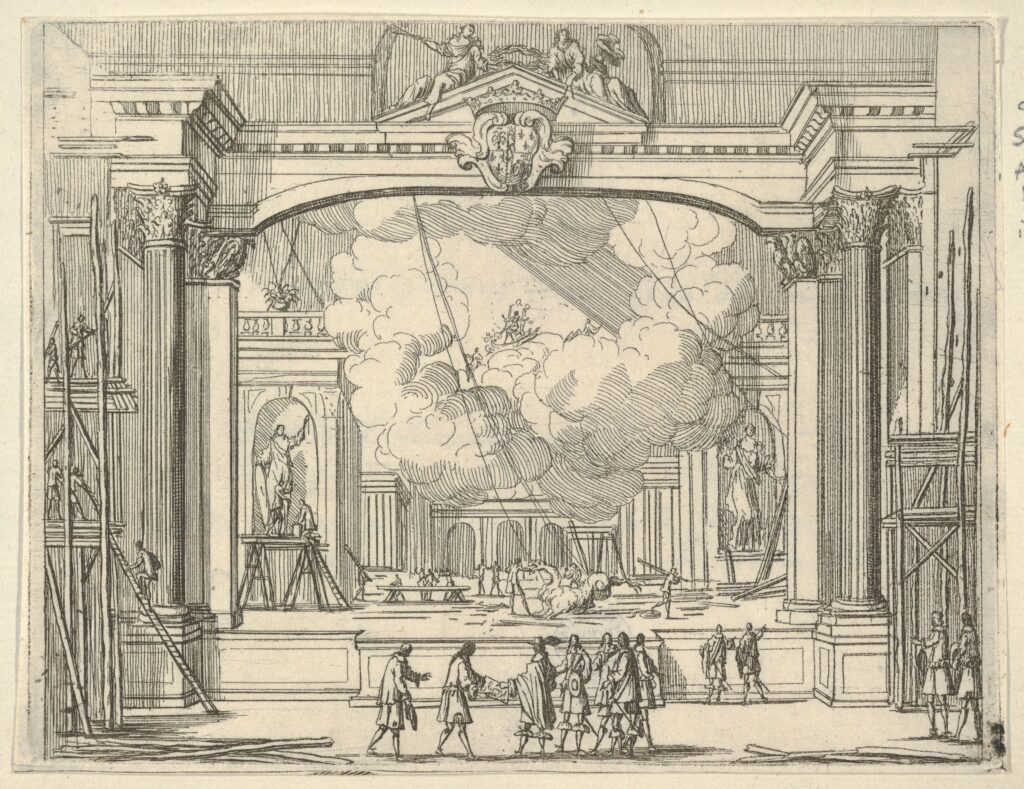

The square in front of the Ducal Palace of Modena was the place destined for the court’s shows where, with voluminous and creative ephemeral apparatuses, settings and scenographies were created. In 1654, Francesco began construction of the Ducal Theatre by placing it within the complex of municipal buildings overlooking Piazza Grande. The design was entrusted to the architect Gaspari Vigarani, who enlarged the volumes of the Sala della Ragione to obtain the necessary space for the theatre. The inauguration took place in the spring of 1656 and many performances followed until the Duke’s death.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61146231

The Art Collections of Francesco I

Francesco devoted himself to the creation of the new image of Modena as the capital of the Duchy, not only from an urban and architectural point of view through new buildings, but also by greatly increasing the art collections, to the point of making Modena one of the cities to visit on the Grand Tour of Italy. These works will be housed inside the Ducal Palace of Modena in the renowned Estense Ducal Galleria, arranged in a series of rooms in succession and preceded by the four Camere da Parata, which formed the introduction to the collection. The completion of the installation and the completion of some of the rooms took place in the four years following his death, by his son Alfonso IV.

First of all, the Duke had all the remaining works taken from the Ferrara properties, then he purchased paintings by artists from the Bolognese area such as Guercino, Guido Reni and Francesco Albani, then he chose paintings by Venetian masters such as Tintoretto, Veronese and Jacopo Palma the Younger, and finally Salvator Rosa and Hans Holbein.

Three huge canvases by Veronese ‘The Marriage at Cana’, ‘Going to Calvary’ and ‘Mary with the Infant Jesus, John the Baptist, Saint Jerome, an angel and the Cuccina family’ were purchased by the Cuccina family for the concession of a estate in Pontone, near Reggio Emilia, and the noble title of Count. Today, these paintings are kept in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden following the famous sale in 1746.

Nothing stopped the duke in front of a painting to his liking. His resolute and determined character led him to confiscate beautiful canvases from churches in the territory and replace them with copies painted by the court painter Boulanger. In this way entered into the ducal collection, paintings such as the ‘Deposition of Christ’ by Cima da Conegliano, ‘Mary with Child and Saints Anthony of Padua, Francesco of Assisi, Catherine and John the Baptist’, ‘Mary with Child and Saints Sebastian, Geminianus and Rocco’ and ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’ or ‘Night’ by Correggio, also masterpieces that were added to the collections of Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, following the sale of Dresden.

The painting ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’ by Correggio is recognised as one of the most beautiful nocturnes in Italian painting and already at the time of Francesco I was placed in a privileged position in the gallery, placed in the last room and presented to guests by solemnly opening the curtain covering it. Even in Dresden, where it is preserved today, it was for many decades the most renowned work, surpassed only by Raphael’s ‘Sistine Madonna’, when it became part of the collection of Augustus III of Poland in 1754.

The strength of this painting lies in the involvement it arouses in the viewer. A conventional and ordinary scene such as that of adoration finds in Correggio’s brush a new expression, a narrative power that is concentrated in Jesus who himself becomes light, called upon to illuminate the darkness. In fact, the illumination of the entire scene comes from the body of the Child, symbol of divine light, clasped in the arms of Mary who casts a gentle glance at him. The Mother is not bothered by the light emanating from her son; on the contrary, the woman next to her, on the left, is forced to shield her eyes. Vasari describes this scene as follows: “…and among the many considerations made in this painting, there is a woman who, wanting to physically look at Christ, and so that her mortal eyes cannot suffer the light of His divinity, which seems to penetrate that figure with its rays, puts her hand in front of her eyes, so well expressed that it is a marvel. There is a choir of angels above the stable singing’.

Beside the manger, in addition to the woman with the basket of birds, an old man and a young shepherd accompanied by a large dog have come to pay homage to the Redeemer, as have the five jubilant angels looking out from the dense cloud above them. Behind the Virgin, barely illuminated, is Saint Joseph with his donkey and two angels feeding the ox. In the background are gentle hills while the sun rises on the horizon. The representation takes place, as is traditional, inside an animal shelter, a place as humble and simple as the manger on which Christ is laid. The painter inserts a mighty column into the scene, a symbolic element of strength and solidity, on which the divine light shines, making the shaft emerge from the darkness of the night. In the foreground is painted a dense clump of wild grasses, whose leaves shimmer with golden highlights.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“The Este Duchy: Modena and Reggio Emilia” Bruno Adorni, pp. 354-369

“Francesco I d’Este, the most splendid of the Dukes of Modena” text of the conference by Graziella Martinelli Braglia held in March at Circoscrizione 1 Centro Storico – San Cataldo, Municipality of Modena, in the cycle of conferences “Illustrious Dukes and Modenese. A critical reinterpretation’, texts published in Modena, 2005

“Paris and Modena in the Grand Siècle. Gli artisti francesi alla corte di Francesco I e Alfonso IV d’Este” Simone Sirocchi, Trieste, EUT, 2018

“Le camere da parata di Francesco I d’Este nel Palazzo Ducale di Modena restituzione dell’allestimento originale” edited by Giovanna Paolozzi Strozzi with the collaboration of Patrizia Curti, Artecelata 2013

“Gli Estensi. A thousand years of history” Luciano Chiappini, Ferrara, Corbo Editori, 2001

“Gli Estensi. La corte di Modena” edited by Mauro Bini, Il Bulino edizioni d’arte