Isabella d’Este, eldest daughter of Duke Ercole I, was undoubtedly one of the most influential women of the Renaissance, famous both for her political skills, traces of which remain in her copious correspondence with the most important personalities of the time, and for her passion for collecting works of art. Married to Francesco II Gonzaga, it was thanks to Isabella’s diplomatic skills that the Marquisate of Mantua was elevated to a Duchy by Emperor Charles V. While of her artistic passions, the fabulous Studiolo – she was the first woman to have a private space for her own artistic and cultural interests – and the Grotta, in which it housed the most illustrious works of the artists of the time, from Mantegna to Perugino, and where an extraordinary collection of antiquities was on display.

The Life: education and marriage

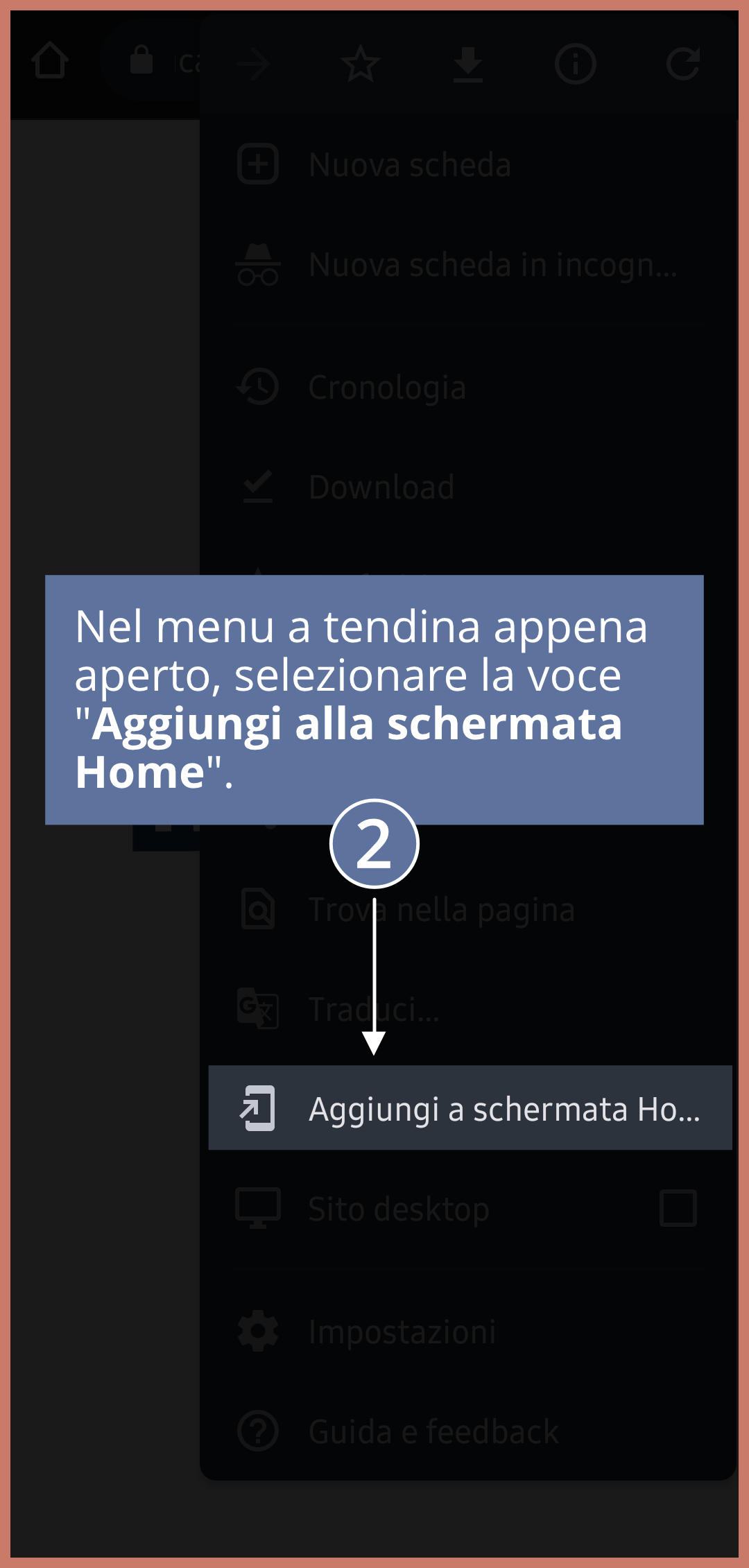

The eldest daughter of Duke Ercole I d’Este and Eleonora of Aragona, Isabella d’Este was born on 17 May 1474. Despite the fact that she was not a boy, a primary requirement in the line of succession of the Duchy, the Duke’s first daughter was greeted with joy because she arrived after two unsuccessful pregnancies.

Even outside of the family context, her figure soon won and garnered admiration, consigning her to history as one of the central characters of the Renaissance: patron, collector and grand dame, but above all very skilled in politics, capable of weaving relationships and bonds capable of protecting her own territories, so much so that Niccolò da Correggio described her as ‘the first woman in the world’.

Isabella had received an education of the highest level since childhood, from Latin to singing and dancing, without neglecting the study of musical instruments. But it was the unique opportunity, precisely because she was the first-born child, to frequent princes, ambassadors and all the great personalities passing through Ferrara, that allowed her to learn from an early age the rules of court and how to treat the most important guests with ease: this experience was of fundamental importance to her in future political and diplomatic negotiations.

The first political agreement saw her at the age of only six, when, in order to strengthen alliances between families, she was betrothed to Francesco II Gonzaga, who was fourteen years old at the time. Only a few days after the official engagement, the Duchess of Milan asked her to marry her son Ludovico Sforza, known as the Moro. Because of his engagement to the Gonzagas, the Moro was granted the hand of his second daughter, Beatrice, but the thought of this missed opportunity, the idea of a prestigious destiny at the Milanese court had fascinated Isabella, who instead had to be content with a Marquisate: the sense of rivalry towards her younger sister that characterised their relationship throughout their lives can be traced back to this.

The wedding with Gonzaga was celebrated, as planned, in the ducal chapel in Ferrara on 12 February 1490, but without the presence of the groom, as was often the case at the time. The following day, the wedding procession began its journey to Mantua, crossed a festive Ferrara and then, having arrived on the banks of the Po, Isabella embarked on the bucintoro, bidding farewell to her homeland. The journey lasted three days and it was not until 15 February that Isabella crossed the threshold of her new city to finally meet Francesco Gonzaga, who was waiting for her accompanied by a retinue of ambassadors, knights and gentlemen. The whole city of Mantua celebratedand at the time it was estimated that the foreign guests invited numbered almost 17,000. Moreover, this wedding is remembered as one of the most important of the time: eight days of festivities, until the end of the carnival, with banquets, tournaments, jousting, shows, canteens, and it is said that on those days even the fountains dispensed wine instead of water.

Isabella was immediately appreciated for her gifts as a great lady of the court, forging a strong bond right from those first moments with her sister-in-law Elisabetta, wife of the Duke of Urbino, with whom she maintained a copious correspondence throughout her life.

The marriage brought the couple as many as six children, and it seems that Isabella herself, despite her personal history, never managed to become attached to her daughters. It was not until 17 May 1500 that the long-awaited son, Frederico, was born. The difference in attitude was immediately apparent: for him Isabella used the precious painted cradle given to her by her father for the first time, which she had never wanted to use for her daughters.

A passion for the arts

The years at the Gonzaga court were filled with travel and embassies and, in addition to her family, Isabella devoted herself to her great passions: art and theatre. It is no coincidence that she was the first woman to own her own Studiolo, a space reserved for her cultural and intellectual interests that every guest passing through Mantua aspired to visit to see the wealth of her art collection, including the paintings by Mantegna, Lorenzo Costa and Pietro Perugino that occupied its walls. Isabella took care of the Studiolo all her life: it was the first room she took care of upon her arrival at the palace and, in 1498, when the space became too small to hold all the works she was collecting, she began construction of the Grotta: a room below the Studiolo, characterised by a large barrel vault, to house the rich collection of marbles, sculptures and Greek antiquities. There was no illustrious guest or art lover who did not want to visit these splendid rooms, which also housed gems, coins, inlay work, bas-reliefs, vases and cameos.

At the time of his arrival at the Mantuan court, the official painter was Andrea Mantegna, with whom relations broke down almost immediately. The cause was a portrait of the painter that Isabella disliked so much that she never wanted to be represented by Mantegna again. Isabella wanted to give an image of herself that corresponded to courtly standards, and for this she turned to other court painters. Belonging to the Gonzaga family in fact gave her the opportunity to get to know great artists: among them Gian Cristoforo Romano, sculptor, goldsmith and medalist, who had already worked for his sister Beatrice d’Este first at the Estense court and then at the Milanese court. Evidence of this relationship can be found in the preparatory terracotta bust (now in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA,) and in a gold medal with the effigy of Isabella decorated with diamonds and enamels (now in the Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna).

In Mantua she also met Leonardo da Vinci: Isabella did not miss the opportunity to have her portrait painted, when the artist, in the early 16th century, fleeing from the French who had conquered Milan, found refuge at the court of the Gonzaga. It was on this occasion that Leonardo made two sketches of Isabella’s portrait, one of which has fortunately survived to the present day, and is now in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (five copies are currently known, one of which is kept in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi in Florence). With insistence, Isabella tried to convince Leonardo to continue the drawing on cardboard, completing the painting, but the painter’s commitments made it impossible to comply with the Marquise’s request.

Isabella’s passion for theatre originated at the Estense court in Ferrara, where theatrical performances were fashionable and frequent. Isabella succeeded, with tenacity and will, in bringing various performances to Mantua: the first might be the comedy ‘Captivi’ by Plautus, in 1496. Isabella’s extraordinary commitment to promoting the theatre brought her direct competition with the court of Ferrara in the following years.

Lastly, Isabella maintained an assiduous correspondence with Ludovico Ariosto and their mutual esteem led the poet, as early as 1507, to illustrate the contents of his ‘Orlando Furioso’ to the lady and personally deliver the first edition of 1516 to her.

Politics and diplomacy

In 1501 Alfonso, Isabella’s brother and future Duke of Ferrara, married Lucrezia Borgia, daughter of Pope Alexander VI and on her third marriage. The Marquise, as eldest daughter and eldest sister of Alfonso, was obliged to do the honours and receive the bride in her hometown. The rivalry between the two noblewomen is well known: the meeting in Ferrara was preceded by espionage actions (to obtain information on clothes, jewellery and habits) of which the chronicles of those days leave us with numerous anecdotes. Hostilities came to a climax with the probable love affair between Isabella’s husband and Lucrezia, which was rumoured in their respective courts.

The events of Mantua and Ferrara were however destined to intertwine again: in 1509 the cities both joined the League of Cambrai led by Pope Julius II, who together with Ferdinando II of Aragona (King of Naples and King of Sicily), Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg (Holy Roman Emperor), Louis XII (King of France and Duke of Orleans) and Charles II (Duke of Savoy) allied themselves against the expansionist aims of Venice. Unfortunately, on 8 August 1509, Francesco Gonzaga was captured by the Venetians and dragged off to prison, where he would remain for almost a year. Isabella, upon hearing the terrible news, immediately mobilised for his release and demonstrated her political skills by firmly governing the state for which she was responsible in the absence of her husband. In June 1510, after innumerable negotiations and also thanks to the diplomatic intervention of Julius II, Francesco was freed, but as a pledge of loyalty to the Papal State, he was sent to Rome as a ‘guest’, or rather hostage, of the Pontiff, the little 10-year-old Federico Gonzaga, who would only return home in 1513.

When her husband died in 1519, Isabella was called upon to govern the Marquisate of Mantua as regent for her 18-year-old son Federico, once again proving her diplomatic and political skills and abilities. After her son’s rise to power, Isabella moved to the Corte Vecchia, and her first thought was to recreate in her new residence the rooms she loved most: the Studiolo and the Grotta (1520-1522).

Isabella, now out of court politics, continued to weave correspondence with sovereigns, cardinals, artists and men of letters, spending her time travelling in search of the precious objects she continued to collect. It was precisely these passions of hers that placed Isabella in the Eternal City during the Sack of Rome on 6 May 1527. In those agitated moments, surely fearing for her own life as well, her greatest concern was for the fate of her three sons who, at that moment, were on three different fronts: Federico was an ally of the Pope, Ercole had just received the cardinal’s biretta, while Ferrante was militating among the Spanish forces. Isabella found refuge in Palazzo Colonna, which was spared from the terrible assaults of the Lansquenets, and here she gave shelter to about 2,500 people: the story goes that she did not leave Rome until she was sure that everyone was safe. It is not certain whether the episode was made known to Charles V, who had indeed ordered the descent of the Lansquenets into Rome, but who had to distance himself from their violent acts. The detail would not be unimportant because the Habsburg had meanwhile been crowned King of Italy and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in Bologna; Isabella was also present at the ceremony. With the new investiture, Charles V decided in 1530 to elevate Federico from Marquis to the first Duke of Mantua. A success that was also achieved thanks to the skilful diplomatic manoeuvres of Isabella, who, despite being cut off from the affairs of state by her own son, continued to weave relations with the most influential personalities of the time, in order to consolidate and increase the power of the court of Mantua. The letters Isabella wrote during the course of her life number around 15,500 and this intense activity characterised her entire existence.

In 1538, she spent the carnival in her hometown and, although fatigued, she wanted to go to Venice to purchase more precious objects, returning to Mantua only in November in poor physical condition. Isabella continued to engage in correspondence until the last weeks of her life, until one evening in February 1539, at the age of 64, when she called her closest loved ones around her for a final embrace and passed away. She is buried in the Church of Santa Paola in Mantua.

Isabella’s Studiolo

As mentioned, Isabella was the first woman to own a space all to herself dedicated to studying, reading and preserving the art objects she was collecting over time.

The first setting up of the Studiolo took place in the north-eastern tower of the Castello di San Giorgio, where Isabella lived and devoted herself to this project with passion and energy, initially also to combat the boredom of a husband who was always away and the sadness of having abandoned her hometown. After her husband’s death and her son Federico’s rise to power, her collections were moved to Corte Vecchia, today’s Ducal Palace in Mantua.

Here Isabella occupied two adjoining flats that form an ‘L’ plan: the Appartamento della Grotta consists of the Studiolo, the Grotta, other private rooms, camerini and finally the secret garden, while the Appartamento di Santa Croce has larger reception rooms. Between the Studiolo and the Grotta there is a portal made of polychrome marble of great value and decorated with plant motifs and figures, the work of the sculptor Cristoforo Romano, datable to the early 16th century.

Isabella conceived a sumptuous space here and saw to it personally, right from the choice of flooring, which fell on precious majolica tiles from Pesaro decorated with her mottos, as well as the symbols and coats of arms of the Gonzagas.

On the walls of the Studiolo was a cycle of paintings inspired by Platonic philosophy: allegories representing the triumph of virtue over passions, harmony and the victory of chaste love over carnal love. The works were personally commissioned by Isabella, between 1496 and 1530, from the most famous artists of the time: Andrea Mantegna, ‘The Parnassus’ and ‘Minerva banishes the Vices from the Garden of Virtues’; Perugino, ‘Battle between Love and Chastity’; Lorenzo Costa, ‘Isabella d’Este in the Kingdom of Harmony’ and ‘The Kingdom of the God Como’; Correggio, ‘Allegory of Virtue’ and ‘Allegory of Vice’; the latter present a mirror-image composition indicated to be placed at the sides of an entrance, then commissioned for the new residence in Corte Vecchia. The paintings, although taking different directions, are today all on display at the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

A work by Giovanni Bellini was also supposed to be part of this cycle. It is ‘Il Festino degli Dei’ (The Feast of the Gods), which, however, was later acquired by Duke Alfonso I for his own ‘Alabaster Camerino’. The work is preserved in the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Today the space of the Studiolo appears empty, no traces remain of the objects listed three years after Isabella’s death by the notary Odoardo Stivini. To give the visitor an idea of the exceptional nature of this place, there remain in the Studiolo the wooden ceiling characterised by refined carvings and the alternation of blue and gold (repositioned here in 1933), and in the Grotta the carved boiserie with decorations of musical instruments and architecture.

It is unmistakably Isabella’s space: not only is her name, or more simply her monogram, engraved in several places, but this space expresses and emphasises her humanistic education, her personality and her utopia of a joyful world governed by the Virtues.

The name of the Marquise and her emblems are thus visible in many places: for example, on the windows it is still possible to read “Isabella Estensis” (and not Gonzaga); the same inscription appears carved above the columns of the garden; furthermore, carved into the woodwork is perhaps the motto dearest to the Marquise “NEC SPE NEC METV” meaning ‘without hope, without fear’, which induces one to continue living, in life as in the politics of the State, without fear and with firmness.

The Grotta has a beautiful vault decorated with gilded stuccoes and carvings, with another emblem dear to Isabella in the centre: a pentagram without notes, but only with signs suspending the sound, signifying that in life more important than content are the moments of pause. Archaeological objects such as coins, cameos, antiquities and bronzes were exhibited here; from here one can access a private garden where one could listen to concerts and readings.

Curiosity about Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria”

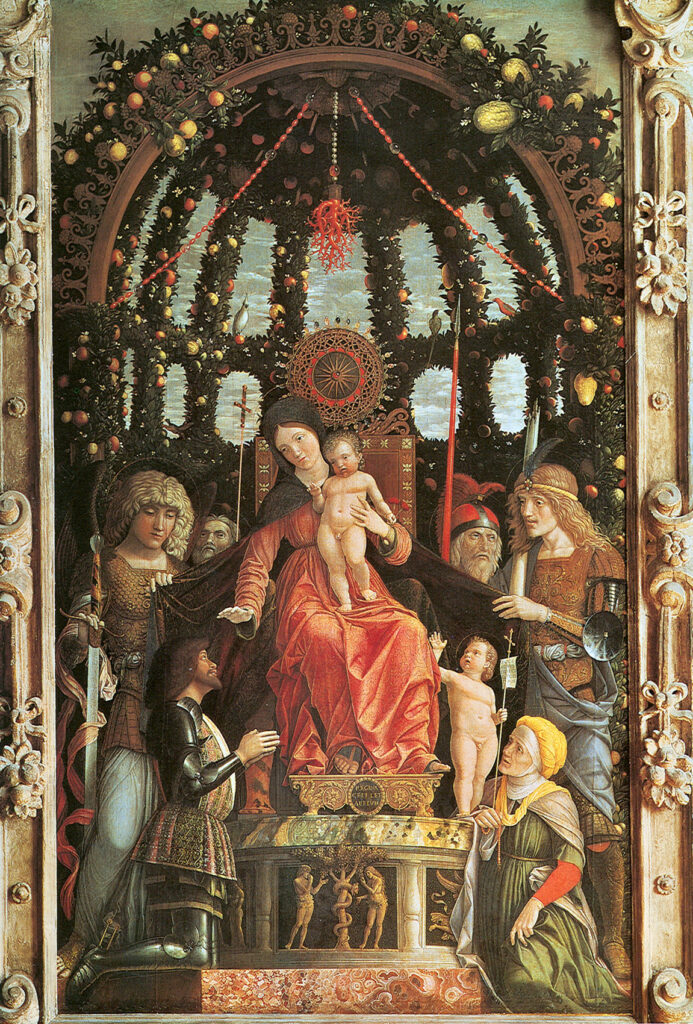

Relations between Isabella and the painter Andrea Mantegna were stormy, as mentioned above, but this did not prevent the Marchioness from commissioning a masterpiece from him in 1496, the ‘Madonna della Vittoria’.

Two events, apparently distant from each other, are recalled behind the creation of this work, which are related thanks to Isabella’s skilful moves. The first episode is linked to the Battle of Fornovo and Francesco Gonzaga. Isabella sent her husband, engaged in battle, a cross and a relic, asking him to entrust himself to the Madonna for protection, vowing to build a monument to the Virgin upon his return. The second event took place in Mantua, where Isabella administered the state in the absence of her husband. At that time, a Mantuan Jew bought a house for his family and on one of the outside walls there was a tabernacle with an image of the Virgin Mary, which, once the sum due to the bishop had been paid, the Jew was allowed to remove. During the feast of the Ascension, however, the people became aware of this lack and only thanks to the intervention of the soldiers sent by Isabella, was the looting of the house and the lynching of the Jew prevented.

Isabella therefore showed her diplomatic skills and that of a skilful strategist, combining the two events: to calm the people she ordered the Jew to pay Mantegna the commission to paint an altarpiece with the image of the Virgin, celebrating the victory at Fornovo, thus also fulfilling the vow made by her husband in battle. The altarpiece, now on display in the Louvre, is one of the painter’s most important works, but due to previous arguments between the two, Isabella did not want to be portrayed next to her husband, who was kneeling in the foreground in his great captain’s armour. The work aroused so much admiration that the Jew was obliged to build a chapel to house it on the ground where his house was to be built.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Lorenzo Bonoldi “Isabella d’Este La Signora del Rinascimento”, Guaraldi Engramma, 2015

Jérémie Koering. Isabelle d’Este collectionneuse et commanditaire. Perspective – la revue de l’INHA: actualités de la recherche en histoire de l’art, Institut national d’histoire de l’art / A. Colin, 2006 (2), pp.319-324.

Leandro Ozzola “Isabella d’Este and Titian” in Bollettino dell’Arte pp 491-494 1931 – XI (MAY, YEAR X) http://www.bollettinodarte.beniculturali.it/opencms/export/bollettinoarteit/sitobollettinoarteit/contributi/editoria/bollettinoarte/fascicoli/fascicoli-serie-ii/visualizza_asset.html_1598946986.html

Clinio Cottafavi “Palazzo Ducale di Mantova – I gabinetti di Isabella d’Este – Vicende, discussioni, restauri” in Bollettino dell’Arte pp 228-240, 1934 – V (Novembre, ANNO XXVIII) http://www.bollettinodarte.beniculturali.it/opencms/multimedia/BollettinoArteIt/documents/1438091533718_08_-_Cottafavi_228.pdf

Sara Accorsi “Le donne estensi: donne e cavalieri, amori, armi e seduzioni” Cirelli & Zanirato, Ferrara 2007 “Donne di potere nel Rinascimento” edited by Letizia Arcangeli and Susanna Peyronel, Viella, Rome 2008 Alessandra Necci “Isabella e Lucrezia, le due cognate: donne di potere e di corte nell’Italia del Rinascimento”, Venice: Marsilio, 2017

PhD thesis by Matteo Basora “Tra le carte della Marchesa. Inventory of the letters of Isabella d’Este, with a textual and syntactic analysis” University of Macerata, Department of Humanistic Studies 2017

“Le Studiolo d’Isabelle d’Este” catalogue rédigé sous la direction de Sylvie Béguin … [et al.]; étude au Laboratoire de recherche des musées de France par Suzy Delbourgo et Lola Faillant Paris: Edition des Musées nationaux, 1975

http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/ works-art/schemes/MN020-00087/