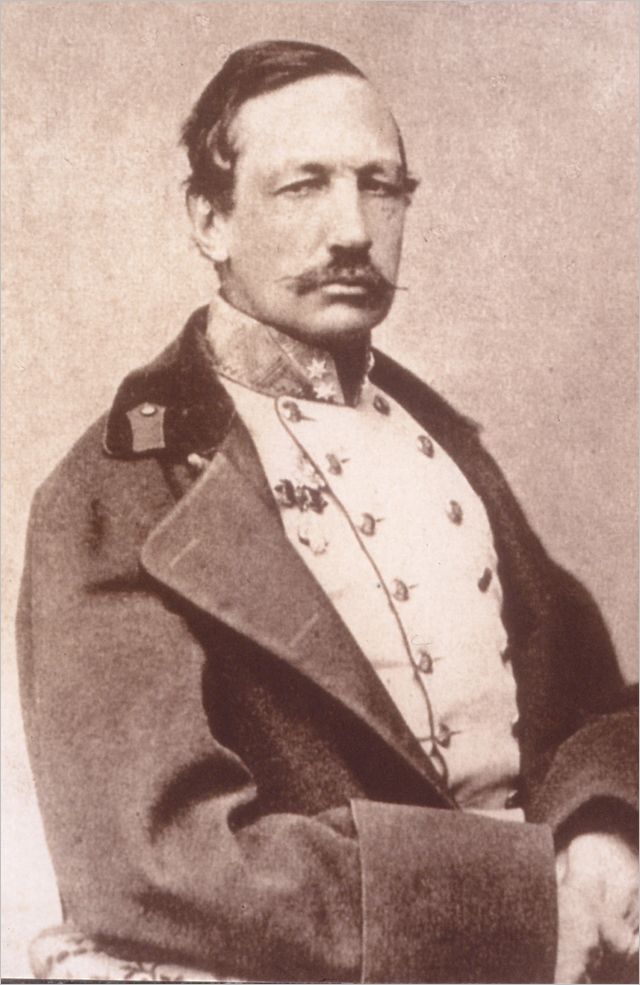

The life

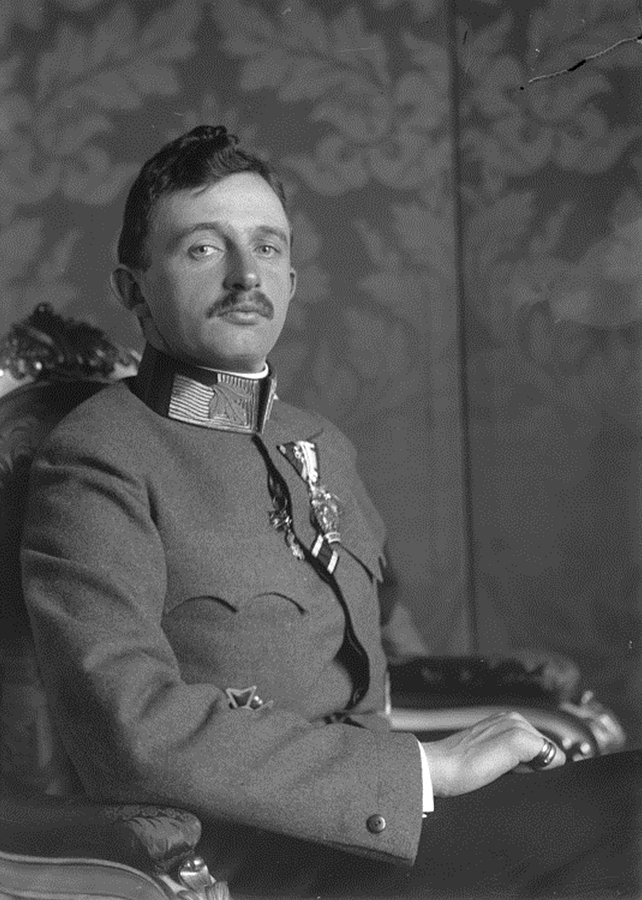

Francesco Geminiano of Austria-Este was born in Modena on 1 July 1819 to Duke Francesco IV and his wife Maria Beatrice of Savoy. In the harsh climate of the Restoration, the young man received an education based on the strict principles of religious faith and his father’s conservative ideas, which led him to firmly believe in the divine authority of the sovereign.

On 30 March 1830, he married Princess Adelgonda of Bavaria, daughter of King Louis I. The wedding took place in Munich and the newlyweds entered Modena on 16 April, warmly welcomed by the population. In honour of the new couple and in the presence of the King of Bavaria and the entire court, the opera ‘Elisir d’Amore’ by Gaetano Donizetti was staged the following day.

Francesco was absolutely convinced that he recognised both Austria and Italy as his homeland, so much so that in 1840-41 he wrote the ‘Plan of an Austrian-Italian Confederation’ in which he envisaged a union of some of the Italian states placed under the Austrian protectorate. The following year he assumed the title of commanding general of the Este troops.

Becoming a Duke: the Treaty of Florence and the Customs League

Following the death of his father on 21 January 1846, Francesco V became Duke and was immediately involved in events of great importance for the state, at a time when the Italian states were preparing for the new wave of revolutionary uprisings of 1848.

In October 1847 the Duke of Lucca, Carlo Lodovico di Borbone, in order to prepare for the succession over Parma and because of the unrest that had broken out in his territory following the liberal uprisings, abdicated in favour of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. This abdication triggered a clause provided for in the Treaty of Florence of 1844, concluded between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio and the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, which also sanctioned certain adjustments to rationalise the borders between the States in the area of Lunigiana and Garfagnana in Lucca.

Francesco V was thus able to announce his taking possession of the Lunigiana territories. The population of Lunigiana asked Grand Duke Leopoldo to remain under his government and the latter, moved by the desire not to exacerbate the discontent of the population, turned to the Duke to ask for the formal suspension of the treaty. Francesco V showed himself resolute and did not renounce what had been agreed upon, demonstrating his strength by sending Este troops to occupy the territories of Gallicano, Minucciano, Montignoso and finally Fivizzano, which did not oppose. Instead, Tuscany’s remonstrances became more sustained, but slowly the waters calmed down and the Este, now in possession of the territories, recalled the ducal troops.

The agreement proposed by Francis V and signed in December 1847, which provided for the stay and maintenance of the imperial troops in the territories of the Duchy, must be seen in this period full of tensions and liberal ferment, in which the support of Austria was fundamental for the Duke. Austria was supposed to reimburse the expenses incurred by Modena for this purpose on a quarterly basis, but the magnitude of these sums and the slowness of the payments, which were deferred over time, soon led to the request to reduce the troops stationed in the territory, leading to their complete withdrawal in 1855.

In August 1849, negotiations were concluded for the free navigation of the river Po and the purchase of the territory of Rolo, against the renunciation of the rights that belonged to the Duchy in the stretch between Brescello and Gualtieri.

The other important issue Francesco V had to deal with was that of the customs league, where his inclination in favour of Austria was still evident. Initially, the request to form a customs alliance came from the Papal States, the Kingdom of Piedmont and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, united in their desire to achieve profitable trade and better transit between the states. Such a coalition, however, could have resulted in a political rapprochement between the states, which the Duke disapproved of, as he was firmly opposed to any liberal opening that might limit his authority. Having ceased negotiations with the Italian states, Francesco V began a laborious negotiation with Austria, which ended in 1852 with a first customs treaty lasting three years, signed by Austria, Modena and Parma. The pact did not benefit the two small states, so much so that Parma left after the expiry date, while the Duchy made a new agreement in 1857 that allowed it to retain its administrative independence and the possibility of making agreements with other states.

The First War of Independence 1848

Once again the winds of change were rising in Italy, prompting the population to rise up against the rulers and demand democratic laws. The first to rise was the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, in January 1848, forcing the King to grant a constitution, while in March the insurrection against the Austrians inflamed Milan and liberal ideas also excited Modena, where small revolts took place that worried the Duke. On 19 March, many young people had gathered between Porta Bologna and the Baluardo di San Pietro for a demonstration that took the name ‘Revolution of the Giunchiglie’ from the white and yellow cockade they wore in their buttonhole, also organised in solidarity with the Hungarian people. The demonstrators were dispersed and the protest was resolved with a few scuffles, but the news of the revolt in Vienna deeply shocked Francesco V, who ordered cannons to be placed in front of the Ducal Palace. During the night, an edict was drafted inviting the citizens to calm down, but the following morning the people took to the streets again, while a popular delegation, headed by the lawyer Giuseppe Malmusi, made a series of requests to the Duke, including the removal of the Austrian troops and the granting of a civic guard. Francesco V did not want to listen to or negotiate with the citizens and left the burden of bargaining to his uncle Ferdinando, who, in order not to heat up tempers further, only agreed to the establishment of a civic guard equipped with three hundred rifles. The joy of the population spread through the streets while from other towns in the Duchy came news of the increasing difficulties in maintaining public order. The situation worsened when a communication from Bologna warned of the imminent arrival of the ‘Alto Reno’ battalion from Bologna to reinforce the insurgents. The unstable situation induced the Duke to leave the state and appoint a Regency Council, issuing an edict in which he promised reforms and amnesty. On 21 March, the Duchess and Archduke Ferdinando left Modena, followed by the Duke, who sadly left the Ducal Palace disguised so that he would not be recognised.

The regency established in Modena immediately fell and a provisional government presided over by Malmusi took office; the same thing happened in Reggio and, at the beginning of April, the two governments united in the ‘Provisional Government of the two Provinces of Modena and Reggio’ which issued a series of measures inspired by democratic ideas and aimed at the welfare of the citizens. The Municipality collected the signatures of those wishing annexation to Piedmont and the formation of a constitutional kingdom in upper Italy; a delegation brought the favourable response to King Carlo Alberto and offered him the territories of Modena, Reggio, Guastalla and Frignano. A few days later (24 June 1848) the King sent a Royal Commissioner, Senator Lodovico Sauli, to Modena and the Municipality dissolved the provisional government. There was still some discontent among the population, as the annexation and the new measures were not accepted by all.

After the important victories won by the people of Piedmont and the allies, the fortunes of the campaign changed dramatically following the defeat at Custoza (27 July), and ended with the armistice of Salasco (9 August 1848), thanks to which Francesco V was able to return to his state. The Duke resumed governing according to his paternalistic and absolutist vision of a power believed to be of divine origin but, despite this conviction, he remained magnanimous and on his return did not carry out violent repressions or death sentences.

It is worth mentioning the assassination attempt that involved the duke in November 1849 when he was near Medolla, returning from a stay in the ducal casino at San Felice sul Panaro. Francesco V got out of his carriage and set off on foot, distancing his entourage. The young Mazzinian Luigi Rizzatti took advantage of this and shot him, intending to avenge the death and imprisonment of so many Modenese patriots. The Duke was unhurt by the attack because the weapon jammed and although the action committed by the young man was very serious, during the trial Francesco did not demand the maximum sentence and the shooter was sentenced to ten years in prison. In the place where this episode occurred, the Duke had a small oratory built between 1856 and 1859 as thanks for having escaped the assassination attempt. It was never completed, nor was it consecrated, so much so that, after the Unification of Italy, it was used as a canton house.

The Second War of Independence 1859

From the Peace of Milan, 6 August 1849, to 1859 the political situation of the Duchy remained crystallised in the position of subservience to the Austrian Empire. During these years Francesco V approved a series of new legislative reforms such as the one on the expropriation of land and buildings for public utility (1848), modernised the civil code and the civil procedure code (in force since 1852), the penal code and the penal procedure code (in force since 1856). Francesco was committed to the renewal of the University: the agreement with the Papal State through which the bishopric of Modena was elevated to archiepiscopal status and the institution of the ‘Provincia Ecclesiastica Atestina’ was no longer subordinated but was joined to that of Bologna is dated 1851. The university, schools, the press and the arts were regulated by strict rules and subjected to strict controls that led to censorship on political, philosophical, religious and moral topics. In 1851 the telegraph was introduced and the following year the first postage stamps of the Duchy were issued, on which the Estense eagle was stamped. A few years later work began on the construction of the ‘strada ferrata’ (railway) that would connect Modena to Reggio; the section was inaugurated on 23 May 1859 with the first journey of the train. In July 1857, Modena received a visit from Pope Pius IX, born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti, who, during his three-day stay, had numerous opportunities to get to know the city, visit the convents and colleges, bless the crowds and officiate at mass in the cathedral.

The situation precipitated in 1859 when the time for national unification was ripe. At the beginning of the Second War of Independence against Austria, Francesco V was the only Italian prince to openly declare his loyalty to Vienna, confirming his devotion to the Empire. If he initially tried to keep the population in the dark about the events and the Franco-Piedmontese victories by flaunting security and tranquillity, he could no longer hide the gravity of the situation when, after the defeat at Magenta, the Empire recalled its troops leaving the Duke unable to resist alone with his own army. Once again, but this was really the last time, the Este abandoned their state: it was on the morning of 11 June 1859 when Francesco V left forever the territories that had belonged to the House of Este for almost eight hundred years. He proclaimed a regency and before leaving he had an order of the day read on the Piazza d’Armi to clarify his behaviour and then, leaving Modena, he reached first Carpi and then Mantua. He was followed by the very loyal ‘Brigata Estense’, which voluntarily did not abandon the Duke during the next four years of exile, only to be disbanded in 1863 in Cartigliano Veneto where, on 24 September, a solemn ceremony was held and all the men were awarded a medal bearing the inscription ‘Fidelitati et constantiae in adversis’ (Loyalty and consistency in adversities). After the official handover of the flags, and at Francesco V’s request, many officers and soldiers took up service in the Austrian army. Once the militia had been disbanded, the last Este Duke retired to the Landstrasse palace in Vienna and then, in 1863, purchased Wildenward Castle in Bavaria, where he and his wife resided.

Following the Third War of Independence, the Emperor of Austria, with the Treaty of Vienna of 3 October 1866, officially recognised Vittorio Emanuele as King of Italy, and this put an end to the various requests for recognition of the rights of the dethroned sovereigns, including those made on several occasions by Francesco V.

During his escape, the Duke had brought with him valuable works of art that he believed belonged to the d’Este family and not to the state. The new government responded to this by seizing the duke’s allodial assets, and these events provoked controversy that continued in court. After several meetings, the parties settled the dispute by signing an agreement in which Francesco returned the movable works of art on the condition that they be kept in the city of Modena and take the name ‘Estense’, keeping for himself three priceless miniature codices, the Bible of Borso d’Este, the Offiziolo Alfonsino and the Breviary of Ercole I.

Francesco was a great lover of travel and during his years of exile in Austria he still had the opportunity to visit faraway places such as the Holy Land and the East. After a short illness, he died without an heir on 20 November 1875 in Vienna at the age of 56. Although he had no descendants, Francesco V appointed Archduke Francesco Ferdinando, eldest son of Archduke Charles Ludwig of Austria and Archduchess Maria Annunziata of Borbonr, Princess of the Two Sicilies, as his universal heir. The designated heir had to accept several conditions and failure to comply with even one of them would lead to forfeiture of the right and use of the inheritance. Among the prescriptions were that he had to take the surname of Austria-Este for himself and his heirs, include the Este coat of arms in his coat of arms, learn to speak and write Italian correctly and, in addition, it was forbidden to marry a non-Catholic princess. However, fate still had surprises in store, because Francesco Ferdinando was assassinated on 26 June 1914 in Sarajevo, a murder that was described in history textbooks as the spark that started the First World War. The Estense inheritance then passed to Archduke Carlo Francesco (grandson of the murdered Francesco Ferdinando) who married Princess Zita of Borbone-Parma in 1911 but, once again, fate had planned a different story. In fact, as Carlo Francesco was also heir to the throne of Austria, following his proclamation as Emperor on 21 November 1916, he lost the right to the Este inheritance, passing on the surname and coat of arms of the Este to his second son Roberto (the Este inheritance was not passed on to his eldest son Otto because he was destined to succeed him as Emperor of Austria). Archduke Roberto married Princess Margherita of Savoy-Aosta in 1953 and their eldest son Lorenzo, born in 1955, currently holds the Este titles. He was married to the Belgian Princess Astrid and has a family of five children, of whom Amedeo, born in 1986, is designated as Crown Prince.

The Duchy after the Este family

After the abandonment of the Duke in 1859, the people forced the weak regency to resign and hoisted the Italian tricolour on the Ducal Palace in Modena. A new five-member council was elected that reconfirmed the 1848 act of annexation to Piedmont. The lawyer Luigi Zini, an exile since 1848, arrived in Modena and was appointed ‘extraordinary provisional commissioner’. With great jubilation from the crowd on 19 June, the delegate of the Piedmontese government, Luigi Carlo Farini, arrived in the city and led the definitive passage of annexation to the Kingdom of Italy. The events, however, were not yet over. In fact, the signing of the armistice of Villafranca on 11 July 1859 gave the deposed sovereigns the opportunity to return to their domains without the support of foreign weapons, while the royal commissioners would peacefully retire. The situation of uncertainty put the city in a state of turmoil, but Francesco V did not give orders to the Estense Brigade and did not move from his exile; likewise Farini took a step back by leaving the position of royal commissioner on 27 July, while continuing his intense legislative activity in both the economic and social fields. On 14 and 15 August, the citizens elected the Constituent Assembly, which had already been in place since 16 August; four days later, the Assembly decreed Francesco V’s decadence and renewed the territory’s union with the Kingdom of Sardinia. Although the will of the population to surrender to Vittorio Emanuele was explicit, the King, limited by treaty, could not accept this request while the European powers were in favour of a new restoration. Following a more moderate line Parma, Piacenza and then Romagna were entrusted to Luigi Carlo Farini who succeeded in achieving a single government in the territories of Emilia and Romagna. 1860 brought a change in the European political orientation thanks to the position of France and England in favour of annexation, and with this in mind on 11 March electoral voting began in the province of Modena where citizens were called upon to choose between ‘Union to the constitutional monarchy of King Vittorio Emanuele II’ and ‘Separate Kingdom’, the majority voting for annexation to Piedmont. In Turin, on 18 March 1860, Farini delivered the result of the vote into the hands of the King, who signed the same day the decree of annexation of the territories that became part of the Sardinian State. On 4 May, the King, together with Cavour and Farini, visited Modena and during his two-day stay he appeared at the balcony of the former Ducal Palace, warmly welcomed by the citizens.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Gli Estensi. A thousand years of history” Luciano Chiappini, Ferrara, Corbo Editori, 2001

“Gli Estensi. The court of Modena” edited by Mauro Bini, Il Bulino art editions

“Modena Capitale” Luigi Amorth, Banca Popolare dell’Emilia Romagna, Poligrafico Artioli SpA, 1997

Treccani Bibliographical Dictionary of Italians

“Il quinto Francesco”: the drama of a sovereign forced into exile, the tragedy of a family overwhelmed by war”, article in “Prima Pagina” 4 January 2015

“The forgotten duchess: Adelgonda of Bavaria on the centenary of her death”, article in “Prima Pagina” 23 March 2014