Although his rule was very long, thirty-eight years, and coincided with an equally long period of peace, Alfonso II went down in history as the last Duke of Ferrara. The absence of an heir to his succession, constantly sought through three marriages, effectively interrupted the Este dynasty, allowing the Papal State to claim the territory of Ferrara upon Alfonso’s death in 1598.

A government officially without war, but characterised by an equally costly ‘battle’: the question of ‘precedence’ against Cosimo dei Medici. It was an enormous burden for the Ferrara state treasury, on which also weighed a vast phenomenon of corruption and squandering of public money by the ministers closest to him, in addition to the huge expenses for the violent earthquake of 1570, all factors that led to a real financial crisis. These circumstances increasingly weakened the government of Alfonso II, making the Devolution of Ferrara inevitable at his death, given the absence of heirs.

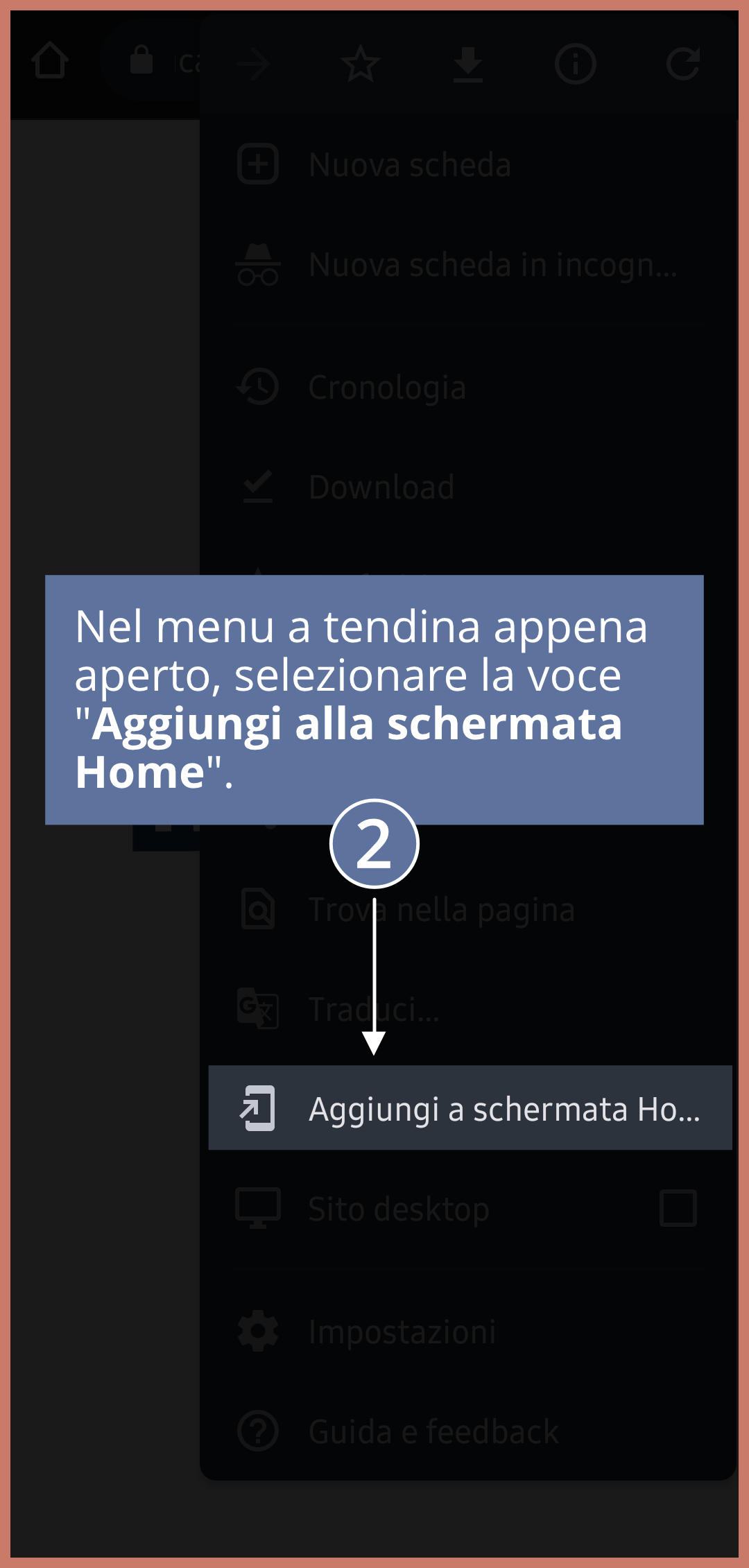

Nevertheless, life at the court of the last Duke of Ferrara was magnificent, characterised by sumptuous banquets, theatre and various shows. Men of letters and artists were welcomed here, including Giovanni Battista Guarini, Torquato Tasso and Pirro Ligorio. Not to mention that it was during this period that the ‘Concerto delle dame’ was created, which confirmed Ferrara as a renowned musical centre and was imitated in many Italian and European courts, a recognition of the value of the city and the Este court.

The Life

Alfonso was born in Ferrara on 22 November 1533 from the union of Ercole II and Renata of France, the daughter of King Louis XII. His childhood passed quietly, following the rules expected of a young prince’s education, between literary and chivalric instruction: Alfonso knew Latin and French, loved hunting, jousting and feasting. Among his youthful passions was also that for war: disobeying a paternal order, for example, at the age of 18 Alfonso had fled to France to his cousin, King Henry II, and, at the head of a company of knights, had distinguished himself in battle for bravery and courage.

Three marriages in search of an heir

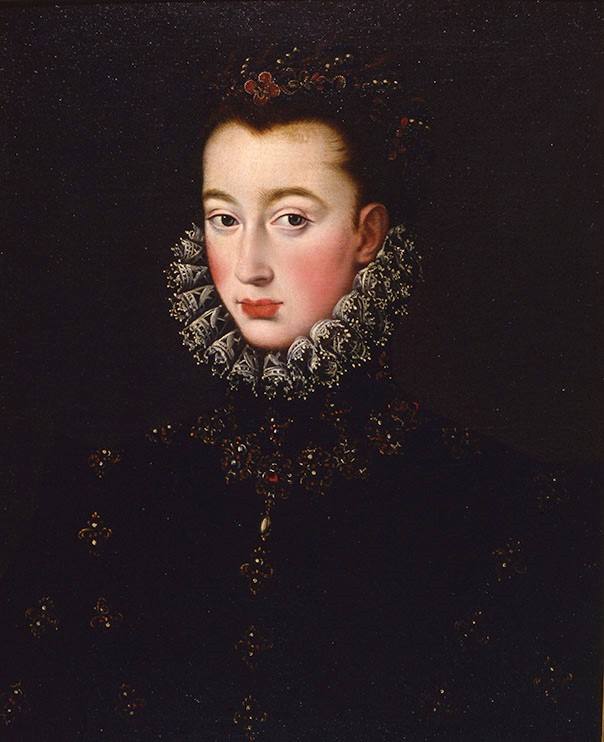

Marriage was always a complex matter for Alfonso II: as is well known, although he had three wives, none of them succeeded in providing him with the indispensable heir the Duchy needed.

The first marriage was to Lucrezia de’ Medici: it had been arranged in the immediate aftermath of the new alliance between Ercole II and Cosimo I dei Medici, who had been the mediator in the peace agreement signed between the Este duke and the Spanish king Philip II.

Although he was not really enthusiastic about his father’s choice, Alfonso married Lucrezia in the chapel of Palazzo Vecchio in Florence on 3 July 1558 to consolidate the alliance with the Duchy of Florence. After the customary festivities, Alfonso hurried back to the battlefield, following Henry II’s army, but above all he returned to the French court, where pastimes were numerous and pleasant. Only the death of his father forced him to return to Ferrara, staying in Florence, at his wife’s, in November of the following year.

The status of first-born son, already designated by his father as his successor, meant that Alfonso’s rise to power was little more than a mere formality. The Duchess Lucrezia arrived in her new city during the carnival of 1560, immediately showing signs of poor health, so much so that in April 1561 she died very young of a pneumonic infection.

The ‘right of precedence’ and the competition with the Medici

Lucrezia’s death was a death with twofold consequences: if on the one hand it had ‘freed’ Alfonso from an unwanted obligation, on the other hand it also sanctioned the rupture of relations between the Este and the Medici, immediately causing strong resentments to re-emerge between the two families over the question of the right of ‘precedence’ in official ceremonies. Both houses, in fact, evoked to themselves the right of precedence, which would demonstrate the greater importance of one over the other. The issue dragged on since 1541 and, after several solutions that did not agree with everyone, it was not until 1564 that the new Emperor Maximilian II was called in to settle the matter, who, as usual, found agreement in two marriages contracted for political purposes. The solution on paper seemed simple and effective: Alfonso was to marry Barbara, while Francesco dei Medici was to take Giovanna as his wife, both daughters of Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg. Both weddings were supposed to take place in Trento, on the same day, but the whole thing was postponed due to yet another quarrel over who had precedence in the ceremony: Maximilian II was therefore forced to postpone and impose that they take place in their respective cities.

The second wife: Barbara of Austria

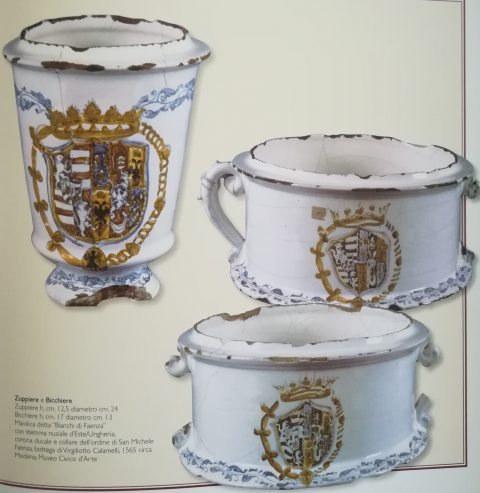

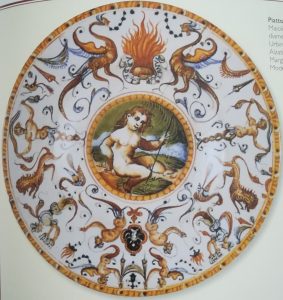

As stipulated by Emperor Maximilian II, Alfonso and Barbara of Austria were married in Ferrara on 5 December 1565. To celebrate the new marriage in the best possible way, the Duke commissioned a workshop in Faenza to create an entire set of majolica, consisting of plates, bowls, soup tureens, pourers and other tableware. The crockery created for the occasion was decorated with the polychrome coat of arms of the Este-Hungarians, surmounted by the ducal crown and surrounded by the collar of the Toson d’Oro. Fortunately, some of the pieces that made up this service have come down to us: two tureens and a small vase are preserved in the Museo Civico d’Arte in Modena, while another tureen is in the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza.

The opulence displayed on the occasion of the wedding remained constant throughout the celebrations, the high point of which was reached on 11 December, when the ‘Triumph of Love’ tournament took place: a grandiose chivalric performance lasting eight hours, which managed to impress all the spectators, including Torquato Tasso, who had come to Ferrara for the first time in the service of Cardinal Luigi d’Este, Alfonso’s brother. But it did not end there: the Cardinal had, in fact, organised a sumptuous banquet for the following day at his residence in Palazzo dei Diamanti: an event of which the precious testimony of the scalco Giacomo Grana remains, who gave a precise description. The quantity and variety of food was impressive: it ranged from freshwater fish brought in from the lakes of Garda and Iseo to saltwater fish; there was no lack of fruit and vegetables such as artichokes, cardoons and broad beans (even though it was December), and the inevitable meat, including wild boar, hares, roe deer and even peacocks, pigs and birds. An example that gives a good idea of the size and sumptuousness of these banquets is the fact that Grana had ten thousand oysters bought for the occasion. It was always the task of the scalco to provide ornaments and musical entertainment: the hall was decorated with flowers, especially carnations, and festoons of foliage and citrus fruits. Unfortunately, the sudden death of Pope Pius IV, born Giovanni Angelo Medici di Marignano, on 9 December forced the couple to cancel the banquet and Alfonso was practically obliged to urgently go to Rome to begin diplomatic activities in favour of his Duchy, pending the election of the new Pope.

These costly activities contributed to further aggravating the situation of the ducal treasury, and Alfonso was forced to impose new taxes to try to improve the situation. Obviously, these new taxes created a wave of strong discontent among the population.

Moreover, even the second marriage was destined to last only a few years: in September 1572, Barbara died of tuberculosis. In the same year, her uncle Ippolito II, the powerful Cardinal who had chosen to live in Tivoli where he commissioned Pirro Ligorio to design the Villa d’Este with its extraordinary Italian garden, also passed away.

The third wedding and the prophecy of Nostradamus

The financial situation of the Duchy soon became unsustainable and to this was added the bull of Pius V, born Antonio Ghislieri, forbidding the investiture of ecclesiastical feuds to illegitimate children (1567) and the earthquake of 1570: a combination of negative events that increased the discontent of the people, making the government of Alfonso II increasingly unstable. In this context and under the watchful eyes of the other courts and his own people, the Duke could not afford to give up the idea of having an heir, going so far as to place his last hope in Nostradamus’ prophecy: ‘By your third marriage and at the age of fifty or so you will have an heir’. So in 1579 he married the very young Margherita Gonzaga, daughter of Duke Guglielmo, in an attempt to finally become a father, but also to strengthen the ancient alliance between the two families.

Again, the celebrations were fabulous. Of the fantastic banquet, we are left with the marvellous pieces of another porcelain set Alfonso commissioned from the Urbino workshop of Patanazzi: plates, cups, jugs, saltcellars and other items that decorated the table. Today, these ceramics are kept in museums and private collections all over Europe and can be traced back to this marriage thanks to the inscription painted on them: each ceramic is decorated with the motto ‘Ardet Aeternum’ and the design of a flame, representing the fire of love that eternally burns. This insignia was also used on other occasions, but historians agree on its attribution: in fact, it is the same as the one on the reverse of a commemorative medal made on the very occasion of the Este-Gonzaga marriage.

Mistakes in foreign and internal policy

Being at the head of a small state, the Este had to constantly reassert their strength, flaunting magnificence through the commissioning of precious works of art, e.g. the Bible of Borso, or grandiose architectural and territorial works, such as the Addizione Erculea and the numerous land reclamations, in order to maintain a position of supremacy and obtain respect, both from the people and from other states. The Este rulers were always able to balance this aspect, essential for their survival, with proper public and financial administration. But with Alfonso II things were different: his personal ambition to appear grandiose drove him to make choices that would prove disastrous for the Duchy.

Alfonso’s desire for prestige and popularity, as we have seen on the occasion of his second marriage, drove him to spare no expense, even to the detriment of the state. The same motivations induced him in 1566 to support the Emperor Maximilian II in the war against the Turks, a choice that turned out to be futile and costly: leading his army he had arrived at the imperial camp near Raab in Hungary, when he was informed of the armistice agreed upon by the Emperor following the death of Suleiman II, with the consequent withdrawal of the troops. The expedition was therefore nipped in the bud and Alfonso had to count the numerous losses of soldiers during the long march through the Hungarian campaign and the squandering of resources, while in return he only obtained the Emperor’s gratitude. The most dangerous threat to the Duchy of Ferrara, however, came from elsewhere and had distant roots, in the war initiated by Alfonso I and Julius II. The Papal State had never abandoned the idea of regaining possession of the territory of the Estense Duchy and Alfonso I had already fought with all possible strength and diplomacy to stem the expansionist ambitions of the Papacy. This time the situation did not involve war, but depended on a personal and physical condition of Alfonso II himself: impotentia generandi. Ferrara was in fact granted as a vicariate and if the Duke had no heirs, it would revert to the Papal States. Alfonso II’s sterility was a known condition and was apparently congenital and not attributable to the fall from a horse in France, a version that was commonly accepted by all. It was on these assumptions that Pius V moved, issuing a bull in 1567 in which he instituted a prohibition against the investiture of ecclesiastical feuds to illegitimate children. In fact, even without naming him directly, the Duke was put with his back to the wall: on the one hand he was childless and on the other the branch of the Marquises of Montecchio, that of Laura Dianti, was considered illegitimate because the marriage with Alfonso I in articulo mortis had never been recognised by the Church.

The rivalry with the Medici was revived again when in 1570 Pius V granted Cosimo the superior dignity of Grand Duke and the title of Most High and Most Serene: this recognition embittered Alfonso II deeply and personally, as Cosimo was also about to become a father.

Two years later (1572) Alfonso travelled to Rome to pay homage to the new Pope Gregory XIII, born Ugo Boncompagni, and took the opportunity to convince him to grant him the right to nominate an heir to succeed him in the dominion of Ferrara. The Pope, however, could not grant the request because it was in opposition to what was sanctioned by Pius V’s bull. A denial that was the prelude to another disappointment: in 1574, in fact, the imperial court did not validate his title of Highness and Serene and Duke of the First Class obtained from Emperor Maximilian II. Alfonso’s desire for redemption did not stop and in the same year he proposed to become king of the Kingdom of Poland, entrusting the knight and poet Giovanni Battista Guarini with the task of carrying out the ambassadorship on his behalf. There were in fact many pretenders to the vacant throne of Poland and initially some rumours gave Alfonso as one of the favourites, but contrary to expectations, the governor of Transylvania came out the winner. This umpteenth failure tarnished the figure of Alfonso II in the eyes of the people and the other courts, who considered him inconclusive and frivolous, wasting time on feasts and tournaments.

The opportunity for a ransom presented itself to him shortly afterwards, when in January 1576 a Caesar’s diploma officially recognised Cosimo I with the title of Grand Duke: the protests of the Gonzaga, Farnese, Savoy and, of course, Este families arose against this choice. The four houses decided to unite in an alliance that would make them stronger and the best way to consolidate a coalition was, once again, to resort to political marriages. It was on this occasion that Alfonso II married Margherita Gonzaga, almost thirty years younger. Only, not even the celebration of this third marriage was sober, weighing heavily on the public finances and, above all, once again raising citizen discontent.

Moreover, during the last years of his rule, Alfonso, by then resigned to the inevitable fate that was about to come upon the Este family, left very delicate decisions and tasks in the hands of a few ministers, often corrupt, who cheated the duke and burdened the people with taxes, putting them in more and more difficulty. Although the Duke knew the gravity of the situation, he did not take a position in favour of his citizens. On the contrary, he managed to worsen the situation with inconsiderate and eccentric acts: for example, he banned hunting, going so far as to prohibit the cleaning of canals so as not to disturb the animals.

The revenge of Lucrezia d’Este

The acts and decisions taken during these last years of government caused a weakening of the fondness of the people of Ferrara for the Este family, who began to lose the fundamental popular support, which they had never lost, especially during the hardest periods. Even within the family itself, ties had become very fragile and it was an episode of violence that would mark the story forever.

The central figure in this story is Lucrezia, Alfonso’s sister, who married Francesco Maria della Rovere, the future Duke of Urbino. It was an arranged marriage, like many others, but with one substantial difference: Francesco Maria was a young prince of just twenty years old, while Lucrezia was already a woman fifteen years older than him. Right from the start, many differences emerged in the couple and Lucrezia soon left Urbino and returned to her own city, where she found the requited love of Earl Ercole Contrari, captain of the Cavalry of the Ducal Guard. Their relationship was revealed to Alfonso II, who did not hesitate to give orders to kill his own captain to avoid any political disagreements with Urbino. Ercole was set a trap: called to the castle to meet the Duke, he was caught from behind and strangled. To conceal the murder, he was then laid on a bed and, faking an attempt at rescue, his death was attributed to an apoplectic stroke. Lucrezia, however, learned the truth and, abandoning the idea of happiness, with a broken heart, swore revenge both on the Duke, who had ordered the execution, and on her uncle Don Alfonso, the one who had informed him. Lucrezia knew how to wait and at the moment of Devolution played a fundamental role in the capitulation of Ferrara.

Saving Ferrara without an heir

Alfonso II had not yet resigned himself to the absence of a direct heir and in 1581 even proposed to his brother Luigi to marry Marfisa d’Este, but as he was a Cardinal, a dispensation from the Papal States was required. Although the prelate’s poor health was an unknown factor for the success of the initiative, several exploratory diplomatic missions to the Holy See were undertaken, but, for the umpteenth time, the Pope referred to the 1567 bull of Pius V, deeming the request inadmissible.

The last forces, in seeking a solution, were explicitly dedicated to convincing the Pontiff, to grant a derogation to Pius V’s bull, proposing the investiture of the Duchy to a person to be designated. After skilful diplomatic work at a distance, Alfonso II arrived in Rome in August 1591 to conclude an agreement with Gregory XIV, born Niccolò Sfondrati, but not even at that extremely delicate moment was the Duke able to agree to the solution accepted by the Pope without imposing new conditions. The Pontiff, by means of a ‘motu proprio’ measure, had in fact agreed to designate as his successor Filippo d’Este Marquis of San Martino in Rio, of the ‘Sigismondino’ line (son of Sigismondo d’Este, brother of Alfonso I), but Alfonso changed his mind: he preferred Cesare, of the Montecchio line, and for him he sought to obtain the investiture without, however, specifying who the person was to be. Obviously, placed in this form, the concession was denied him.

The death of Gregory XIV forced a pause in the negotiations, which resumed with his successor Innocent IX, born Giovanni Antonio Facchinetti de Nuce, who, not approving of the hypothesised solution, caused the much sought-after agreement to fade away. The ascent to the papal throne of Clement VIII, born Ippolito Aldobrandini, revived Alfonso II’s hopes since the new Pope was notoriously on good terms with the Este family but, contrary to his hopes, the Pontiff immediately made clear his intention to re-annex the territory of Ferrara to the dominion of the Church, reaffirming the validity of Pius V’s bull.

Having lost the game with the Papal State, in August 1594 Alfonso II had the succession of the feuds of Modena, Reggio and Carpi recognised by Emperor Rudolph II – for a payment of 400,000 scudi – to Cesare d’Este, of the Montecchio line of descent, thus saving the ducal title and part of the territory.

A year later, on 17 July 1595, Alfonso d’Este drew up his will naming his cousin Cesare d’Este, born in 1562 to Alfonso di Montecchio (son of Alfonso I and Laura Dianti) and Giulia della Rovere, and married since 1586 to Virginia, daughter of Cosimo I dei Medici, as his successor and universal heir of his property. In October 1597, the Duke’s health aggravated, so much so that he forbade even his young wife to be near him. However, he managed to make his last political arrangements and died on 27 October 1597.

The solemn funeral of the House of Este was now only a vague and distant memory: after the ritual in the ducal chapel without even a eulogy, Alfonso II’s body was transported to the Corpus Domini church, accompanied only by a few monks.

1570: the earthquake that destroyed Ferrara

On 16 and 17 November 1570, the city of Ferrara was destroyed by a terrible earthquake that caused enormous damage and aggravated the already compromised financial situation of the State of Alfonso II. The chronicles of the time describe a desperate situation: four tremors followed one after the other and the last one caused most of the buildings damaged by the previous ones to collapse; in the meantime, the entire population poured into the streets, seeking safety in the open spaces. The damage was enormous: among the buildings most affected were the cathedral, the Ducal Palace, the castle, numerous churches and monasteries, as well as people’s private homes. In addition, as was also the case with the recent earthquake that struck Emilia Romagna in 2012, sand liquefaction phenomena occurred even then. The population was forced to live for a long time encamped in open spaces, exhausted both by the seismic swarm that lasted with intensity for at least two months, and by the severe weather conditions. The consequences on the economy and people’s health were merciless and led to very difficult years, with many periods of famine.

The Duke and Duchess did their best to help the population, choosing not to leave the city so as to set an example to avoid mass depopulation. They too were forced to live in a tent in the ducal garden during the long Ferrara winter. Such an arrangement aggravated Barbara’s delicate health, but she never failed in her commitment to the people: to help young girls who had been orphaned or abandoned, she founded the Conservatorio delle Orfane di Santa Barbara (St Barbara’s Conservatory of Orphans) at that time and financed the construction of the Chiesa del Gesù (Church of the Jesus). It was in this building that, after his death, Alfonso II had the sepulchral monument built in the apse: it is the only Este tomb in Ferrara that remains in its original location.

Torquato Tasso and Ferrara

Torquato Tasso (1544 – 1595) was one of the greatest Italian poets and men of letters of the 16th century and was already famous when he entered the service of Cardinal Luigi d’Este, brother of Alfonso II, in 1565. The man of letters soon conquered the Court and especially the sympathy of Lucrezia, the Duke’s sister. Returning in 1571 from his trip to France in the Cardinal’s entourage, Tasso then passed among the stipendiaries of Alfonso II, with the task of composing verse. The following years were intense and after composing the pastoral drama Aminta, which was staged at Court, he continued working on his masterpiece, the Gerusalemme liberata, which can be said to have been completed in 1575. From that moment on, however, a period of emotional instability began for Tasso: he sought protection under other patron princes, constantly questioned his own work, but above all, he wanted to submit his work to the scrutiny of the Inquisition tribunal. So obsessed was he with conforming to the principles of the Counter-Reformation, and following his absolution by the Ferrarese one, he even turned to the Holy See. These personal actions and contact with the Papal States on the subject of heresy did not please Alfonso II, especially because of his previous experiences with his mother Renata who had been condemned as a heretic and who, only for love of her son who had become Duke, left the city in 1561. Also for this reason, following the episode of Tasso’s aggression against a servant, Alfonso II was forced to take him to the convent of San Francesco, from where he managed to escape and join his sister in Sorrento. After two years, Tasso chose to return to Ferrara, but on his return in February 1579, he found the Court busy with preparations for Alfonso II’s third wedding and was received coldly. Exasperated by the situation and his nerves, he exploded in insults and offence directed at the Duke and courtiers. For this he was immediately removed and taken in chains to St. Anne’s Hospital, where he was imprisoned for seven years: first in solitary confinement and then with greater freedom. During this time of imprisonment, Tasso continued to write: not only lyrics, but also numerous letters urging his release. During these years, a number of editions of Gerusalemme liberata were published that were not authorised by Tasso, the title was attributed by a publisher and not by the author, an abuse that contributed to worsening his crisis. It was only in July 1586 that Alfonso II agreed to his release and delivered him into the hands of Vincenzo Gonzaga, his brother-in-law.

Tasso’s imprisonment, indeed, gave rise to much debate: the decision to deprive the poet of his freedom was not shared by everyone and even in this case the figure of Alfonso II was tarnished. Critics have proposed different interpretations for an act that seems excessively harsh towards a courtly man of letters: some have seen in it the Duke’s desire not to have the poet removed from the city, others have interpreted the gesture as a solution to put an end to his contacts with the Holy See, so as to avoid the emergence of any pretext against Ferrara.

The culture of Alfonso II: the passion for collecting and the ladies’ concert

The collecting passion that had always characterised the Este family was a common trait also in Alfonso II, who was attracted to statues, cameos, gems, medals, coins and books. It was a passion that was also enhanced by the importance of the names of the court antiquarians he had wanted alongside him: figures such as Enea Vico and later Pirro Ligorio, who often travelled in search of rare and precious works. However, it was probably book collecting that Alfonso II felt most strongly about, confirmed by the purchases of important volumes for the ducal library such as Latin and Greek codices, as well as important miniated manuscripts.

Music also nurtured Alfonso’s passion, especially in the last period of his marriage to Margherita Gonzaga. For his wife, the Duke instituted the ‘Concerto delle dame principalissime’ (Concert of the principal ladies), which became so famous that there was not a person passing through the Estense territories who did not want to hear these musicians. The ensemble consisted of three singers, ladies-in-waiting to the Duchess: these have been identified by historians as Laura Peperara (or Peverara), a singer and harpist from Mantua; Anna Guarini, a singer and lutenist from Ferrara, daughter of Giovanni Battista Guarini; and Livia d’Arco, a singer and viola da gamba player. During performances the three ladies could however also be accompanied by male figures, but only on special occasions, as special as these musical moments themselves were, since they were reserved for the Court and its illustrious guests only: even the musical pieces composed for the occasion were forbidden to the public and kept secret.

The concert created by Alfonso II was also a great success due to the novelty of introducing more voices and instruments such as the viola, lute and harp in addition to the traditional madrigal harpsichord. Thus the ‘Concerto delle dame’, even in the downward parabola of the Este family in Ferrara, managed to maintain the central role of this Court in the field of music and confirm its prestige and fame. Many were the Lords who imitated this spectacle in their courts, so much so that the demand for female musicians increased significantly, at the same time promoting a new role for the female figure.

Even today, one can admire in the Estense Galleries the symbol that more than any other expresses the passion for music in the court of Alfonso II: the Estense harp, which he commissioned for the ‘Concerto delle dame principalissime’. The instrument was intended for Laura Peperara and was made in Rome from 1581, in a workshop in the circle of Giovanni Battista Giacometti: made of varnished maple and pear wood, the harp consists of a double row of forty-nine strings. The subsequent decoration was realised between 1587 and 1589 by Marescotti from Ferrara: the design of the upper friezes is by Giuseppe Mazzuoli known as Bastarolo, while the execution of the same is by the flemish Orazio Lamberti, finally it was gilded by Giovan Battista Rosselli. After the Devolution of Ferrara, the harp fortunately arrived in Modena intact in 1601, where it can still be admired.

The Este Castle: the Ducal Chapel and the frescoes with the Este genealogy

For a long time the Ducal Este Chapel was known as the “Ducal Chapel of Renata of France”, the result of an alleged commission by the French lady, based on the particular decoration without sacred images, as imposed by the precepts of Calvinism followed by the Duchess. Only recent studies and restorations have brought to light new evidence of the real commissioner, who was Alfonso II. In fact, the Duke had the Chapel built between 1587 and 1591, following the earthquake of 1570: it appears as a small casket embellished with polychrome marble, set in gilded stucco frames, concluded by a vault decorated with images of the Evangelists, interspersed with the white eagle, the well-known Este emblem.

The research of noble origins and dynastic celebration were subjects to which the Este gave much importance, especially with a view to propaganda and political reinforcement against the other ruling families. So much so that on numerous occasions the court literati were called upon to write the family tree, so as to link the Este with figures of undisputed value and prestige. During the rule of Alfonso II, as we know, the most passionate discussion concerned the question of precedence over the Medici, i.e. which of the two families had older and more noble origins. Not only was the ‘Historia dei Principi di Este’ by Giovanni Battista Pigna published in 1570 and the family tree compiled by Girolamo Falletti in 1581, but the walls of the courtyard in the Castello Estense were painted with around two hundred figures of members of the Este family. The courtyard had indeed already been used as an illustrated family tree of the dynasty by Ercole II, but Duke Ercole wanted to renew the characterisations of the figures and increase the importance of the lineage. Alfonso II commissioned this grandiose pictorial cycle around 1577 and the probable author was Pirro Ligorio, who had already been in the Duke’s service since 1568: the figures were painted in pairs (father and son or brothers) with their coats of arms. The attribution of the cycle, as mentioned, is uncertain, but a few preparatory drawings of the pictorial undertaking remain, today dispersed in various European collections: in Italy, one remains at the Uffizi in Florence, while most are at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, others at the British Museum in London and finally at the Staatliche Grafische Sammlung in Munich. At the Pinacoteca di Ferrara, however, only a few fragments of these paintings are preserved, making further investigations into their attribution difficult. The preparatory drawings are certainly by Pirro Ligorio, while for the paintings, documentary research leads to the Ferrara painter Ludovico Settevecchi, although 18th century sources attributed them to Bartolomeo Faccini, in collaboration with other artists.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Luciano Chiappini “Gli Estensi One Thousand Years of History”.

Proceedings of the conference “Ippolito II d’Este cardinal prince patron” edited by Marina Cogotti and Francesco Paolo Fiore, De Luca Editori d’Arte;

Francesca Mattei “L’ingresso trionfale a Modena di Alfonso II d’Este e Margherita Gonzaga: architettura e umanesimo tra Gian Maria Menia e Carlo Sigonio (1584)” in ArcHistoR anno V (2018) n. 9;

Enrica Domenicali “La Cappella Ducale del Castello Estense di Ferrara” in “I buoni studi Miscellanea in memoria di Mons. Giulio Zerbini” edited by Alberto Andreoli, 2002;

“Le ceramiche dei Duchi d’Este. Dalla guardaroba al collezionismo” edited by Filippo Trevisani, Federico Motta Editore, 2000;

Giuseppina Finno ‘Women and music in the Ferrara period of Carlo Gesualdo;

Descrizione del banchetto nuziale per Alfonso 2. duca di Ferrara e Barbara principessa d’Austria preparato / Giacomo Grana; con un appendice di una lettera sopra due piatti di maiolica dipinti di Giuseppe Boschini; [edited by the Accademia italiana della cucina delegazione di Ferrara; preface by Gianni Venturi].

Ferrara: S.A.T.E., 1985;

“L’impresa di Alfonso II. Saggi e documenti sulla produzione artistica a Ferrara nel secondo Cinquecento”, edited by Jadranka Bentini and Luigi Spezzaferro, Nuova Alfa Editoriale, 1987.