The Life

Alfonso was born in Modena in February 1634 to Francesco I and Maria Farnese, sister of the Duke of Parma, Odoardo.

At the age of 21, his father concluded a difficult but far-sighted marriage agreement for him that would consolidate the alliance between the Duchy of Este and the Kingdom of France: in 1655, Alfonso married Laura Martinozzi, daughter of Count Girolamo Martinozzi da Fano and Margherita, sister of the very powerful Cardinal Mazzarino. The marriage brought them three children: the eldest son Francesco died a year later in 1658; the following year, Maria Beatrice was born, who, by marrying Giacomo Stuart, would become Queen of England; finally, in 1660, the future Duke Francesco II was born.

In contrast to Francesco I, who had a bellicose and impetuous character, Alfonso IV did not show himself inclined to war. In July 1657, together with his uncle Borso, he led reinforcements to help his father who was engaged in the siege of Alexandria, but apart from this episode, he scarcely frequented the battlefields also for health reasons, as he was prematurely afflicted with gout.

The brief interlude as Duke

Alfonso IV came to power following the death of Francesco I in October 1658: in politics he confirmed the Duchy’s alliance with France and thus the continuation of the pro-French policy conducted by his father. In December of the same year, he received from King Louis XVI the nomination of ‘Generalissimo of the French arms in Italy’ as a sign of gratitude for the loyalty shown, and through this investiture he was legitimised to be part of the league with Venice. Proud of this appointment, Alfonso immediately committed himself to preparations for the military campaign but was secretly advised by Cardinal Mazarin to also pay attention to any proposals from the Spanish ministers in Milan, considering that the war was almost over and Spain and France had come to an understanding. The Cardinal’s shrewd suggestion was listened to by the Duke and, before the war ended with the Peace of the Pyrenees on 7 November 1659, Alfonso accepted an advantageous agreement with Spain: the treaty was signed on 11 March 1659 and included the Duke’s renunciation of the title of Generalissimo of the French army and the restitution to the Spanish of the cities of Valencia and Mortara occupied by Francesco I. In return, Alfonso obtained confirmation of the investiture of the Principality of Correggio, recognition of the right of neutrality in future conflicts and the allocation of the dogana money of Foggia to the sum of more than 30,000 ducats annually.

To maintain the necessary political balance between Spain and France, the Duke decided to send his brother Almerico as ambassador to Paris. Despite his young age – just seventeen – he was already known for his leadership skills and was appointed General Lieutenant by the King to command four thousand French soldiers in the war of Candia. Unfortunately he contracted malaria on the battlefields, dying in 1660 at the age of twenty-one, but for the great skill he had shown and the victories he had won, the Republic of St Mark erected a statue in his honour in the Frari Church in Venice.

The death of Cardinal Mazarin on 9 March 1661 caused serious political uncertainty, as the d’Este family’s most powerful ally at the French court was missing. On the other hand, the death of the Cardinal also brought a conspicuous benefit to the ducal coffers, exhausted by the long years of war: the Duchess Laura received a considerable inheritance of money and jewellery as well as several annuities in France.

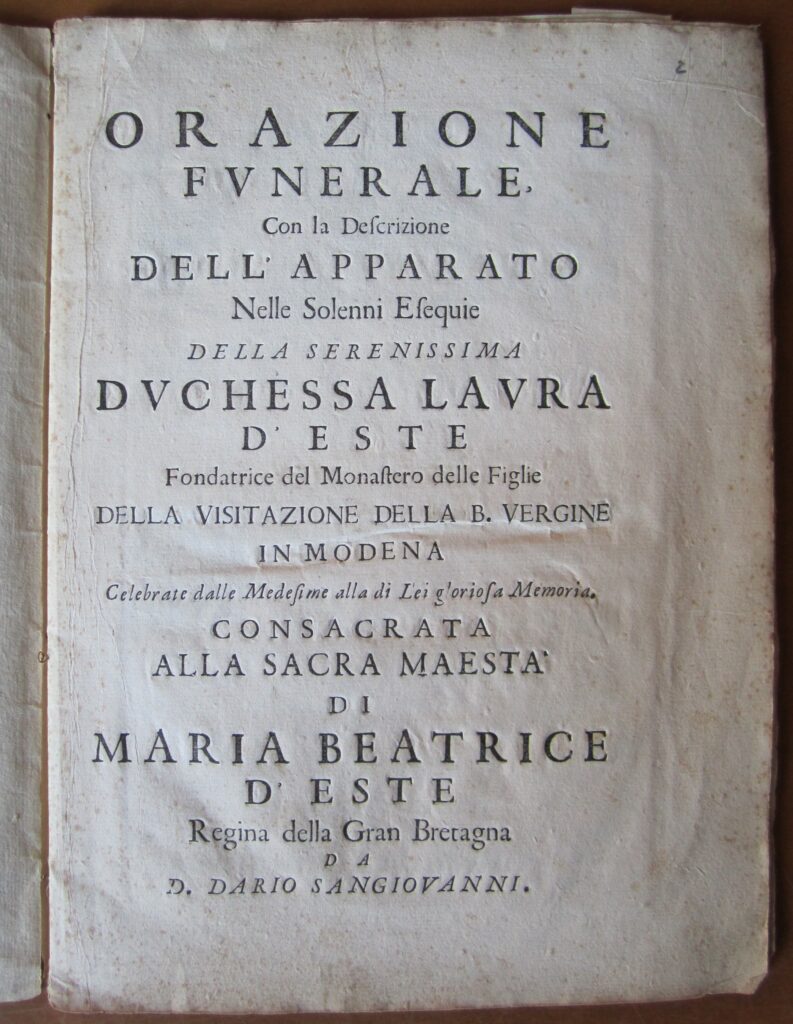

The mourning in the Estense Duchy was not yet over: the Duke’s state of health, already debilitated by illness, worsened, leading to his death on 16 July 1662, at the age of 28. In his will Alfonso IV named his wife guardian of their two children: Laura assumed the regency of the Duchy in place of her son and heir to the throne Francesco II, who was only two years old. On 12 June 1663, the Duchess had a solemn funeral service held for her late husband in the Church of Sant’Agostino, decorated with a new scenographic apparatus that transformed it into the Pantheon Atestinum for the occasion and, as was the case for her father Francesco I, the funeral oration was said by Domenico Gamberti and later printed.

The regency of Laura Martinozzi, a unicum in Este history

In 1622, the Duchess was called to rule the Estense State: at only twenty-three years of age, Laura suddenly found herself having to manage a very onerous position in terms of tasks and responsibilities. In his will, however, Alfonso IV had designated Cardinal Rinaldo as a reference figure for Laura, who had to share with him every information and decision to be made. In addition, she had the support of the Duke’s other brother, Cesare, already General Lieutenant and commander of the ducal militia, a position he maintained until his death in 1662. But the Duchess’ deep Christian faith led her to identify in the figure of Father Garimberti, her confessor, a personal point of reference to whom she referred before making the most important government decisions.

Laura Martinozzi found herself in a very difficult financial situation: the wars undertaken by Francesco I, in addition to the huge sums to finance the passion for art that had united father and son and the expenses for the renovation of Modena and Sassuolo, had drained the ducal finances. In facing this situation and the mournful events that had devastated her life, the Duchess showed such a strong and decisive character that she earned the nickname ‘Duchess Mistress’. She worked to contain the economic crisis, cutting unnecessary expenses and limiting worldly festivities, then, driven by her strong religiousness, she tried to reduce the moral dilemma by imposing the closure of many taverns and increasing penalties for drunkenness.

Contrary to her policy of austerity, she donated conspicuous sums of money for the building of new churches and convents and, blinded by intense faith, made reprehensible choices against the Jewish community that had always found protection in the Duchy of Este. The Duchess consolidated the ghetto in Modena and founded one in Reggio, forbidding Jews from many activities such as pursuing free professions, occupying public offices, preventing marriages with Christians and the possession of real estate. Even in the administration of justice, Laura proved to be firm and resolute, even going so far as to hire assassins to put an end to disputes. During her regency, the acquisition of the two estates of San Felice sul Panaro, acquired from the Pio family in 1669, and Gualtieri, from the Bentivoglio family, is a remarkable fact.

In foreign policy, the Duchess always tried to maintain a position of neutrality by avoiding any kind of conflict, but in front of a personal request from Louis XIV, even if reluctantly, she could not oppose it: the Sun King wanted to place a Catholic princess of his trust at the side of Giacomo Stuart, the future King of England, and for this he chose Maria Beatrice d’Este. Laura’s second daughter was just fifteen years old, while the Duke of York was a grown man of forty: the Duchess tried to oppose, adducing various justifications, but the King of France’s choice was made and impossible to change. The wedding took place in Modena on 5 October 1673, then mother and daughter left the Este city for Paris, where they were magnificently received by the King. They then continued the last part of their journey to London, but not before the English parliament had granted the Catholic princess entry to British territory: finally on 1 December they were received by Duke Giacomo Stuart.

Laura did not return to Modena until May 1674, finding a very different situation from the one she had left: her son Francesco II, during his mother’s absence, decided to assume power of the Duchy, effectively dethroning the Duchess. Laura, surprised and hurt by the emancipation of her son encouraged by her cousins, would from then on play an increasingly marginal role in the government of the Duchy: taking refuge in the faith, she moved to Rome where she died on 19 July 1687 at the age of 48. The following year, the Duke had a solemn funeral celebrated in the Church of Sant’Agostino and, once again, the funeral oration was entrusted to the Jesuit father Domenico Gamberti.

The Pantheon Atestinum

The church of Sant’Agostino, of medieval origins but characterised by a scenographic Baroque interior, was conceived by Laura Martinozzi as the Pantheon Atestinum, the place where the funerals of the Dukes of Modena were held and the glory of the d’Este family was celebrated. On the death of Francesco I (1659), the church was chosen to host his funeral as the simple aula structure, the absence of deep side chapels and the transept made it possible to create an ephemeral architectural apparatus that would act as a backdrop for the funeral rite and exalt the glory of the deceased. Four years later, on the premature death of Alfonso IV, Duchess Laura Martinozzi financed a new funeral apparatus, giving a stable character to the temporary structures built earlier. The sumptuous apparatuses, celebrating the virtues of the Este family, were designed by the Bolognese Gian Giacomo Monti, who had already been at the service of the Dukes of Modena for some years in the designing of ephemeral works, and were rapidly realised between 1662 and 1663 in order to transform the church into the permanent seat of the Este funeral ceremonies.

The structure, commissioned and largely paid for by Laura Martinozzi, consists of walls that are separate and independent from the original church walls (there is a space of about forty centimetres between the two), richly articulated by pilasters and niches and free-standing columns in the presbytery. The materials used are poor (stucco and terracotta for the statues and architectural elements, plastered tiling for the ceiling) but painted white to simulate marble and embellished with gilding. The celebration of the House of Este is entrusted to the representation of a vast series of beatified or sanctified historical figures, partly belonging to the family, partly connected to it according to genealogical links studied by the Jesuit Domenico Gamberti. These links are sometimes fanciful, such as the parentage with Matilda of Canossa, but functional to emphasise the religious virtues of the family, in a Counter-Reformation perspective according to which civil, political, intellectual and military virtues descend from them.

The elaborate iconographic programme designed by Father Gamberti himself is arranged in four orders. The first is represented by the canvases on the side altars, which are no longer in place today and which depicted the saints of the House of Este; The only exception is the canvas, still present in the pseudo-right transept, painted by Francesco Stringa with ‘Saints Monica, Augustine, Thomas of Villanova and Guglielmo of Aquitaine venerating the image of Mary and Child’, which frames, through an oval hole, the 14th-century fresco by Thomas of Modena of the ‘Madonna and Child’, perhaps coinciding with the image of the ‘Madonna of the Belt’ venerated in the Middle Ages in this church. The second order is made up of the statues placed in the niches and the stucco stories: they still represent saints belonging to the family or related to it, with a clear prevalence of women, a fact that can be explained by the commission of Duchess Laura Martinozzi. They are the work of the sculptors Giovan Battista Barberini (statues), Lattanzio Maschio (seven statues in the presbytery) and another sculptor from Barberini’s circle (eight statues of queens and empresses in the nave). The third order consists of the medallions placed in the upper part of the wall: they too are the work of Barberini and represent eight busts of holy kings and four busts of holy Pontiffs. Finally, the fourth order is made up of the figures of saints and blessed painted in the ceiling panels, works by Francesco Stringa, Olivier Dauphin, Sigismondo Caula and Giovanni Peruzzini.

The sumptuous apparatus, despite the poverty of the building materials, remained in place even after the funeral of Alfonso IV and was used again for the funeral of Duke Francesco II in 1695.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Modena Capitale” Luigi Amorth, Banca Popolare dell’Emilia Romagna, Poligrafico Artioli SpA, 1997

“Gli Estensi. One thousand years of history” Luciano Chiappini, Ferrara, Corbo Editori, 2001

“Gli Estensi. La corte di Modena” edited by Mauro Bini, Il Bulino edizioni d’arte, 1997

Claudia Conforti “Architecture legitimises power: Laura Martinozzi (1639?-1687), Duchess of Este and Duke of Modena (1662-1674)” p. 187-198, in “Bâtir au féminin? Traditions et stratégies en Europe et dans l’Empire ottoman”, Paris, 2013

Roberta Iotti “Laura ducissa, Laura dux. Una donna al governo della corte estense”, Quaderni Estensi, Magazine, III, 2011