Tapestry production has been known since antiquity but during the Renaissance it experienced its golden age. The production of Flanders, and more generally of Franco-Flemish tapestries, was particularly renowned and it was from these territories that the Estense Court, always attentive to the fashions linked to the courtly world beyond the Alps, purchased directly or called Nordic tapestry makers to work in Ferrara.

Tapestries are characterised by workmanship between craft and art and were highly precious works, because they were woven with filaments of precious metals such as gold and silver and required lengthy elaboration. The design was executed by an established artist, usually a painter, who traced the full-size composition on a cardboard, which was then materially executed by a weaver. Due to their large size they were used to occupy large walls and also helped to insulate the cold walls of castles.

Unfortunately, very little evidence of Ferrara tapestries has come down to us; the certain traces point to this work and its copy, slightly later and with small variations, preserved in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

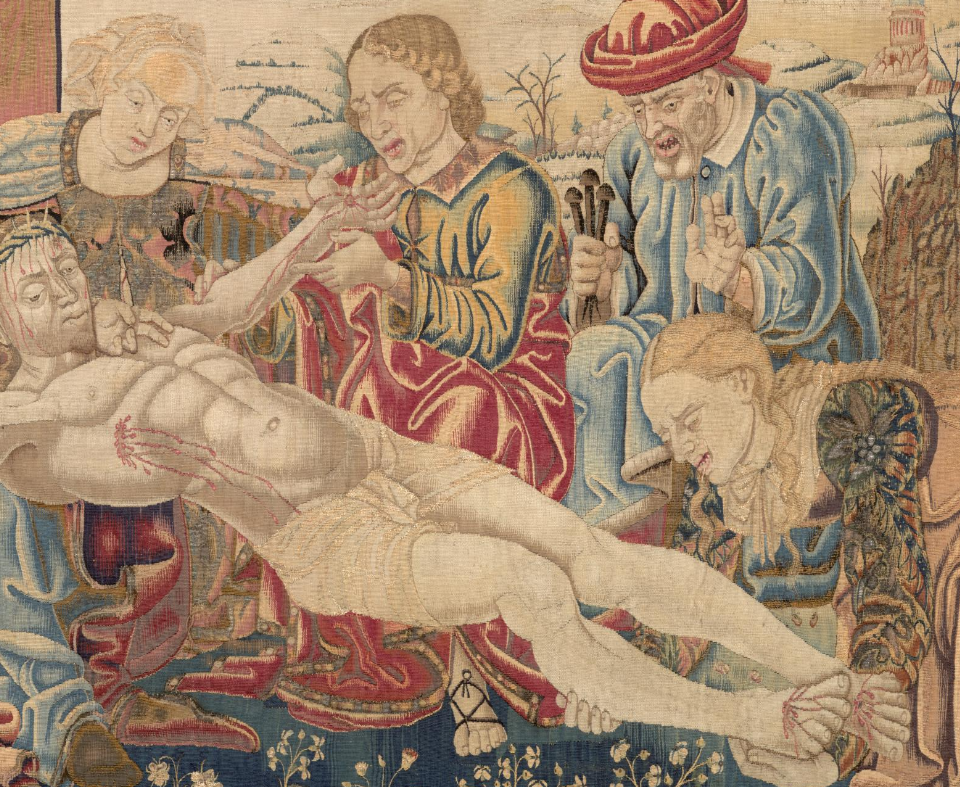

This tapestry covered the front of the altar (antependium) and depicts the ‘Pity of Christ’ with emphasis and richness of detail. The outer border simulates a trompe l’oeil with a metal border effect and set with precious stones.

Two other tapestries, dating from around the mid-16th century, are preserved in the Louvre and were probably commissioned by Alfonso I for the decoration of a Delizia.

The composition is rich not only in details, but also in a complex colour rendering that is particularly evident in the changes of tone, in fact the chiaroscuro is difficult to achieve by weaving. The foreground of the scene is occupied by the stiffened and strongly foreshortened body of the dead Christ. Around him at the base of the cross are six figures, identifiable from the left as two pious women supporting the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, Joseph of Arimathea holding the nails of the crucifixion in his hand and, at Christ’s feet, Mary Magdalene. The figures are described through the emotions that overwhelm them: their faces are contracted in pain and tears flow copiously. In the figures of St. John and the woman at his side, portraits of Ercole I and his wife Eleonora of Aragona have been recognised, an element that can identify the commissioner. Note the detail with which Eleonora is portrayed, in fact she wears a loose bodice on her abdomen, probably a symbol of pregnancy. The body of Christ emerges violently from the composition: the tense and defined musculature, the blood that, like a spider’s web, leaks from his hands and feet and his face deformed by pain charge the composition with pathos.

In the background on the right, two figures from behind are intent on removing the slab from the tomb, which will soon house the body of Christ. The landscape behind is composed of hillsides enriched with trees and architecture. At the feet of the figures sprout, from the rocky and arid earth, clusters of flowers including violets, daisies, carnations described with naturalistic precision.

The author of the cartoon has been identified as Cosmè Tura, while the executor was Rubino di Francia, already in service with Piero de’ Medici, who sent him to work at the Estense Court from 1458 to 1484.