The Life

Francesco was born in Milan on 6 October 1779 to Maria Beatrice Ricciarda d’Este and Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg-Lorraine, son of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. His birth marked the origin of the Austro-Este line of descent.

He was always firmly opposed to Napoleon’s revolutionary ideas, because of which, as a boy, he experienced the hardships of a life in exile and lived through the death of his paternal aunt, the famous Marie Antoinette, who was executed by guillotine in France in 1793. Following the French conquest, the Este family considered it safer to leave Milan and take refuge in Vienna, where Maria Beatrice Ricciarda did her best to arrange an excellent marriage for her son and the lineage. Having vanished the possibility of marriage to the Emperor’s eldest daughter, Archduchess Maria Luigia, who was to marry the ‘enemy’ Napoleon, Francesco married in 1812 Maria Beatrice of Savoy, daughter of the King of Sardinia Vittorio Emanuele I and Maria Teresa Giovanna (1773-1832), Francesco’s sister, and due to the close relationship (they were uncle and niece) a papal dispensation was required.

The major European powers present at the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) considered Francesco IV of Austria-Este to be an important part of the extensive programme of restoration they had conceived and, with this in mind, again assigned the territories of the Duchy to him. On 15 July 1814 Francesco IV made his solemn entry into Modena amid the celebrations of the population that lasted for days.

The return of the Este family to Modena: the Restoration

On his return Francesco promised the population that he would restore the tranquillity experienced under his grandfather’s rule and, to achieve this, it was necessary to cancel all revolutionary innovations. The Duke immediately revoked the laws of the Napoleonic period by reinstating the Estense Code of 1771, cut anyone who had been employed in prestigious positions during the Kingdom of Italy out of the government administration, established a Council of State (which, however, never met) and abolished the municipal councils. The territory was divided into five provinces: Modena, Reggio, Garfagnana, Lunigiana and Frignano. The first three were administered by a governor, while the others by a delegate; the larger municipalities were governed by a podestà and the smaller ones by a mayor, both assisted by councillors.

The long years of war and the continuous spoliation cost the Duchy a great deal of money and it was faced with a severe famine. The Duke was quick to tackle the situation by banning the export of grain, buying quantities abroad and organising distribution at controlled prices, while the indigent were guaranteed free of charge.

Restoration activities continued with the return to Modena of the Jesuits (1821) to whom schools and colleges were entrusted, while all religious orders were allowed to reopen churches and monasteries. Francesco did his utmost to reorganise public life by re-establishing the University and the Academy of Science, Letters and Arts, setting up gymnastics and swimming schools, and establishing public baths. In addition, during the thirty-three years of his rule, he oversaw the recovery of works of art stolen by the French.

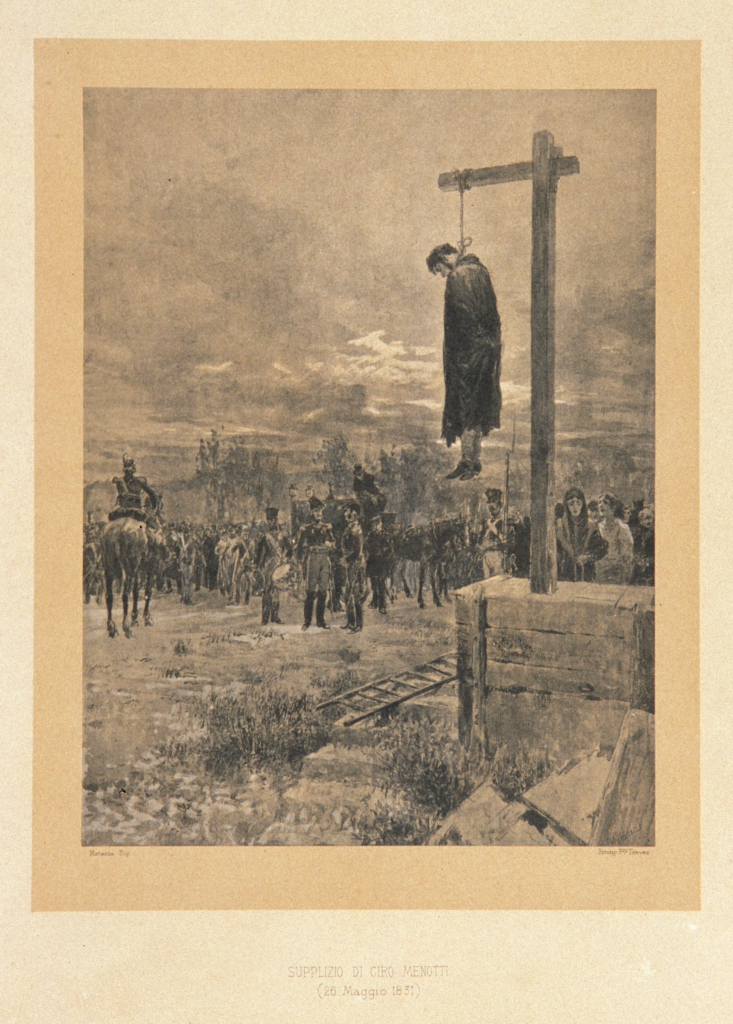

Although the restoration activities carried out by the conservative states had dulled the innovative ideas of the revolution, the flame of change was present in Modena as it was throughout the peninsula, the Carboneria and other secret societies were in fact present in the city. Following the Carbonari insurrection in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the Duke, in order to curb the phenomenon, promulgated an edict on 20 September 1820 declaring anyone affiliated with the Carboneria or similar secret societies guilty of lese majesty, as well as anyone who favoured or failed to denounce such activities, under penalty of death and confiscation of property. Although the southern insurrection was easily suppressed, another one broke out in Piedmont and the Duke, once again, responded to the uprising with an edict instituting a ‘tribunal for public order and safety’, which provided for the replacement of the death penalty by beheading with that by hanging.

There were arrests, trials and convictions including that of Don Giuseppe Andreoli, sentenced to death by the intransigent Francesco IV, who considered the reconciliation of religious and liberal principles inadmissible. A position, that of the priest, further aggravated by the alleged accusation of proselytising his young students. Despite the widespread conviction that the Duke would eventually commute the priest’s sentence, Francesco was rigid and determined to make this conviction an exemplary case, which is why, in the end, the execution was carried out on 17 October 1822.

The Duke’s strategy was not only to repress the liberal uprisings with targeted actions, but he thought about their preventive containment with initiatives aimed at young people to be implemented especially during the university years. To achieve this tight control, in addition to the censorship of the press that was not directly controlled, he set up boarding schools in distant locations where he had the young people distributed, spacing them out so as to minimise possible tumults. The first students to be divided between the boarding schools of Mirandola, Fanano, Reggio and Modena were those from the faculty of law, considered the most politically dangerous, to which the Duke imposed a maximum of twelve graduations each year.

Also with a view to constant surveillance of the young, Francesco IV entrusted middle school education to the members of the clergy, in particular the Jesuits, trusting in the iron discipline that religion would instil in the students.

The insurrection in Modena

Despite the control exercised by Francesco, the flame fanned by the wind of freedom brooded in Modena and would soon flare up, supported by Enrico Misley and Ciro Menotti. The story still shows obscure sides, the objective fact is that the Duke knew both of them, but on what role he played in the event one can only make suppositions, more or less shared and argued. The duke got to know the entrepreneur Menotti in 1823 when he went to see his steam machine for processing silkworms; two years later he publicly congratulated him on the invention of an instrument to refine aqua-vitae and finally, in 1830, in order to avoid the dismissal of his workers, he advanced him a large sum on a free loan. In this situation, it is likely that lawyer Misley, a regular visitor to Ducal Palace and a friend of Menotti’s, intervened between the two. The hypothesis is that Misley, knowing both Menotti’s contacts with the leading exponents of the liberal uprisings and the Duke’s ambition, proposed to the latter a hypothetical war against Austria, bragging about the possibility of ascending the throne of Italy. Following this narrative, Francesco would have agreed to support the revolt, the date of which had been agreed for 5 and 6 February, which would have broken out simultaneously in the cities of Modena, Bologna and Parma. At this point, however, the Duke discovered that the Empire was aware of the insurrection and, frightened by the possible Austrian intervention, pulled out of the agreement, leaving Menotti alone. The latter tried to anticipate the revolt, but on the evening of 3 February his house was surrounded and all the rebels were arrested. The following day the Duke, informed of the coming of the Bolognese insurgents, took refuge in Mantua taking the prisoner Menotti with him, while a provisional government was established in Modena. Thanks to the help of Austrian troops, Francesco returned to the capital after thirty-one days. A trial followed that condemned Menotti and the notary Vincenzo Borelli to capital punishment for high treason, along with 27 other defendants in absentia. On this occasion too, Francesco showed no mercy by signing the two death sentences of the rebels who went to the gallows on 26 May 1831, on the ramparts of the Cittadella.

The Last Years

The following years passed relatively quietly, during which the Duke worked hard on the renovation and improvement of the city.

In 1840, Duchess Maria Beatrice of Savoy died at the Villa del Catajo, while the following year saw the marriage of her son and future Duke Francesco V to Adelgonda of Bavaria.

Not long before his death, in November 1844, the Duke had stipulated the Treaty of Florence with Parma and Tuscany in which the borders between the three states were redefined. Francesco IV obtained from Parma the Duchy of Guastalla and some territories on the right of the river Enza, in return for the territories on the left of the river and the Tuscan territories of Lunigiana, while the Vicariates of Barga and Pietrasanta were ceded to Tuscany. Moreover, for a better definition of the territorial border between the Duchies of Parma and Modena, the two states exchanged some portions of territory along the Enza river, which became the border between the duchies.

After a painful convalescence, Francesco passed away on 21 January 1846 in the Ducal Palace in Modena and was buried in the Church of San Vincenzo following a solemn funeral.

Culture and urban renewal

Francesco IV’s hard conservative will and the policy of control and repression of liberal ideas were the protagonists of his long rule, but he was not insensitive to culture, which he kept away from politics. The Duke did his best to recover some works that had been requisitioned by France, he brought to Modena a series of paintings from the collection of Tommaso degli Obizzi preserved in the Villa del Catajo, left as an inheritance to the Este family in 1802, and he also purchased paintings for the Ducal Gallery. A great pride of his was the conclusion, in 1843, of negotiations to regain possession of one of the most prestigious works, and today a symbol of the Estense Gallery, the ‘Portrait of Francesco I’ painted by Velasquez. He established the Numismatic Museum, endowed the University with cabinets, a scientific library and an astronomical observatory.

Francesco IV did his part in charity work by financially supporting the Institute of San Filippo Neri and, in 1816, when the church of San Paolo was reopened, at the wishes of the Duke and with the protection of Duchess Maria Beatrice of Savoy, a boarding school for poor girls was set up in the monastery.

Dated 1815 is the institution, both in Modena and Reggio, of the Casa di Lavoro (House of Work) where destitute or otherwise unemployed people, about a thousand a day, went to work hemp in return for a meagre payment, in addition to which there was free lunch for all. In the centralising and conservative vision of Francesco IV, the employment of the unemployed, who were given the opportunity to support themselves, ensured him wide popular support. For example, in the winter of 1816, men from the most deprived mountain areas were called in to dig a dock along the Naviglio and their wives were also entrusted with hemp-spinning jobs.

After the Napoleonic interlude, churches and convents were reopened, although in fewer numbers than before, and their use was often changed, as happened in 1830 for the ancient monastery of Sant’Eufemia in which Francesco IV installed the barracks and stables of the Estensi Dragoons, the military treasury and the prisons; the renovation work on the complex was supervised by engineer Santo Cavani. In 1835 he founded the Military School for cadets, open to all. At the instigation of Francesco IV, the reconstruction of the Foro Boario was begun by architect Vandelli, to house the cattle market on the lower floor, which was completely porticoed and passed through, and the granaries and storerooms for foodstuffs on the upper floor. The intention was to redevelop the area of the butcher shops in the city centre and to cope with famine and food shortages. Due to the poor use of the site, it was converted into military barracks in 1854.

The Duke participated in the construction of the New Municipal Theatre that was built in Corso Canalgrande, right in front of Ciro Menotti’s house, to replace the old 17th-century theatre along Via Emilia. The project was entrusted to architect Vandelli, who proposed a neoclassical building that was inaugurated on 3 October 1841 with the opera Adelaide di Borgogna al Castello di Canossa (music by Alessandro Gandini, libretto by Carlo Malmusi). Francesco IV financed the royal box and provided marble from the villa at Tivoli. An epigraph on the façade reads ‘for dignity of the municipality and with the auspices of Duke Francesco IV’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Gli Estensi. A thousand years of history” Luciano Chiappini, Ferrara, Corbo Editori, 2001

“Gli Estensi. The court of Modena” edited by Mauro Bini, Il Bulino art editions

“Modena Capitale” Luigi Amorth, Banca Popolare dell’Emilia Romagna, Poligrafico Artioli SpA, 1997

Treccani Bibliographical Dictionary of Italians