Alfonso I d’Este was born in Ferrara on 21 July 1476, son of Ercole I d’Este and Eleonora of Aragona and brother of Ippolito, Giulio, Ferrante and Isabella.

He married twice to form alliances with other important families: first with Anna Maria Sforza and then with Lucrezia Borgia, with whom he had two children, the heir Ercole II and the future Cardinal Ippolito I. Proclaimed Duke of Ferrara on the death of his father in 1505, he faced and governed one of the most turbulent periods in the history of his lineage and the entire territory north of the Papal States, starting with the war against Venice. A war in which Alfonso’s victory at Polesella, achieved with a legendary feat of his land army against the very strong Venetian fleet, was to be decisive for the final solution in favour of the League of Cambrai led by Pope Julius II and of which Ferrara was also a member. However, this alliance was not enough to prevent a sort of personal war between Julius II and Alfonso I, which resulted in excommunication and the loss of various territories. A quarrel that ended only after the death of the Pope and the arrival of his successor, Leo X. But the relationship between Alfonso I and the Holy See remained complicated, so much so that the pontiff himself, like his predecessor and also his successor, excommunicated Alfonso. Despite this, thanks to his military abilities, combined with the talent with which he built new pieces of artillery himself and the political strategies he managed to deploy, Alfonso I still managed to keep the House of Este in power (he was succeeded by his son Ercole), but above all he contributed to increasing its prestige through artistic works, from Titian to Battista and Dosso Dossi, through literary works such as Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, to architectural works, traces of which remain to this day in his splendid ‘Delizie’, castles and fortifications.

The life: family and marriages of interest

Alfonso I was born in Ferrara on 21 July 1476, the third son of Ercole I d’Este and Eleonora of Aragona His name, new in the Este genealogy, was chosen to commemorate his maternal great-grandfather Alfonso V of Aragona Also unusual is his non inclination towards the study of literature and music, as the standards of court expected, preferring physical exercise and the mechanical arts, excelling in manual activities (hence the nickname ‘prince craftsman’) such as woodworking, ceramics and metalwork. The latter was the sector that gave him the greatest satisfaction: with intuition and extraordinary talent, Alfonso created and modified war instruments, which would be fundamental during the numerous battles in which he would play a central role.

From these inclinations, quite different from those of his predecessors, Alfonso positioned himself as a new type of aristocrat with a humble and unpretentious lifestyle. But not for this reason distant from the duties of court. His father Ercole, in fact, with the intention of consolidating the good relations between the dynasties and above all stopping the Venetian expansion, had signed a marriage contract with the Duke of Milan with his daughter Anna Maria Sforza, just as soon as Alfonso turned one, on 21 July 1477. Three years later, the alliance with the Sforza family was again strengthened with the marriage vows between Alfonso’s sister, Beatrice, and Ludovico il Moro.

A childhood, therefore, marked by the constant political and social developments of the Este family. 1482, in this regard, was a particularly turbulent year: Alfonso and his brothers were forced to leave Ferrara, threatened by both war with Venice and the plague, and move to the city of Modena where they remained for two years.

Back in Ferrara and having reached the age of majority, the future Duke married, the wedding being celebrated in Milan on 23 January 1491. Alfonso I and Anna Maria Sforza later renewed their marriage vows also in Ferrara in the Ducal Chapel, in the presence of numerous ambassadors from all over Italy. Unfortunately, this union lasted only a few years and left no heirs: Anna died on 2 December 1497, during childbirth, probably from complications of syphilis contracted by her husband, and the child she was carrying also did not survive.

As was the practice at the time, negotiations for a new marriage began shortly afterwards and as with the previous one, it was her father Ercole who conducted the negotiations and persuaded Alfonso to accept the marriage to Lucrezia Borgia. She was the daughter of Pope Alexander VI, born Rodrigo Borgia, a guarantee of good relations with the Church, and therefore a guarantee of a magnificent dowry of more than 100,000 gold ducats for the State treasury, including the lands of Cento and Pieve di Cento, as well as the granting ab perpetuo of the succession of the Duchy of Ferrara to all male descendants.

The wedding took place on 29 or 30 December 1501 and Alfonso’s brother, Don Ferrante, was sent to represent the groom. After a few days Lucrezia left for her new city, where she arrived only a month later after a long and tiring journey. On her arrival, the city of Ferrara was in a festive mood, ready to welcome the new princess: the celebrations and banquets in her honour were grandiose and lasted eight days. The union between Alfonso and Lucrezia was very solid, with the lady of the House of Borgia proving to be up to court duties. Lucrezia gave birth to the long-awaited male heir for the future of the Duchy: Ercole was born on 4 April 1508, in great celebration in both Ferrara and Modena. On 25 August 1509, Ippolito was also born, destined like his uncle of the same name to become Cardinal.

Unfortunately, the death of Alexander VI in 1503 interrupted the political tranquillity and put an end to the many benefits that the union with Lucrezia could have brought to Ferrara and the Este power. In the same year, Ludovico Ariosto entered the service of Ippolito d’Este, Alfonso’s brother.

The early years as Duke: discontinuity from his father

Between the end of 1504 and 1505 Duke Ercole’s health became so bad that Alfonso, in respect for his father, prohibited carnival celebrations. The death of Ercole, second Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio, came on 25 January 1505 and, after just four hours, Alfonso was promptly proclaimed Duke. His shy and reserved figure, devoted to manual activities that were considered minor and unsuited to the figure of a Prince first and a Duke later, had made him unpopular and rumours indicated that he was completely incapable of governing. But Alfonso, in order to demonstrate his qualities, was able to tenaciously govern his state in one of the periods of maximum political instability that affected the entire peninsula.

As the first acts of his government, the new Duke worked to eliminate the heavy duties imposed by his father to pay for military and building expenses. Not only that, he bought grain from Venice and distributed it to the needy to combat the enormous famine that was starving the state, and also faced an epidemic that caused thousands of deaths.

The foiled conspiracy of Giulio and Ferrante

More than from external enemies, the new Duke had to guard against the rancour of his own family, in particular his brothers Giulio and Ferrante, of whom he had great esteem. An episode that occurred near the Delizia di Belriguardo tells of these complicated relations. Here Don Giulio had crossed the way to Cardinal Ippolito, who was with his men. The latter, apparently at their master’s urging, attacked him, hitting him in the eyes and leaving him for dead. Duke Alfonso, learning of the incident, was furious at the violence committed by his brother, so that the Cardinal was forced to retire for a while, first to Mirandola and then to Mantua to his sister Isabella. Giulio, meanwhile, was treated by the best doctors in Ferrara and stayed at the castle in a dark room so as not to offend his eyes, which never fully healed. Alfonso, however, did not have the courage to be too harsh with Ippolito (who later became his right-hand man and faithful advisor) and asked for their reconciliation.

Perhaps to take revenge on Ippolito and Alfonso’s too much benevolence, when his health improved, Giulio, in agreement with Ferrante, planned to kill the two brothers. They were joined by some feudal lords and servants hostile to Alfonso. But for some time Ippolito had the two brothers under surveillance and soon discovered the plot of the conspiracy they were planning: when the Duke returned to Ferrara after a journey that lasted several months, the delicate situation was exposed to him and the interrogations immediately began. The legal proceedings proved the responsibility of all the conspirators and Alfonso, who had been struck down in his dearest affections, made no secret of his sadness. All were sentenced to prison, even Ferrante and Giulio, who were, however, treated with consideration, especially after their first years in prison. Ferrante died in prison in 1540, while Giulio was pardoned in 1559 by his nephew Alfonso II.

The League of Cambrai and the victory at Polesella

The Duke’s first major political-military operation was the alliance, led by the Holy Church, against Venice. Alfonso in fact joined the League of Cambrai, which also included Maximilian I of Habsburg (Holy Roman Emperor), Louis XII (King of France, Duke of Orleans), Ferdinand II of Aragona (King of Naples and King of Sicily), Carlo II (Duke of Savoia), Francesco II Gonzaga (Marquis of Mantua) and Ladislaus II (King of Hungary) led by Pope Julius II, born Giuliano della Rovere. Alfonso was appointed Gonfaloniere of the Holy Church in 1509 and with this honour prepared himself for the war that began on 27 April with the excommunication of Venice. After numerous victories of the League, Alfonso managed to regain the territories of Polesine and Rovigo, lost in 1482. In July Padua returned to Venetian possession and later, to complicate matters, Venetian troops captured Francesco Gonzaga, husband of Isabella d’Este, and imprisoned him. Thus affected on both the military and personal fronts, Alfonso became even more deeply involved in this war, winning some of the most important and decisive victories in history, including that of Polesella. A battle conducted without the support of either the Pope or the other allies of the League of Cambrai. This victory is still celebrated in military strategy books today because the Estense army succeeded in the feat of subduing the Venetian fleet. After a long and painful battle, Alfonso found an unexpected ally in the bad weather: in December the heavy rains had swollen the Po River and the Venetian boats, which were waiting for battle, had risen following the rising waters almost to the banks, so that they were exposed and vulnerable. The Este troops immediately gained a strategic position, hurriedly and secretly bringing in artillery from Ferrara: on the night of 21-22 December 1509, Ippolito alone commanded the troops and ordered the attack on the Venetian fleet, almost completely destroying it. Compliments and esteem for the Cardinal were unanimous, but also congratulations for the Duke’s excellent military engineering. To crown this memorable success, the two victorious brothers entered a festive Ferrara, sailing on the most beautiful of the boats taken from Venice, the last of a long procession that paraded from the port to the cathedral, where a mass of gratitude was celebrated.

Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7832558

The relationship with the Church: the ‘personal war’ with Julius II

Alfonso I always had a difficult relationship with the Holy Church, more for personal reasons than for expansionist ambitions of his own kingdom. Although he had participated in the war against Venice in the League of Cambrai and had shown himself to be an excellent military leader and strategist, Julius II was unable to consider him as one of his true allies, mainly because of the Duke’s loyalty to the King of France. This was the first reason that decreed the break between the Pontiff and the Duke: the Pope, in fact, after having absolved Venice from excommunication (1510) had expanded his political vision, setting as his first objective that of limiting French control in Italy, starting with his allies, including the Duke of Ferrara; the latter, for his part, did not cease fighting against Venice at all to conquer new territories, despite the new papal position. At this point the Pope had to intervene directly, imposing the cessation of hostilities against Venice and also the immediate termination of the alliance with Louis XII, on pain of excommunication. Alfonso did not back down from his position and on 9 August 1510 he was excommunicated, with the decadence of his throne and his ecclesiastical estates, including Ferrara, and the deprivation of the Gonfalonierate of the Church (promptly conferred on Francesco Gonzaga). Immediately after this, Modena surrendered to the papal forces without even a fight (its reconquest would later characterise Alfonso’s entire life), just as the Polesine returned under Venetian control. The war continued with alternating fortunes – to be remembered is the victory at Bastia where the Duke showed great courage and military valour – and after almost two years of bloody battles and near agreements, Alfonso reached Rome to ask the Pope for absolution from the many faults he had committed against the Church, so as to be absolved of excommunication. However, Alfonso’s request also had to go through the cardinal’s commission, which would have taken a long time. Alfonso, forced to stay in Rome, found himself spending his days wandering through palaces and ecclesiastical collections of art objects. It was on this occasion that on 11 July 1512 he met Michelangelo while he was painting the Sistine Chapel and was fascinated by his art, insisting on having one of his works.

In the meantime, the request made to the Pope went ahead, but at Alfonso’s supplication Julius II made demands that were intolerable for the Duchy. Immediately it became clear that the Pope had no intention of coming to an agreement with Alfonso, whose stay in Rome endangered his own life. With the invaluable help of the Colonna family, Alfonso escaped from the city: changed in clothes and unrecognisable, he managed to leave Rome and, still in disguise, began his arduous journey to Ferrara. The conflict with Julius II had now crossed the political line and become personal. In the meantime, the situation for Ferrara was extremely difficult: by now openly in the sights of a furious Julius II, the State in the absence of the Duke was ruled by Ippolito who, despite losing other territories, continued strenuously to defend it, continuing the fortification of the walls and going so far as to sell the Estensi’s jewels to pay for military expenses. To prevent enemy troops from marching overland towards Ferrara, Ippolito had to give the order to break the banks of the Po to flood the countryside. Despite this, the population, exhausted by now, continued to remain loyal to the Este family and placed all their hopes in the beloved Cardinal and the hoped-for return of Duke Alfonso. Which happened on 14 October 1512: the Duke, after more than three months living as a fugitive, entered the garden of the Estense Castle, causing the joy of the people of Ferrara. The city bells rang out in celebration and the people came to see him and acclaim him. Alfonso immediately set to work for the city and its possessions. They had to be defended and probably prepared for more battles. The turning point came a few months later, when on the night of 20-21 February 1513 his enemy, Julius II, died. History records that not even on his deathbed did the Pope lay down hostilities against Alfonso, referring the dispute to his successor.

A new Pope, a new excommunication: Leo X

As successor to Julius II, Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, son of Lorenzo il Magnifico, was elected under the name of Leo X. The notice was greeted with celebration in Ferrara, as it was hoped that he would be a pope friendly to the Este family, given the strong relationship that united him to the Gonzaga. Indeed, the new Pope immediately suspended the interdict and excommunication on the Duke, his family and all his citizens. Alfonso decided to go and meet Leo X in person, also to resolve the important issues concerning his possessions: the restitution of the salt pans of Comacchio (with the clause that the Duke could extract from them the salt necessary for the sustenance of Ferrara) and the return of the city of Reggio, which for the Church had never belonged to the House of Este. Negotiations began with friendly talks and lunches, which gave Alfonso hope. A vain hope, since even this Pope certainly did not turn out to be a friend, nor a very loyal interlocutor with the Duke. In fact, a pact was concluded. This provided for: the exclusion of the Comacchio salt pans from the Estensi’s possessions, only the promise to conclude the Reggio issue as soon as possible and the return of the title of Gonfaloniere of the Church. Alfonso therefore returned to Ferrara with almost empty hands: in one there was the loss of the Comacchio salt pans and in the other only promises.

Not even the neutral policy with the French and Venetians yielded good results: Emperor Charles V ceded the city of Modena to the Pope in return for 40,000 ducats and Leo X promised to return it to the Duke of Ferrara in return for the same amount of money. The Pope, among other things, made a secret alliance with Ferdinand the Catholic, while in France Francesco I succeeded Louis XII, recovering the Duchy of Milan. The Pope, frightened by further French expansion in Italy, immediately negotiated an agreement. Alfonso had fought as an ally on Francesco I’s side and therefore hoped that his territories would also be included in the demands made, as was then the case: the King imposed Leo X the restitution of Modena and Reggio to the Duke, against payment of a substantial sum. For Alfonso it was a victory more political than military, but this was not to be the end of the tormented relationship between the Pope and the Duke.

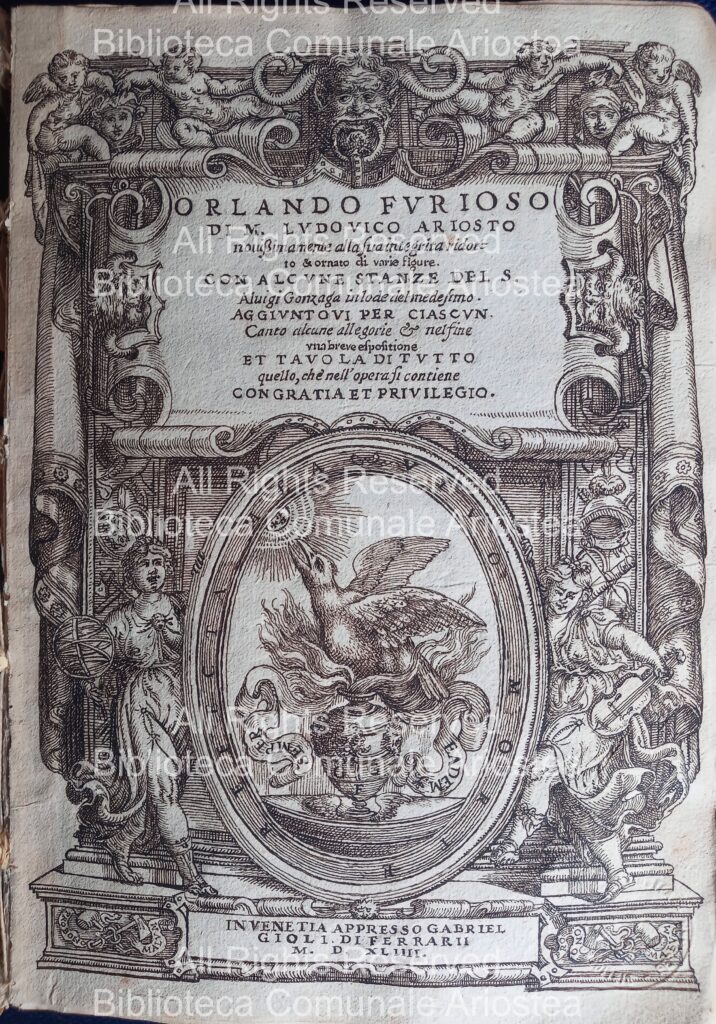

It was in these difficult days for the fortunes of the Duchy that Alfonso found refuge in the arts and, in particular, in the vision of Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Feast of the Gods’, or in the other works he was surrounding himself with: in fact, from the second decade of the 16th century, a vast artistic activity was launched that would continue until the end of his reign. Dosso Dossi became the official court painter and in the sphere of architecture Biagio Rossetti was commissioned to design the Delizia del Belvedere, which was built from the summer of 1513 while works continued on the city walls and defensive bastions. These included the construction of the ‘Montagna’ (mountain), a defensive system dominated by an artificial hill at the ancient Borgo di Sotto. Of a different kind were the interventions on Via Coperta that in the construction of the famous ‘Camerini d’Alabastro’ created a space for the Duke’s art collections. In 1516, Ariosto published ‘Orlando Furioso’ dedicated to Cardinal Ippolito (second edition February 1521 – third edition October 1532). In the same year Fra Bartolomeo was commissioned to paint ‘The Feast of Venus’, his first non-religious subject, of which only the preparatory drawing remains, a work destined for one of the Camerini. The drawing was given to Tiziano, which the artist distorted in the composition. The finished canvas, now in the Prado Museum, arrived in Ferrara in 1519 and Tiziano decided to personally preside over its installation.

Relations with the Papal States remained difficult for the Este family; indeed, not even his brother the Cardinal managed to build a good relationship with Leo X. Due to these conflicts, Ippolito considered it wiser to confirm his appointment as Bishop of Buda, Hungary, where he would reside for a long period together with all his servants. Ludovico Ariosto, however, was firmly opposed to moving there and for this reason was dismissed by Ippolito, but in 1517 Ariosto resumed service as a stipendiary under his other brother, Duke Alfonso I.

Without his trusted brother at court, Alfonso also had to face the unexpected tragedy of his sister Isabella, widowed after the death of Francesco Sforza on 29 March 1519. Thanks to Alfonso’s advice and closeness, Isabella still managed to govern Mantua until her son Federico came of age.

A few months after the death of his brother-in-law, on 24 June, Alfonso also lost his wife: Lucrezia was expecting a daughter, but unfortunately the pregnancy ended in the death of both.

After the solemn funeral in a city in deep mourning, Alfonso spent the summer of 1519 in Belriguardo, between civil duties and building activities. At that delicate time, between the death of Lucrezia and his brother Ippolito in Hungary, Alfonso fell seriously ill, becoming easy prey to the ever-active expansionist intentions of the Papal States and Leo X in particular.

But political dynamics changed rapidly in those years, as did alliances. This is demonstrated by the secret agreement between the Pope and the King of France, who were officially enemies: Leo X promised to defend France and deny Carlo V the Kingdom of Naples, while Francesco I promised to defend the Papacy against Carlo V and any insubordinate feudal lord. It was in this situation that Leo X, the Bishop of Ventimiglia Alessandro Fregoso and Cardinal Giulio de Medici conjured up a secret plan to conquer the city of Ferrara. Alfonso soon learned of this, informed directly by his sister Isabella, and despite his illness, he prepared for battle with determination and courage. He quickly fortified the city, then looked for allies: among them, he obtained the invaluable support of Federico Gonzaga, who did not allow the enemy troops to pass along the Po. This move cost time and, above all, revealed the plan, so much so that the bishop decided to renounce the attack and Leo X declared his total extraneousness to the affair. The notice of the plot attempted by Alessandro Fregoso prompted Ippolito’s return from Hungary, who made his solemn entrance into Ferrara on Easter Sunday 1520. The Cardinal’s summer passed peacefully in the ‘Delizie’ in search of rest and refreshment, but towards the end of the season Ippolito’s health suddenly worsened. Death came between the night of 2 and 3 September, at the age of 41. Ippolito had already appointed Alfonso as universal heir to his patrimony, who took charge of the support of his brother’s family, including their two children, apparently with the singer Dalida de’ Putti, who were born and raised in absolute secrecy. Although Leo X recognised the validity of the will, it was a difficult process to have his brother’s very rich inheritance recognised.

In the meantime, Leo X changed strategy again and allied himself this time with King Carlo V, officially to eradicate all forms of heresy, but also to drive out the French. And of course the city of Ferrara was always in the plans of the Pope, who wanted to re-annex it. With these conditions, the Duke also began to enlist soldiers to fight a imminent war, which he would face with a newfound courage, thanks to the relationship he had just begun with the young Laura Dianti.

In this period Tiziano was again in Ferrara to paint, around 1522, the portraits of Dianti and Alfonso, the first of which is now in a private collection in Switzerland and the second lost. The Venetian artist also completed the painting ‘Gli Andrii’ for the Duke’s private flat in the Camerini Dorati.

As expected, Alfonso took the field for battle and in just three days reconquered the towns of San Felice di Finale and Parma, which was soon after recaptured by the French, while almost the entire Garfagnana, recovered by Alfonso in 1513, came under Florentine control. This was not the only victory for the papal army, which conquered many territories and in October headed straight for Ferrara. Leo X, who had absolved Alfonso I from excommunication at the beginning of his pontificate, excommunicated him and the city of Ferrara again. The battle began between Bondeno and Ospitaletto, but Alfonso was soon forced to retreat within the city walls, where he called back all his officers to defend the city, which after the fall of Milan remained the Pope’s main objective.

The unexpected death of Leo X in December 1521 favoured Alfonso, who managed to recover part of the lost territories. As a result, Garfagnana and Frignano spontaneously returned under the Duchy and Alfonso sent a new and illustrious governor, Ludovico Ariosto, to those territories, who was forced to accept the important task entrusted to him.

At the side of Carlo V against the League of Cognac

The brief pontificate of Adrian VI, born Adrian Florisz, formerly bishop of Tortosa, did not change the direction of relations between Alfonso and the Papal States in any way, but it did bring the suspension of the interdict on Ferrara and a few years of relative tranquillity in the Duchy. The absolution of the excommunication, on the other hand, cost the Duchy a lot: to please the new Pope, in fact, Alfonso signed an agreement with the legate city of Bologna, which turned out to be disastrous for the river economy of the territory. In practice, the Bolognese would put the Reno back into its original riverbed near Cento, causing Ferrara to lose the security of having the southern part of the city protected by the river, without considering the commercial damage due to the loss of duties on the traffic of merchandise and people. However, the operation was successful: Ercole II represented the House of Este before the new Pope and on his return brought with him the document absolving him from excommunication.

Refreshed by this notice and, above all, after recovering from a long illness, Alfonso took advantage of the truce to also take care of his brothers Julius and Ferrante, still imprisoned after the failed conspiracy, by assigning them inside the castle, a room with windows above the tower of the Lions.

But the period of tranquillity soon came to an end with the death, also sudden, of Adrian VI. Alfonso immediately took advantage of the opportunity to retake both Modena and Reggio, which had been lost since 1510: the latter city, without bloodshed, decided to return under the Duchy, followed by Montecchio, Castelnovo di Sotto and Brescello. The attack on Modena was instead postponed, because Alfonso was waiting for reinforcements, but in the meantime a warning from the Church arrived and was hung on the door of Modena Cathedral. Alfonso’s hope was confined to the election of a friendly Pope, willing to confirm his newly conquered possessions. But hope vanished when Giulio de’ Medici was elected as Clement VII, who immediately exhorted the Duke to lay down his arms and stop his advance. Alfonso was forced by circumstances to stop in order to continue the negotiations that were to be opened for the possession of Modena and Reggio. The diplomatic mission to the new Pope ended only with the agreement of non-belligerence for one year.

In the meantime, however, Alfonso continued the fortification works, completing the Bastion of San Rocco in 1524, equipped with cannons and other weapons, which became the spearhead of the defence system. In September 1525, the Duke left for Madrid, to negotiate directly with Emperor Carlo V over the issue of Modena and Reggio, also reassured by a temporary suspension of the trial against him for occupation of ecclesiastical land, granted by the Pope. However, the truce was not respected, in fact in Grenoble Alfonso was reached by the notice that Clement VII had decided to march on Ferrara. The Duke quickly returned to his own city, which during his absence was ruled by his young son Ercole. Obviously, given the evolution of papal policies and in discontinuity with his loyalty to the French crown, Alfonso set himself up in opposition to the League of Cognac – an anti-imperial pact made between the Pope, Venice and France – and entered into an agreement with Charles V, reinforced by the engagement between Ercole and Margaret, the Emperor’s natural daughter. The Emperor subsequently confirmed to Alfonso the investiture of the lands he held and the appointment of him as captain general of his army in Italy. Thus came the year 1527 and with it the announcement of an armistice between the Pope and the Spanish Viceroy: this infuriated the mercenary troops, who pushed on to Rome, destroying it and plundering it during the terrible ten days of the Sack of Rome. It was Alfonso himself who handed over some artillery from his foundries to the Lansquenets, in particular several falconets (small cannon that could be easily transported). The Pope remained locked inside Castel Sant’Angelo for a long time, surrounded by the Germans without the army of the League succeeding in freeing him, forcing him to retreat to Viterbo and, consequently, to sign a costly capitulation both in economic terms and in terms of possessions, among which Modena was also included. Within a day of this agreement, Alfonso returned to Modena and a few days later the city negotiated a peaceful surrender, returning after 17 years under Este rule. There were great celebrations both in Ferrara and Modena where the Duke stayed for some time to restore his power. To celebrate the moment, Ludovico Mazzolino painted for Alfonso the ‘Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple’, now in England at Alnwick Castle in Northumberland. Alfonso did not return triumphant to Ferrara until 14 June, where he also found his companion Laura, who in the meantime had become the mother of a child named Alfonso a few months before.

Carlo V: Modena returns to the Este family

When the French army descended on Italy to liberate the Pope, Ferrara found itself in the strategic position whereby, in order to reach Rome, one had to pass through the Este Duchy: the pressure for Alfonso to join the League of Cognac was strong (in fact Ferrara had always supported the King of France until then and the marriage between Ercole and Renata of Valois on 28 May 1528 confirmed this alliance) and the fear of losing Reggio and Modena again persuaded him to grant free passage, thus obtaining the Pope’s renunciation of the territories of Modena, Reggio, Brescello and Castello di Novi. The people and his collaborators, however, were not content to take up arms against Carlo V, who had done the Duchy only good. Moreover, the suspicion that Clement VII still wanted revenge for what Alfonso had done at the Emperor’s side, became a reality when the Pope became free again and asserted that he would not sign that treaty, because it was signed while he was surrounded at Castel Sant’Angelo. Clement VII, in practice, absolutely did not want to leave those territories to the Este family. A will also confirmed in front of Carlo V himself, by now dominus of the Italian chessboard, as well as the European one, with whom he started an intense diplomatic relationship to reach peace and face, this time together, the religious insidious, the Protestants, and the threat at the borders, the Turks. A new alliance was sanctioned by the coronation in Bologna of Carlo V, who received from the hands of Clement VII the crown of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Alfonso was forbidden to attend the investiture ceremony, but not to meet Carlo V separately, which he did, precisely to guarantee himself an ally in the future and very difficult negotiations with the Pope. The negotiations were conducted between Clement VII and Carlo V: the first pretended all the territories including Ferrara, but the intervention of the second led to a compromise that postponed the question of the possession of Modena, Reggio, Rubiera and Ferrara to an imperial arbitration. This first agreement satisfied Alfonso, who however already imagined a costly epilogue, at least financially. And so it was, in fact, after a further postponement, the Emperor finally sanctioned the position of Modena and Reggio in favour of the Duke, who, however, would have to redeem them from the Pope with the payment of one hundred thousand gold ducats. What remained was the prohibition to extract salt from Comacchio and the obligation to go to Rome to personally ask for forgiveness in the presence of Clement VII. The sentence did not find favour with the Pontiff, who refused the payment and agreed to invest only Alfonso with the title of Duke, but not his successors. The tug-of-war lasted for another few months, with a failed attempt by the Pope to recover his territories, concluding with the reacquisition of Modena, confirmed imperial feud granted to the Este. Ferrara, on the other hand, was recognised as an ecclesiastical estate that the Pope granted to the Duke and his descendants, provided they showed loyalty and paid a fee. The plan to unite Ferrara and Modena under the House of Este, after years of attempts, was finally realised. Alfonso could then start planning his succession.

Ercole II, the chosen heir

Having resolved the issue with the Pope and the Emperor, Alfonso was able to devote himself more to his family: on 1 January 1530, with a donation deed, the relationship with Laura Dianti was legally sanctioned. At the time she was expecting their second child, who was born on 17 September 1530 with the name Alfonsino.

At the end of August 1533, Alfonso then made his will naming Ercole universal heir of all his movable and immovable property. In the document he also included the children he had with Laura: if the line of Borgia succession died out, they could take over the leadership of the Duchy. To Renata of Valois, his affectionate daughter-in-law, he entrusted the protection of the entire family. In July of the same year, Ludovico Ariosto, the Duke’s collaborator and friend, died.

Even in the last years of his life, however, Alfonso dedicated himself to fortification works, in this case those of Modena: a great physical and economic effort, since Clement VII would never give up the idea of owning Modena and Reggio. But this time too, the Pope’s death came before he could again take action against Alfonso. With the pontiff’s death on 25 September 1534, the spectre of war also receded, the more optimistic scenario was confirmed by the election of Paul III, born Alessandro Farnese.

A month later, Alfonso, seriously ill, died. Before leaving, to confirm the love that bound him to his faithful Laura, Alfonso gave her the Delizia del Verginese.

The Duke died on the evening of 31 October 1534 and the funeral was celebrated on 3 November: the body paraded through the city of Ferrara to the Corpus Domini monastery. He was succeeded, as expected, by his son Ercole, fourth Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio.

Alfonso I and the art

The ‘flaring grenade’: the emblem of Alfonso I

The personal coat-of-arms that identifies Alfonso is the ‘granata svampante’ represented by a sphere from which flames come out through three holes (two on the sides and one in the centre), testimony to the power achieved by the Este artillery and the Duke himself. The motto on the insignia was written by Ariosto, initially in Latin ‘loco et tempore’ and later converted into French ‘A lieu et temps’ and means ‘at the appropriate place and time’, as to be effective, the bomb must explode in the right place and at the right time. The invention of this object used in battles is owed to Alfonso, who, as already mentioned, was nicknamed ‘prince craftsman’ for the manual skills he possessed, especially in forging metal and inventing new weapons to be used in battles.

The symbol is also present in the Duke’s places, for example in the vanished Delizia di Belvedere, built at Alfonso’s request from 1513 on the island of Boschetto in the middle of the Po and destroyed after the Devolution to build a papal fortress (also demolished in 1865). Here the ‘svampante grenade’ is associated with the symbol of the butterfly placed above the sphere, signifying that the place is not meant to be about war but about enjoyment, in fact the destructive force of the ‘balla svampante’ is subordinated to the delicacy of the butterfly.

Related to the theme of butterflies and presumably to the Delizia di Belvedere is ‘Jupiter Painter of Butterflies, Mercury and Virtue’ painted by Dosso Dossi between 1523-24 and now in Krakow in the Royal Castle of Wawel.

In the painting there are three figures Jupiter on the left, intent on an activity not only intellectual (the birth of butterflies), but also manual (that of painting), from which he does not want to be disturbed. Mercury, placed behind him, protects the god’s otium from the arrival of a harried Virtue, who begs to be heard. In the figure of Jupiter, one can read the representation of the Duke, where in the quietness of the Delizia he finds rest from the political commitments that must wait (the Virtue) before the sovereign’s cultural and creative commitment.

The miniature codex of Alfonso

During the difficult years of the dispute with Julius II, Alfonso commissioned an extraordinary miniature codex known as the ‘Offiziolo Alfonsino’ or the ‘Book of Hours of Alfonso I’. The codex is not only a private prayer book of the Duke, but also a political instrument: in addition to exalting the figure of Alfonso, it is used as a means of defending himself against the accusations made by the pontiff and exalting his religiosity by openly emphasising it. The codex was commissioned in 1505, the year Alfonso became Duke, probably to emulate his predecessors who had left behind two masterpieces such as the ‘Bible of Borso’ and the ‘Breviary of Ercole I’. The execution of the work can probably be dated between 1505 and 1510-12, the result of the skill of the court miniaturist Matteo da Milano. After the Devolution, the codex was transferred to the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, where it remained until 1859 when, following Francesco V’s exile to Vienna, it went on the antiquarian market. Today the codex is divided between the Strossmayerova Galerija in Zagreb and the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon.

The first pages of the manuscript are dedicated to the Roman calendar, with indications of saints, liturgical feasts and practical advice on diet and health. After this first part comes the more devotional section, that of the Liturgy of the Hours, which determines the times and moments dedicated to prayer during the day.

The first miniature page (Page c. 13r, Lisbon Museu Calouste Gulbenkian) puts the figure of the Duke in extraordinary prominence: in the upper part, the most famous of the images is depicted, namely the ‘flaming grenade’, and the gold-ground frame is a triumph of coloured flowers, birds, strawberries, pearls, gems and cameos. In the centre the Duke is portrayed in armour with his bearded face marked by fatigue, turned in prayer towards God who appears above him. On the opposite side are his titles in gold lettering on a blue background ‘AL (FONSUS) DUX FERRARIAE III’. The text accompanying this image is the believer’s supplication not to be abandoned in adversity by the Lord and to be protected from the wicked. The meaning of this supplication may mask an allusion to the tensions with the Papal States and in particular with Julius II. The page closes with the Este insignia placed between two fantasy phytomorphic figures.

On the subject of confrontations with the pontiff, the most clearly polemical page is the one with the depiction of the Triumph of Death preserved in Zagreb (Page S.G. 352, Triumph of Death, Zagreb Strossmayerova galerija). Death, personified by a skeleton armed with a bow, arrows and a very long sickle, is intent on reaping victims and is depicted at the very moment when she manages to rest a hand on the pontiff’s shoulder. The Pope, who turns his eyes to Death, is depicted in profile and a beard is visible on his face. It is precisely this characterisation that could allude to the one Julius II had grown as a vow in October 1510. By that time Julius II had excommunicated Alfonso, interdicted Ferrara and personally led the ecclesiastical troops in battles against the Duchy, only his death in February 1513 stopped his advance.

The women in the life of Alfonso I

Three women were part of Alfonso’s Life: Anna Maria Sforza his first wife, Lucrezia Borgia his consort in his second marriage and his last companion, Laura Dianti. Through the portraits of the most important artists of the time, their faces have come down to us, even though the debate over attribution remains animated.

Anna Maria Sforza

The image of Anna Maria Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan Galeazzo Maria Sforza, has not been passed on to us with certainty during the seven years she spent at the Este court. There are several presumed portraits of the lady, the one that meets with the most favourable opinions on identification is ‘La Dama della reticella di perle’ by Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis exhibited at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan. However, we find her depicted on a precious graffito ceramic parade plate, preserved in the British Museum in London. In the centre are two figures: the young man holds a long sword, while the lady holds a lute in her hands; the shield placed at their side identifies them, inversely represented to the figures is the Sforza coat-of-arms and the ‘granata svampante’.

Saint Lucrezia

The iconography of the figure of Saint Lucretia of Mérida is very rare and the painting by Dosso Dossi, official court painter from 1514, can be considered as a tribute commissioned by Alfonso to the late duchess. The dating of the painting is still a debated issue. While some experts point to around 1516, a time when Lucrezia was still alive, others point out how certain elements can be related to a funeral event. The most significant element found to corroborate this hypothesis is the statue in the niche behind the Saint, in fact the object is depicted from behind, so that the observer cannot see her face, this would suggest a depiction of a “mourner”, i.e. a figure marking her passing from the world of the living to the world of the dead. The identity of the Saint is not in doubt, as she points with her hand to the inscription in gold letters ‘S. LUCREZIA’. The painting would be a pendant together with St. Paola (private collection), on which critics once again disagree, proposing Battista Dossi as the author. This second painting, probably executed a few years later, would be a homage to the Duke’s new companion, Laura Dianti, also called Eustochia. It is precisely this name that links the figure of Laura with the daughter of Saint Paola, who was called Eustochia.

Laura Dianti

The best known portrait of the beautiful common woman who became Alfonso’s companion is certainly the one painted around 1523 by Tiziano, now in the Kisters collection in Switzerland. Numerous copies of the painting were made, with critics agreeing that the one in Switzerland is the original, a replica is kept in the Galleria Estense in Modena, others are in the Metropolitan in New York, the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, the Galleria Borghese in Rome and in private collections.

The woman is dressed in blue, wearing a rich dress and her hairstyle is adorned with an elegant diadem. Her expression is elusive, her eyes are not directed at the viewer, but seem to follow a thought or something happening around her. Her central figure fills the space of the canvas, but she is not portrayed alone: in fact, Laura rests a hand on the shoulder of a small African page.

Alfonso triumphant: the Battle of Polesella

The Battle of Polesella, which saw the victory of the Este army over the Venetian fleet, is one of the most important military successes achieved by Alfonso. We find it painted behind the shoulders of the Duke in the painting by Battista Dossi ‘Portrait of Duke Alfonso I d’Este’ now in the Galleria Estense in Modena. The Duke depicted in armour wears the collar of the Order of St. Michael on his chest and rests his right hand on the mouth of a cannon, placed behind him, to emphasise his military virtues, his passion for artillery and great expert in military technique. In the background, the scenes of the battle are painted: above a hill and along the river banks the Este artillery is arranged, infantrymen and cavalrymen are on the battlefield and on the Po the Venetian ships are in flames destroyed by gunfire.

Este artillery was, at the beginning of the 16th century, famous throughout Europe because it was technologically the most modern and efficient, and together with military technique was the protagonist of the victory of Polesella. Ludovico Ariosto, in the 9th canto of Orlando Furioso, describes firearms as terrible instruments “…o maledetto o abominioso ordigno…” because they eliminate the heroism of knights, but he gives us two names of these famous arquebuses that evoke their recklessness ‘Terremoto’ and ‘Gran Diavolo’.

Alfonso’s treasure chest: i Camerini di Alabastro (the ‘Alabaster Chambers’)

The building arm known as the ‘Via Coperta’, built by Borso d’Este to connect the Palazzo di Corte to the Castello Estense, was raised by Alfonso under the direction of Biagio Rossetti, further enlarging the spaces for the life of the court in 1507 with the arrangement of the ‘Camerini d’Alabastro’. These were two consecutive rooms that were used to house the Duke’s art collections before they were dispersed.

As a consequence of the Devolution of Ferrara to the Papal State in 1598, Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, nephew of Clement VIII, immediately ordered the despoiling of Alfonso’s ‘Camerini d’Alabastro’, depredating and taking the works to Rome.

The first ‘Camerino’ must have been under construction between 1507 and 1511 and housed the marble reliefs by Antonio Lombardo, now in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. It was probably only after 1513 that the planning of the second Camerino began, where works with non-religious themes commissioned from the most important living painters were placed. On the walls were Tiziano’s paintings ‘Bacco e Arianna’ (now in London at the National Gallery), ‘Offerta a Venere’ and ‘Gli Andrii’ (both in Madrid at the Museo del Prado), Bellini’s ‘Il festino degli Dei’ (now in Washington at the National Gallery of Art). Dosso Dossi executed a frieze with ten scenes of episodes from the Aeneid, and today four sections have been identified: one in Ottawa at the National Gallery of Canada, one in Birmingham at The Trustees of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts – University of Birmingham, two in a private collection in New York, and one part probably identified in Washington at the National Gallery of Art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

L’età di Alfonso I e la pittura del Dosso: Ferrara, Palazzina di Marfisa d’Este, 9-12 December 1998: proceedings of the international study conference [promoted by the Institute of Renaissance Studies of Ferrara]. – Modena: F.C. Panini, 2004.

Vincenzo Farinella “Dipingere farfalle: Giove, Mercurio e La virtù di Dosso Dossi: un elogio dell’otium e della pittura per Alfonso I d’Este” – Florence: Polistampa, 2007.

Vincenzo Farinella “Alfonso I d’Este: le immagini e il potere: da Ercole de’ Roberti a Michelangelo” with the “Cronistoria biografica di Alfonso I d’Este” by Marialucia Menegatti and the “Pulcher visus” by Scipione Balbo, edited by Giorgio Bacci – Milan: Officina Libraria, 2014

“Libro d’ore di Alfonso d’Este Offiziolo alfonsino” – Il bulino, Milan: Y. Press, 2004

Luciano Chiappini “Gli Estensi: mille anni di storia” – Ferrara: Corbo, 2001

Treccani Bibliographical Dictionary